India Seeks $1.1 Billion Reparation After MSC Fuel Spill in May

The southern Indian state of Kerala has sued MSC Mediterranean Shipping Co. for the environmental damages caused by a ship capsizing off its coast, according to a court document.

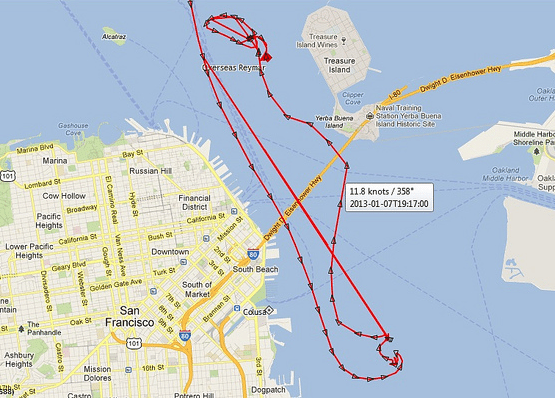

The damage to the 752-foot tanker Overseas Reymar following an allision with tower six of the San Francisco Bay Bridge, Monday, Jan. 7, 2013. U.S. Coast Guard photo

As the Coast Guard and the National Transportation Safety Board launch their investigation into Monday’s tanker allision with the San Francisco Bay Bridge, information available to the public has hinted that excessive speed coupled with poor visibility may have played a role.

But was speed really a factor in this case?

As we reported yesterday, the 752-foot Marshall Island’s-registered tanker Overseas Reymar allided with tower six of the Bay Bridge at approximately 11:20 a.m while under the command of a San Francisco Bar Pilot as it was exiting the Bay. Luckily, no reports of injuries or pollution resulted, but the incident has brought back memories of the M/V Cosco Busan which in 2007 struck the Bay Bridge and spilled thousands of gallons of fuel into San Francisco Bay.

In the Cosco Busan accident, the NTSB ultimately determined that a medically unfit pilot (John Cota failed to disclose a plethora of prescription drugs he was taking), an ineffective master, and poor communications between the two were primary causes of the accident. In all likelihood, the investigation into yesterday’s allision will have very different outcomes, but a number questions still arise.

According to AIS data from the time of yesterday’s incident, the Overseas Reymar was travelling at approximately 11.8 knots when it struck the bridge. Additional reports indicate that San Francisco Bay was under a thick blanket of its famous pea soup fog, with visibility down to about a quarter mile.

AIS data of a ship which just passed under the Bay Bridge tonight indicated it was traveling at 10.8 knots.

One might instantly jump to the conclusion that since the Overseas Reymar was traveling a knot faster under less visibility, that she was probably going too fast, however the armchair sailor making that conclusion is doing so without understanding that “safe speed” has many factors that have yet to be analyzed in this case.

The maneuvering characteristics of ships can, and do vary greatly depending on the type of engineering plant, the types of propellers, the number and types of rudder, the location of the wheelhouse, the visibility from the bridge, whether or not the ship is loaded with cargo, radar interference, harbor characteristics, and other factors.

The bottom line is that the analysis of what went wrong is going to take some time. Making assumptions by looking at a couple of ship tracks would likely not help draw accurate conclusions. Historical data of similar sized and loaded ships, in similar conditions, might however. We’ll follow the investigation as it gains more insight into the incident.

We should also mention that the NTSB has taken on the investigation, classifying it as a “major casualty” and says that they will be reviewing the circumstances of the accident in light of the safety recommendations made following the Cosco Busan accident. Those recommendations are below:

New Recommendations

As a result of the [COSCO BUSAN] investigation, the Safety Board made the following safety recommendations.

To the U.S. Coast Guard:

To Fleet Management Ltd.:

To the American Pilots’ Association:

– Mike Schuler, Edited by Rob Almeida

Sign up for gCaptain’s newsletter and never miss an update

Subscribe to gCaptain Daily and stay informed with the latest global maritime and offshore news

Stay informed with the latest maritime and offshore news, delivered daily straight to your inbox

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up