India’s Oil Demand Drives CMB Tech Fleet Diversification

By Dimitri Rhodes Nov 7 (Reuters) – Belgian oil tanker company CMB Tech says it will focus on the fast growing market in India as it reported third quarter results...

As the 2010’s come to a close, we’re taking a look back at the maritime stories that kept us talking the most these last ten years.

For me, the Deepwater Horizon was one of those “I’ll never forget where was when I first heard” kind of events. I was sitting in my home office in San Luis Obispo, probably contemplating how the heck to make gCaptain work, when I got a call from a maritime lawyer friend of ours telling me to check out the forum. When I logged on, I saw the post: “The Deepwater Horizon is on fire and the flames are 200’ tall. All personnel have abandon ship.” Many of you probably don’t realize this, but that was actually the first public reporting of the events that unfolded that night.

The next morning I woke up to the headlines (and conflicting reporting regarding the fate of those on board). The rest is history. After the blowout, the Deepwater Horizon sank, eleven people were killed, and what resulted was the largest offshore oil spill in American history (along with a 6-month deepwater drilling moratorium), the effects of which are still being felt to this day.

When the 2010’s began, piracy off the coast of Somalia and Indian Ocean was just hitting its peak. During the 2010-2011 timeframe, a merchant ship was attacked by Somali pirates once every other day on average, and pirates held for ransom dozens of vessels and hundreds of seafarers at any given time. One report estimated the cost of Somali piracy at its peak to be $7 billion annually, the vast majority of which was paid for by the shipping industry to help protect its vessels. In 2011 alone, some 31 ransoms were paid to Somali pirates, totaling around $160 million, the report claimed.

But thanks to a host of counter-piracy efforts, such as the increased use of private armed security guards, international naval coalitions, and improving conditions ashore, the number piracy incidents around the Horn of Africa began to decline and, by 2013, successful hijackings all but fell to zero. While incidents of Somali piracy are rarely recorded these days, experts continue to warn that the threat of piracy persists in the region and seafarers should continue to take extra precautions when traversing the area. Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, on the other hand, that continues to be whole other story…

The Costa Concordia cruise liner, with more than 4,200 passengers and crew on board, ran aground and partially sank on January 13, 2012, on the small Italian island of Giglio, tragically resulting in the deaths of 32 passengers. What makes the Costa Concordia a top post of the decade is not only the initial shock of the incident, but the record-setting salvage that followed.

Nearly two years after the ship wrecked, millions of people across the globe were glued to their televisions to watch the live “parbuckling” event, which was the operation to right the ship. At that point it was uncertain if the Costa Concordia would simply collapse under its own weight when moved, but it didn’t and the still-intact Costa Concordia was eventually refloated and towed to Genoa in July 2014, where it was slowly dismantled. The salvage has become known as the largest and most complex maritime salvage ever in history with a cost estimated at more than $800 million.

As for Francesco Schettino, Costa Concordia’s disgraced captain, he was later convicted and is currently serving a 16-year prison term for his role in the wreck.

We conclude the 2010’s staring down the barrel of the International Maritime Organization’s 2020 sulphur cap, marking a monumental shift in the fuel used by the world’s merchant ships. Under the new rules, beginning January 1, 2020, all ships trading internationally will be required to use marine fuel with a maximum sulphur content of just 0.5%, down from 3.5% currently, or be equipped with exhaust gas cleaning systems, aka scrubbers. The IMO says that limiting the sulphur emissions from ships will not only help improve air quality and help the environment, but will lead to tangible results by significantly reducing the number of premature deaths worldwide.

While IMO regulations to reduce sulphur emissions from ships predates the 2010’s, the tightening of sulphur regulations really picked up pace when regulations to reduce sulphur oxide emissions entered into force in 2010, introducing a new global sulphur limit and more stringent restrictions in designated emission control areas (ECAs). In 2012, the current 3.5% sulphur limit was established, followed by the establishment of the 0.1% limit for ships operating in designated ECAs in 2015. But it wasn’t until 2016 that the IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC 70) decided that the 0.5% limit would be imposed from 2020, not 2025 as some had hoped, and the scramble to establish refining capacity and secure 2020-compliant fuel, or some other form of compliance, has been on ever since.

Looking ahead, if the past decade has been about reducing airborne pollution for the benefit of human health, the next ten years will be defined by shipping’s decarbonization efforts. In April 2018, the IMO MEPC adopted an initial strategy for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from ships, signifying the IMO’s plan for concrete action to reduce shipping’s contribution to global climate change. The initial strategy, which is set to be finalized in 2023, envisions reducing the total annual GHG emissions from shipping by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels, as well as phasing out fossil fuels entirely by the end of the century. To be sure, this next challenge is a tall order for an industry that is famously slow to adapt to new norms and is also heavily reliant on fossil fuels, but it might not have any other choice.

A big challenge for the next decade will be identifying which technologies, and fuels, will help the shipping industry achieve its goals.

If the 2000’s were known for the first deliveries of so-called “megaships”, the 2010’s will officially be known for the megaships arms race.

With the arrival of Maersk’s first-generation Triple-E’s in 2013, 18,000 TEU capacity replaced 11,000 TEU as the benchmark of the world’s biggest containerships as carriers sought greater efficiency and economies of scale, especially on the key Asia-Europe trade. These days, just about every major ocean carrier operates at least some Ultra Large Container Vessels (ULCVs), and 20,000+ TEU capacity vessels are not uncommon. Rumor has it, a 25,000 TEU ship is even under development in China.

The 2015 sinking of the El Faro was the United States’ worst maritime disaster in decades. On September 29, 2015, the 790-foot steam-powered cargo ship departed Jacksonville, Florida for its regular service to San Juan, Puerto Rico. But for reasons we’ll never fully understand, it’s captain, equipped with outdated weather forecasts, ignored concerns of his crew and sailed directly into the path of Hurricane Joaquin, resulting in the ship foundering in more than 15,000 feet of water near the Bahamas. All 33 people on board perished.

The NTSB’s 26-month long investigation into the disaster found that the Captain’s decisions and TOTE’s poor oversight and inadequate safety management system led to the sinking. In its final report, the NTSB identified a multitude of safety issues and made over 50 recommendations to everyone from the U.S. Coast Guard, the FCC and NOAA, to organizations such as the American Bureau of Shipping and TOTE Services.

When oil prices began to crash in mid-2014, optimists hoped decline would be just a minor speed bump after years of recovery from the 2008 global financial crisis. Now, more than five years later, we are yet to see oil prices return to the $100 per barrel range.

What has resulted is perhaps the worst oil market glut in recent history, prompting bankruptcies, restructurings, mergers and acquisitions, and an overall recalculation of how to actually make money in the oil and gas E&P sector. Even now, there seems to be no end in the adapt for the prolonged downturn that has hit the global offshore industry, and just about every business that services it, especially hard.

Whether reporting on construction progress or setbacks, quarreling tugboat captains, or its far-reaching impact on global trade, the Panama Canal Expansion kept us talking these last ten years.

After a decade in the works, the more than $5 billion expanded project was the largest improvement project in the 100+ year history of the Panama Canal and fundamentally changed how the it is operated. By increasing the size of ships capable of using the waterway, the widening of Panama Canal could effectively doubled the capacity of the waterway and opened up new global trade routes. Since its inauguration in June 2016, the Panama Canal Expansion has lived up to the hype, consistently setting new cargo records and redrawing global trade maps, most notably in the liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector, which was previously prohibited from using the canal.

Ten years ago, nobody could imagine that in 2018, the United States would become a net oil exporter (albeit briefly) for first time since the 1950’s. The U.S. Energy Information Administration projects that in 2020, the United States will export more energy than it imports as increases in crude oil and natural gas production outpace growth in U.S. energy consumption. The shift will mark a new era of energy independence for the United States.

What prompted this shift was the lifting of the 40-year-old ban on U.S. crude exports at the end of 2015 and the U.S. shale revolution that, combined with LNG exports from the Lower 48 states, has propelled the United States to a leading global oil and gas producer, redrawing the world’s energy map in the process.

In 2014, the International Maritime Organization adopted the historic International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters, or Polar Code for short, establishing for the first time a mandatory set of rules covering “the full range of design, construction, equipment, operational, training, search and rescue, and environmental protection measures” specific to ships operating in harsh Arctic and Antarctic waters.

With its entry into force in 2017, the Polar Code highlights the increased maritime traffic in the polar regions, particularly in the Arctic where shrinking sea ice has opened new routes and extended the summer shipping season. The two most famous routes, the Northwest Passage through Canada and the Northern Sea Route (NSR) along Russia‘s northern coast, are favored because of the significantly shorter transit times between Asia, Europe, and North America.

Russia, however, is perhaps most interested in Arctic because of its potential to boost energy exports from its northern Siberian oil and gas fields. In late 2017, Russia began year-round shipments of LNG from the Yamal LNG project using a fleet of icebreaking tankers capable of operating across the entire length of NSR without icebreaker escort.

But while Russia has welcomed the possibility of increased Arctic shipping, many major shipping lines have pledged to not use the Arctic routes citing increased environmental risks, despite the competitive advantages that the route offers. With a warming arctic, longer shipping seasons, and more capable vessels, only time will tell if those pledges hold water. Russia’s state-run Rosatom, as operator of the NSR, estimates shipping along the route will increase more than four-fold by 2024 compared to 2018 levels, when nearly than 19 million metric tons of cargo passed through the route. Developing the NSR as a viable option for trade will not come cheaply, though, as Russia says it will take more than $11 billion in investments to make the route safe and viable.

Hanjin Shipping ranked as the seventh largest container line when it filed for court receivership in August 2016, leaving its fleet of ships and hundreds of thousands of containers stranded at sea and in ports across the globe.

For container shipping, 2016 was a particularly bad year with severe overcapacity and historically low freight rates plaguing the sector. The head of Hong Kong-based Seaspan once equated Hanjin’s demise to the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers at the peak of the global financial crisis. Like Lehman Brothers, the bankruptcy of Hanjin sent shockwaves across the transport and logistics sector and provided the realization that nobody, not even the world’s biggest carriers, were too big to fail.

Since Hanjin’s collapse, however, the container shipping industry has undergone some serious consolidation, including the establishment of major shipping alliances, or vessel sharing agreements that allow previously-competing shipping lines to pool their vessels, terminals and networks. An International Transport Forum report released earlier this year showed that in 2018, global shipping alliances emerged as the dominant feature of container shipping, with the three major alliances operating around 95% of the total ship capacity on the key East-West trade lanes.

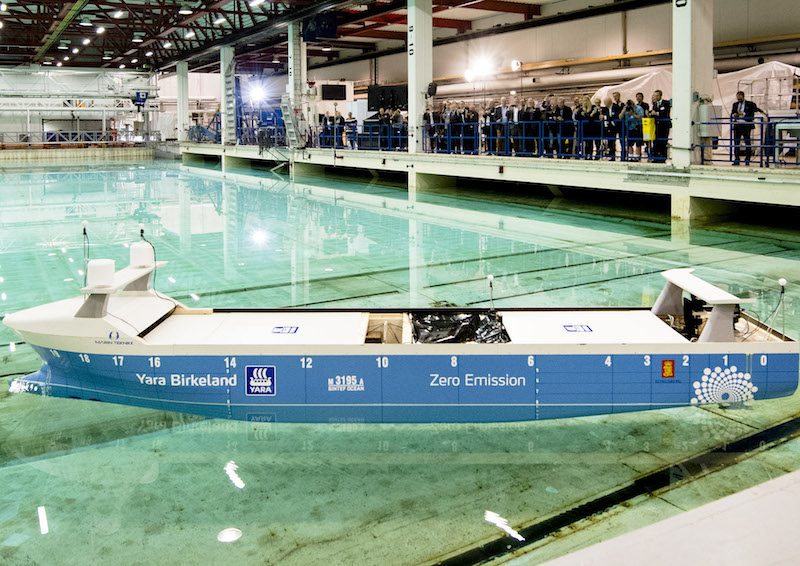

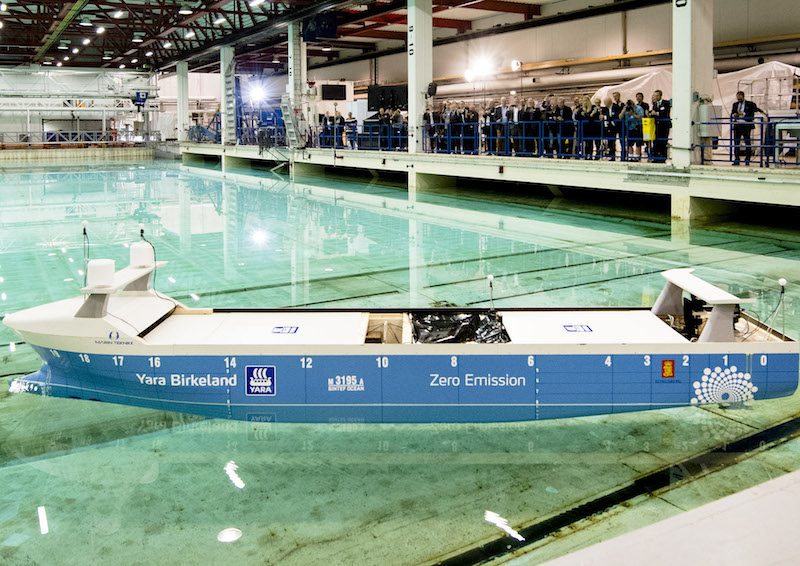

With the rise of artificial intelligence technology and greater connectivity at sea, the 2010’s will be looked back on as the decade when autonomous and semi-autonomous shipping really began to take shape, especially during these last few years.

In 2017, the IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee succumbed to pressure and decided to include the issue of autonomous ships on its agenda, recognizing the need for the IMO to take a lead role on the issue because of the rapid technological developments in the area of “Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS).”

A major milestone came earlier this year when the IMO MSC approved interim guidelines for autonomous ship trials, marking the IMO’s first concrete action addressing the issue. As for the legal challenges, the IMO is now in the middle of a “regulatory scoping exercise” which will touch on an extensive range of key items, including the human element, safety, security, liability and compensation for damage, interactions with ports, pilotage, incident response, and environmental protection.

While the first fully autonomously-operated ocean-going ships are still a long way away, the more likely scenario is that AI technology and cost-reducing automation will continue to be gradually incorporated into ships’ systems, and most agree that the initial impact of full or semi-full autonomy will be most profound in the short sea sector on fixed routes. But as for fully-autonomous, unmanned ocean-going ships? I’ll borrow a quote from Maersk’s CEO, Soren Skou: “Not in my lifetime”.

After a decade of planning, China in October green-lit the merger of its two largest state-owned shipbuilding groups, China State Shipbuilding Corp and the China Shipbuilding Industry Co. The merger capped a decades-worth of consolidation among inefficient, money losing state-owned entities which has catapulted China to the forefront of international shipping powerhouses and the world’s leading builder of commercial ships.

In 2017, the merger of its two biggest shipping lines, COSCO and China Shipping, created China COSCO Shipping, parent to what is now the world’s third largest container line, along with other globally-competitive units spanning oil and gas shipping, dry bulk, ship finance, and international terminals.

China has also spent the last decade beefing up its military, and its Navy in particular. For more on that, we turn to Dr. Sal Mercogliano, gCaptain contributor and associate professor of History at Campbell University in North Carolina, where he teaches courses in World Maritime History and Maritime Security:

“The dawn of 2010 found elements of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) on an overseas deployment to protect its foreign commerce in the Gulf of Aden. Named for the commander of the last foreign expedition, over six centuries earlier, Operation Zheng He demonstrated to the world the capabilities of the new Chinese Navy. As part of their One Belt, One Road Policy, China aims to secure its key trade routes, in particular the import of raw materials from Africa and the Middle East, and the export of goods to Europe. A major component of this initiative is the development of bases on newly created islands in the South China Sea, claimed by China as part of its territorial waters under the Nine-Dash Line. China has increased the production of warships, introducing its first aircraft carrier Liaoning in 2011 (bought from Ukraine as an uncompleted Soviet carrier) and its first domestically built version, Shandong in 2019. China emerges from the second decade of the twenty-first century as the fastest rising naval power, a rival to the United States in the western Pacific, and the largest builder of commercial ships in the world.”

With that, we end this decade’s wrap-up of the top maritime stories that shaped the decade. Do you have something to added to the list? What will be the top maritime stories of the 2020s? Shoot me an email or comment on social media.

Happy New Year!

This story was originally published Friday, December 27, 2019.

Join the gCaptain Club for curated content, insider opinions, and vibrant community discussions.

Join the 109,890 members that receive our newsletter.

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Access exclusive insights, engage in vibrant discussions, and gain perspectives from our CEO.

Sign Up

Maritime and offshore news trusted by our 109,890 members delivered daily straight to your inbox.

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up