By Ari Natter (Bloomberg) Floridians reeling from widespread power outages and a deadly surge of water following Hurricane Ian are facing another problem: raw sewage swirling into the floodwaters.

Untold gallons of raw and poorly treated sewage have flowed into streets and rivers as floodwaters inundate infrastructure, power failures knock pumps offline, and manholes overflow.

Such discharges can carry bacteria like E. coli, parasites and viruses that can make humans sick. Nutrients contained in human waste such as phosphorous and nitrogen can also lead to red tides — concentrations of toxic algae — and blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) blooms in ocean waters, which can kill fish and other wildlife. Recent years have seen severe red tides off Florida’s Gulf Coast.

Officials have warned the public to avoid contact with standing water in the vicinity of discharges. Exposure to contaminants in floodwaters may cause skin rashes, gastrointestinal illness and other health problems, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

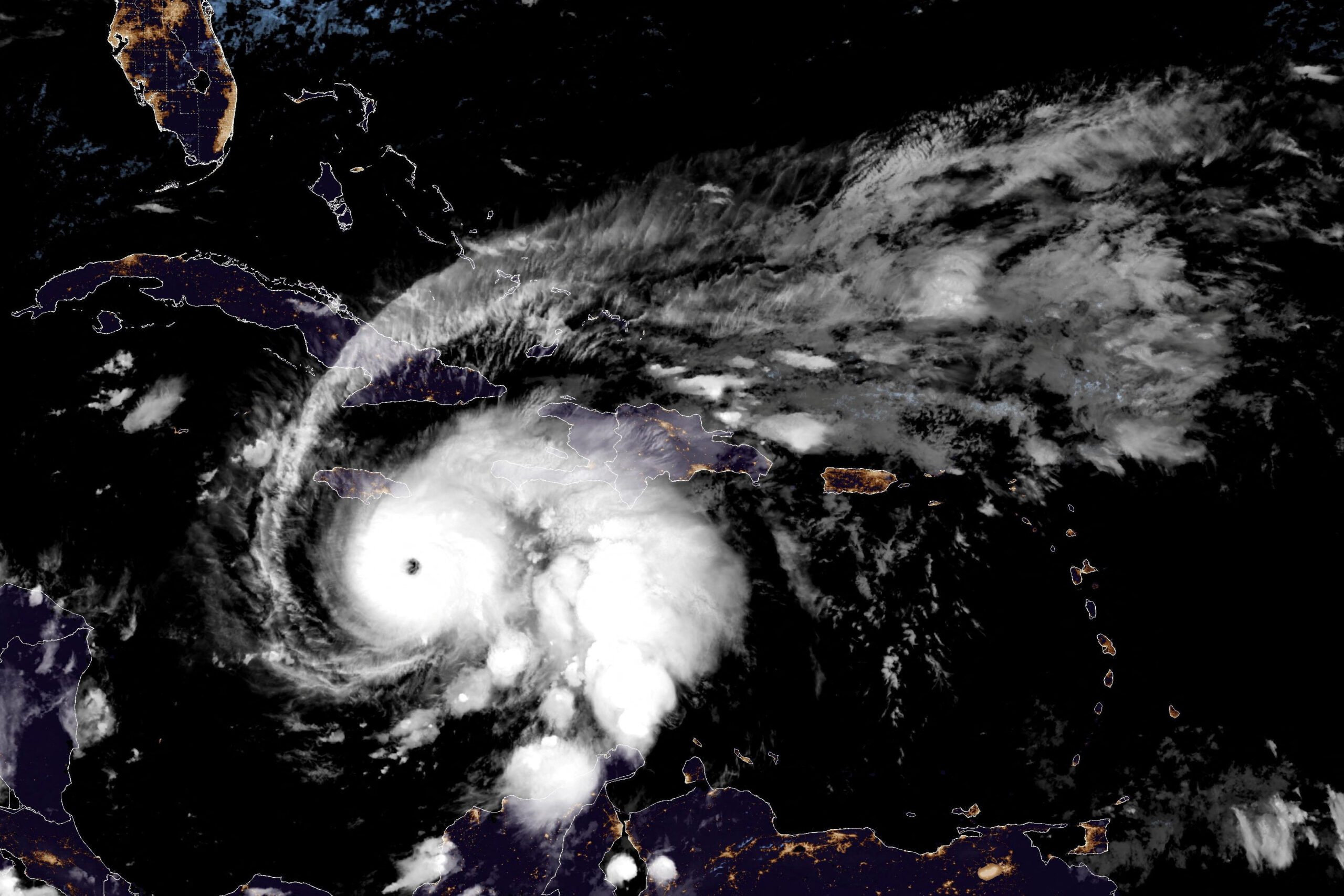

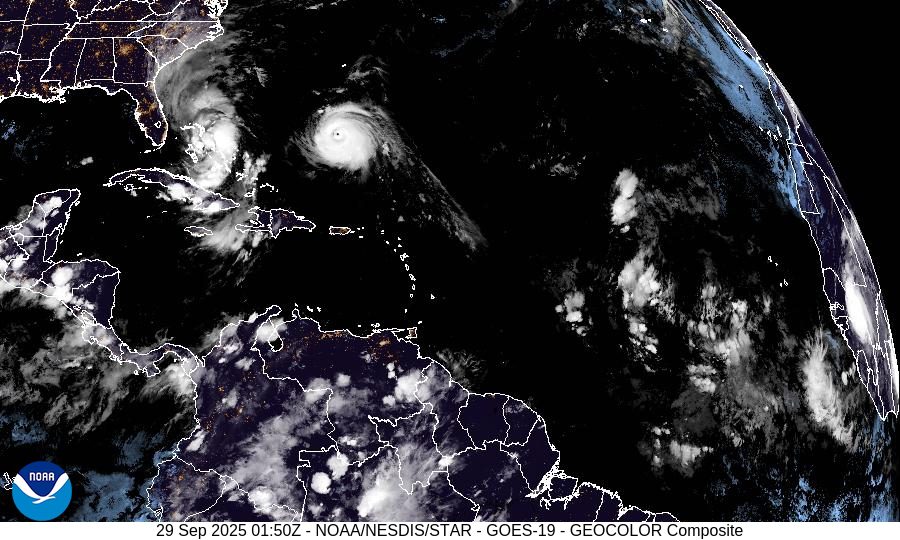

Ian slammed ashore in southwestern Florida as a Category 4 Hurricane, dumping nearly 20 inches of rain in some areas and cutting power to millions.

“Whether it’s the storm surge or just the vast amounts of rain, there is not a sewer system on the planet that can take that kind of hit without having some sort of overflow,” said Nathan Gardner-Andrews, chief advocacy officer for the National Association of Clean Water Agencies. “As storms get more intense you are going to see unfortunately more incidents where systems get overwhelmed.”

Unlike in other parts of the US where sewer systems can use gravity, Florida’s flat topography means a series of lifts and other infrastructure is needed to get wastewater where it needs to go. If those pumps fail or lose power, they overflow, Gardner-Andrews said.

On Thursday afternoon, after a water treatment facility in Bradenton become overwhelmed by stormwater and had to be bypassed, officials were expecting millions of gallons of wastewater to be released into the Manatee River, said William Waitt, the city’s superintendent said, adding the incident was ongoing.

In the Orlando suburb of Casselberry, overflowing tanks at a plant after heavy rains resulted in the discharge of tens of thousands of partially treated waste, said Dawn Swailes, the city’s water reclamation superintendent.

And Ian caused thousands of gallons of sewage to be discharged into a storm drain from an overflowing manhole in Miami, according to a filing with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, one of dozens of reports of sewage releases the agency received following the storm.

The state’s water and sewer infrastructure “is going to be heavily impacted by Ian,” Brock Long, who previously served as administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, said on Bloomberg Television. “Unfortunately for the citizens that reside down there, they’re going to have to change their mindset and expectations: The infrastructure’s just not going to work for a long time.”

Florida is no stranger to major sewer spills following hurricanes. Hurricane Irma in 2017 led to the discharge of millions of gallons of wastewater, according to a report from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. The release after Hurricanes Hermine and Matthew in 2016 was even bigger: 250 million gallons.

Part of the problem is that in some areas of the state, like Miami-Dade County and Fort Lauderdale, wastewater infrastructure is old and crumbling and allows torrents of excess groundwater and stormwater into the system, said Brian LaPointe, a research professor at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. In some places the pipes used to carry waste are made out of cast iron that corrodes, or even a kind of wood pulp known as Orangeburg, he said.

The US Environmental Protection Agency estimated in 2016 that $271 billion is needed to maintain and improve the nation’s wastewater pipes, treatment plants and associated infrastructure.

In addition to sewer overflows, the contents of some of Florida’s hundreds of thousands of septic tanks will contribute to the human waste flowing into the state’s Caloosahatchee River and eventually into the Gulf of Mexico, LaPointe said.

“I’d say this is going to be unprecedented,” LaPointe said in a phone interview. “We are anticipating seeing a number of these algal blooms in the wake of Hurricane Ian.”

One model the state could look to in the future is in the Florida Keys. Monroe County spent about $1 billion on a septic-to-sewer upgrade that included new, tightly sealed pipes to keep stormwater out and an advanced wastewater treatment system to remove nitrogen, preventing algal blooms that damage coral reefs. The water is then injected more than 3,000 feet underground, LaPointe said. The area reported no sewage spills after Irma, despite being flooded, he added.

“This is really where I think Florida is going to be heading in the future,” LaPointe said. “We are going to have to spend billions of dollars in many of these urban areas.”

By Ari Natter © 2022 Bloomberg L.P.

Editorial Standards · Corrections · About gCaptain

This article contains reporting from Bloomberg, published under license.

Join The Club

Join The Club