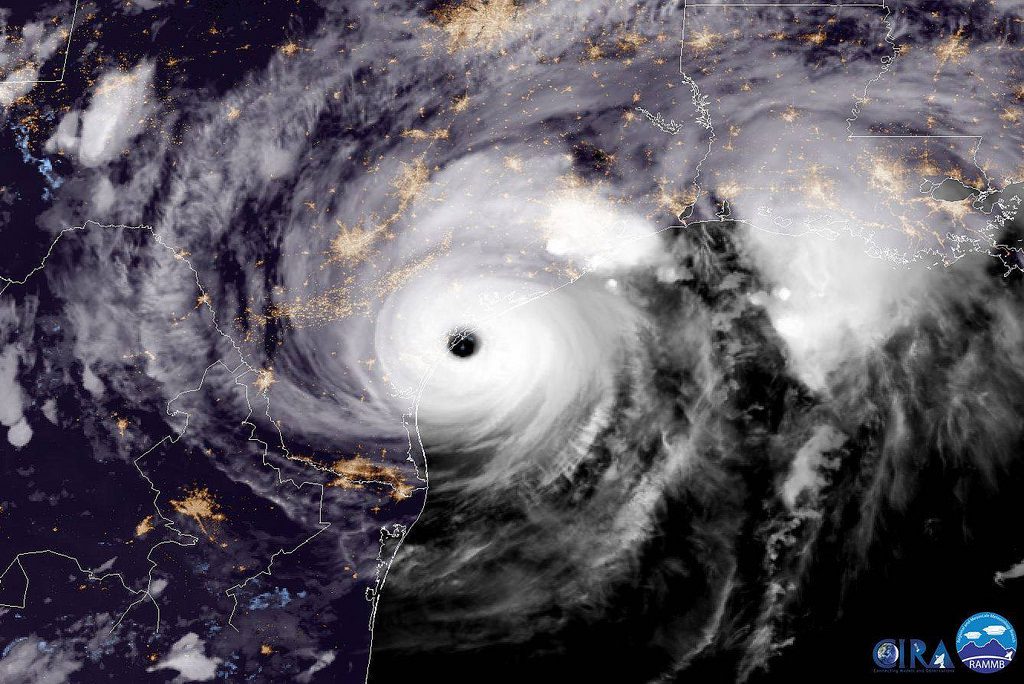

GOES-16 captured this geocolor imagery of Hurricane Harvey on the verge of making landfall on the Texas coast on August 25, 2017. Credit: CIRA

By Eric Roston (Bloomberg) — How powerful would Hurricane Harvey have been in 1880? How much stronger might it be in 2100?

A single Hurricane Harvey has been more than anyone can bear. But to better prepare cities for future storms, researchers are preparing to re-watch Harvey thousands of times. They’ve already been studying earlier storms, and their conclusions don’t bode well for the decades to come.

In the months and years after Superstorm Sandy’s 2012 assault on New Jersey and New York, Gary Lackmann, an atmospheric science professor at North Carolina State University, was asked how the event might be understood in light of human-driven global warming. He knew that the question everyone wants answered—did climate change cause the storm—wasn’t the right one. Hurricanes were around long before the industrial revolution. Two questions did, however, resonate:

How does climate change affect the frequency or intensity of huge storms? What would the weather pattern that sustained Sandy have spawned in a cooler past or a hotter future?

The first question is the more difficult one, though research has shown that the future will likely see more intense storms, even if there may be fewer overall. Asking the second question, however, might lead to useful conclusions about weather extremes, he felt. Lackmann spent the past several years gleaning insight from atmospheric research models of violent storms, such as Hurricane Floyd in 1999 and the flooding in the south-central U.S. in 2010, in an effort to answer question number two.

A 2015 paper, “Hurricane Sandy Before 1900 and After 2100,” looked at how warmer or cooler versions of the same large-scale weather pattern that carried Sandy would affect its intensity and path along the U.S. East Coast. Lackmann held everything constant except variables affected by temperature, including the sea, air, and land temperatures that influence humidity. In other words, how projected increases in global warming will affect storms decades from now, and how the warming thus far helps feed storms today. Sandy had many idiosyncrasies, notably including a square left-turn from its north-northeastern route in the Atlantic Ocean, smack into the East Coast. Lackmann found that the difference between an 1880 Sandy and the Sandy of 2012 was small compared with the gap between the 2012 version and a Sandy that arrived in 2100. The 19th century-simulations revealed a slightly weaker storm than the real-life one. The 1880 Sandy also made landfall about 60 miles south of where the actual 2012 storm hit, coming ashore near Atlantic City.

“The difference between the 1800s version and the present-day Sandy was not that significant,” Lackmann said.

That’s not true of the Sandy projected to strike in 2100. Given Lackmann’s assumptions, that storm would hit land about 120 miles farther to the north-northeast, around eastern Long Island or Connecticut. Along that simulated path, it grows significantly stronger than the 2012 Sandy, an observation that became clear early in the simulations.

Lackmann conducted his research using the mathematically simulated reality of computer models. First, he tested how well several general-circulation models were able to reproduce the storm once it passed a certain point (in this case, near the Bahamas). Satisfied that the simulations came close to the actual data, he re-created the large-scale weather features documented at the end of October 2012. He then turned down variables related to 20th century warming, to approximate conditions around 1880. He then re-ran 2012 conditions. Finally, through the same weather system, he ran the warming variables as projected into the future, which were developed for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

By simulating different heat-profiles over the same weather, he was able to produce estimates of an 1880 and a 2100 Sandy. The study doesn’t look at whether the storm would have formed under different conditions, only how warming may have affected its development, and path.

The biggest impact multiplier is human decisions on the ground

No two storms are identical, particularly Sandy and Harvey. “Sandy didn’t stall,” Lackmann notes. Nor did, for example, Hurricane Irene in 2011 or Matthew last year. Harvey’s destructive holding pattern in and around Houston has placed stalling storms front-of-mind for hurricane researchers. Whether there’s been a change in high-level wind patterns that “steer” storms is of paramount importance, according to Kerry Emanuel, atmospheric science professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

One challenge that Lackmann identified is pinpointing whether storms really are slowing down, and consequently dumping more water where people live. Hurricane Easy in September 1950 looped around Florida’s central Gulf Coast and dropped more than 45 inches of rain over the course of a week. Hurricane Flora poured 100 inches on Santiago de Cuba, in Cuba, in October 1963.

“These events have happened before,” Lackmann said. “It would be very difficult to say that Harvey stalled because of climate change. It would be difficult to ever truly sort that out.”

One way to attack this particular conundrum, though, might be to look at how quickly hurricanes and tropical storms have moved north over time, to see if their speed has slowed systematically.

The biggest impact multiplier in many storms won’t be slowness and stalling, as much as human decisions on the ground. Building a city in a flood plain, for example, is just asking for it. “My hunch is that signal would be greater than the anthropogenic signal of the storm itself,” he said. The 2015 study, however, didn’t analyze any changes in population or urbanization that, in the real world, strongly influence hurricane damages.

Lackman continues to test models that are useful in taking apart big storms, and he said he expects to give close attention to Harvey—the event itself and its many computer clones. But that’ll take a year or two, and this hurricane season isn’t even over yet. In fact, the letter “I” on the National Hurricane Center’s 2017 naming list was recently assigned: Tropical Storm Irma is on its way west.

© 2017 Bloomberg L.P

Join The Club

Join The Club