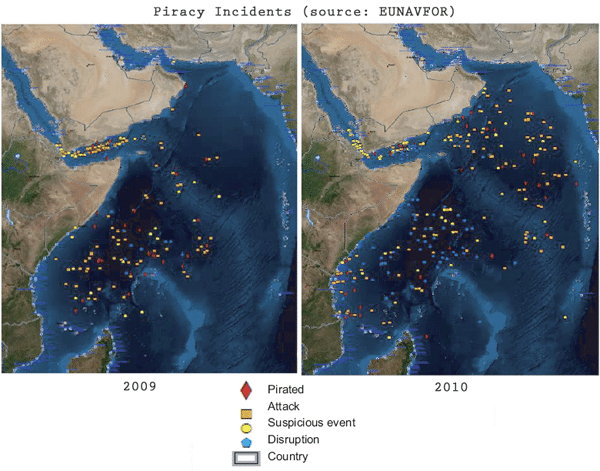

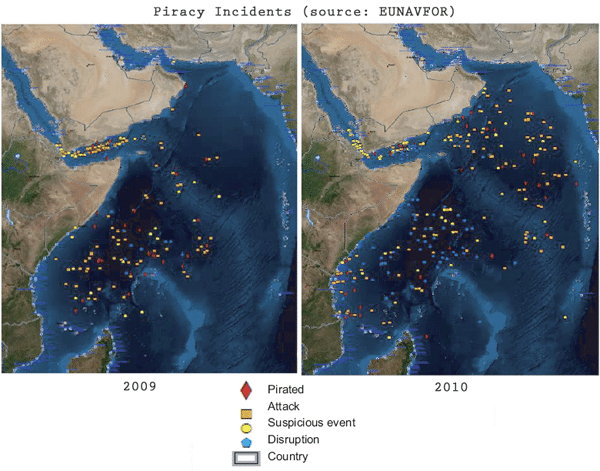

Over the last four years, piracy off the coast of Somalia has become an international phenomenon, plaguing shipping in the Indian Ocean and resisting attempts by the international community to contain it. Despite a high level international response that has included nine UN Security Council resolutions and three different multi-national naval operations, the numbers of vessels affected each year keeps growing: in 2007, there were 55 attempted and successful attacks by Somali pirates. By 2010, that had almost quadrupled to 219. Over the same period, over 3,500 seafarers have been held hostage, and 62 have been killed.

In January 2011, Jack Lang, a former French Foreign Minister who now advises the UN on piracy, warned that Somali pirates were becoming the “masters” of the Indian Ocean. The first three months of 2011 saw piracy attacks worldwide hit an all time high, largely driven by piracy off the coast of Somalia. From January to March 2011, the International Chamber of Shipping recorded 97 by Somali pirates, averaging more than one a day. Fifteen ships were successfully hijacked and 299 crewmen taken hostage. The rise in attacks coincided with an increase in violence, with seven seafarers killed and 34 injured worldwide. We note that some observers have attributed the recent rise in piracy off the west coast of Africa in the Gulf of Guinea to copycat attacks, and that this is also a concern. However, while lessons should be learned from the experience with Somali piracy, such as the importance of swift intervention, piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has on the whole followed a different model to that of Somali piracy.

Bringing Pirates to Justice

Around nine out of 10 piracy suspects detained by forces engaged in multinational operations are released without trial. The fact that most pirates are simply returned to their boats or to Somali land has engendered strong criticism from the shipping industry. According to the Chamber of Shipping, “the repeated images of pirates being released without trial by naval forces, including by the Royal Navy, causes understandable derision”. However, Henry Bellingham warned that these release statistics can be misleading, and that most of those released were not actually captured during an attack:

It is also worth bearing in mind that most of the so-called catch and releases have been the result of disruption activities with naval vessels going in quite a lot closer to the shore and intercepting skiffs. Of the cases of actual attacks on vessels and attempted acts of piracy that resulted in capture by the Navy, very few have resulted in catch and release, because if an attack has been made on a vessel, you have the evidence.

The Foreign Secretary also argued that disrupting pirates without detaining them still has merit:

Though unsatisfactory as an outcome, the pirates are at least temporarily disrupted as any equipment which could be used in a piracy attack, such as expensive engines, ladders or weapons, is seized and, most likely, destroyed.

The perceived failure to prosecute piracy suspects has been the subject of considerable criticism from some in the industry, who believe that prosecutions would constitute an important deterrent to the pirates. This criticism was voiced by the Baltic Exchange, which accused the UK of holding a particularly poor record:

The UK has gained a degree of notoriety within the international shipping community for its failure to prosecute those caught red-handed in the act of piracy. Once captured, pirates caught by UK forces are widely perceived simply to receive sustenance and medical assistance before being returned to the mainland unmolested. Seventeen countries (including France, Germany, Spain and the United States) placed more than 850 pirates on trial in the 12 months prior to April 2011″.

The Government has recently confirmed that in the past two years 21 pirates have been transferred to other states by the Royal Navy for prosecution, and between April 2010 and 11 November 2011, 60 further suspected pirates were released after being encountered during boarding operations because “it was assessed that a successful prosecution was unlikely”. Since making this statement, a further seven suspected pirates have been detained by Royal Navy forces and transferred to the Seychelles for prosecution.

In response to this criticism, the Minister argued that prosecutions are indeed taking place, stating that “I can understand the frustration of catch and release occurring, but it is worth saying that more than 1,000 pirates are now in custody around the world, so there is no impunity”.

Practical Difficulties

Captain Reindorp described the considerable practical challenges of detaining and transferring suspects who are captured in the Indian Ocean:

You could be doing this 1,800 miles out into the Indian Ocean; it would take you five or six days to get a pirate back if you had to steam him back, and you may not want to send your one and only helicopter off to do that, because that might be better used looking out for and trying to deter and interdict pirate operations. This is not simply an issue of jurisdiction; it is also an issue of practice, which comes from the unique maritime environment in which it is happening.

He expanded on the choice between allocating resources to pursuing prosecutions, rather than conducting deterrent operations:

whilst all this is going on, a ship is not performing its primary role which is deterring pirates, so you have to decide whether you are going to chase an ever-decreasing possibility of a successful prosecution or go back and deter pirates.

Evidence

We heard repeatedly that a major obstacle to achieving more prosecutions was the difficulty in gathering sufficient evidence of the act of piracy.

Dr McCafferty stated that:

with a burglar in your house, you have evidence of burglary. The challenge in the Indian Ocean, as we’ve said, is catching the pirates in the act with the evidence. Where we have been able to put evidence together, the UK has been successful in prosecuting pirates, albeit a small number. The challenge is always finding enough evidence that will convince the local authorities or countries in the region to try to prosecute.

As Dr McCafferty noted, the pirates are able to dispose of evidence quickly and permanently: “when they see a naval vessel approaching, they will often throw the paraphernalia overboard, and then we do not have the evidence which with to chase a prosecution”.

In addition to concrete evidence, witness testimony from those hijacked or under attack is important. The Minister told us that “The captain of a vessel has to be prepared to give evidence and you have to have crew members”. However, this evidence is not always easy to secure: Captain Reindorp stated that even in cases in which the UK had captured pirates and liberated hostages, the released hostages were unwilling to testify or to travel to courts in the region. He also noted that:

“There have been occasions when we take a boat and the first thing that the pirates do is pretend that they are hostages. Actually, it is really quite difficult to differentiate between the two”.

It is even more difficult to obtain evidence that suspects intend to commit acts of piracy. Distinguishing between pirates and ordinary Somali fishermen is not as easy as is sometimes supposed. Captain Reindorp described the problem:

We have to be able to differentiate four Somali gentlemen in a small boat with AK47s, which they will usually say that they carry for self-protection from pirates, from pirates, who may well also look like four Somali gentlemen in the same boat, with exactly the same weapons.

Even if suitable evidence is found, a number of states in the region do not have laws against going equipped or with intent to commit piracy, but only against an act of piracy itself. The Minister told us that four states in the region had a law against going equipped or going with intent, and that “what we want is for countries like Kenya, Tanzania and Mauritius to change their laws as well”.

We conclude that gathering evidence to secure a successful prosecution for piracy is challenging. However, not all claims made by the Government about the difficulty in securing evidence were wholly convincing: when pirates are observed in boats with guns, ladders and even hostages, it beggars belief that they cannot be prosecuted, assuming that states have the necessary laws in place and the will to do so. We urge the Government to pursue alternative means of securing suitable evidence (such as photos or video recordings of pirates with equipment, and supplying witness testimony by videolink). We urge the Government to engage with regional states to agree consistent and attainable rules on evidence required for a piracy prosecution.

For the entire report, including references, please click here.

Editorial Standards · Corrections · About gCaptain

Join The Club

Join The Club