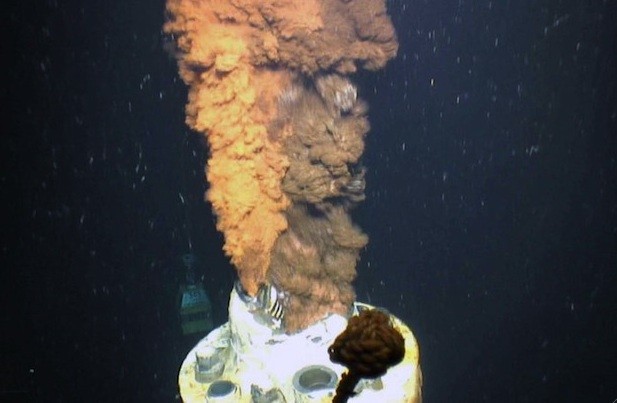

Oil spews from the Macondo well in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico following the April 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey via WHOI)

By Margaret Cronin Fisk and Allen Johnson

Sept. 30 (Bloomberg) — BP Plc, seeking to reduce potential water-pollution fines of as much as $18 billion, is trying to convince a judge that less oil spilled in the 2010 Gulf of Mexico disaster than the U.S. claims and that it capped the deep-sea gusher as quickly as possible.

U.S. District Judge Carl Barbier in New Orleans, who is presiding over the trial that began today, is already weighing whether the company’s actions in causing the April 20, 2010, blowout and subsequent spill reached the level of gross negligence, which would trigger higher fines and punitive damages.

Decisions in phase two of the trial, covering the size of the spill and BP’s efforts to contain it, might mean billions of dollars to the company and its co-defendants.

“The evidence will show BP’s outright lies caused the oil to flow” for 87 days, plaintiffs’ attorney Brian Barr said today in his opening statement.

A finding by Barbier supporting BP’s assessment, that the spill was 40 percent smaller than the government’s estimate, could shave as much as $7.5 billion from the maximum fines the company faces under the U.S. Clean Water Act. A finding that BP’s actions let the spill continue for longer than it might have could save its co-defendants, Transocean Ltd. and Halliburton Co., as much as 70 percent of any judgments against them.

‘High-Risk Gamble’

“It’s a high-risk gamble for both sides,” said John Levy, an attorney in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, specializing in complex litigation, including maritime and environmental law.

“The judge is probably going to compromise” on the volume estimates, said Levy of Montgomery McCracken Walker & Rhoads LLP. Given the participation by the U.S. government and other experts in the spill response, getting a judge to find gross negligence will be “a long shot for the plaintiffs,” he said.

BP has taken a charge of $42 billion related to the spill, according to its earnings statement released in July. The company has spent more than $26 billion including cleanup and claims, BP said on its website.

BP shares fell as much as 40 percent in the weeks after the blowout and remain down 31 percent from the day before the incident.

The trial “is still weighing on the shares,” said Peter Hutton, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets in London. “Investors are rightly concerned about the risks.”

Spill Victims

Lawyers for the plaintiffs and the primary contractors on the project, Vernier, Switzerland-based Transocean and Houston- based Halliburton, claim BP delayed capping the well by misrepresenting the size of the spill and the chances of the first effort to contain it. The spill victims also claim that BP wasn’t prepared for a deep-water blowout.

“BP willfully, with the intent to deceive, misrepresented its knowledge of the flow rate causing it to eschew available source control methods that would have stopped the flow of oil weeks earlier,” lawyers for the plaintiffs and co-defendants said in a Sept. 18 court filing.

BP has countered that its estimates on the flow rate weren’t used to determine which method to use to stop the gusher and that it tried the safest option first. The London-based company also contends the U.S. approved and oversaw all the decisions on capping the Macondo well.

‘Overarching Principle’

“One overarching principle governed the team’s work, ‘Don’t make it worse,’” BP lawyers said in court papers. The joint BP and U.S. well-control team’s goal of minimizing the risk of causing an uncontrollable underground blowout “accounted for the time required to shut in the Macondo well,” the company said.

“No one wanted to close the Macondo well more quickly than BP, but BP was faithful to the key principles that guided the entire source control effort, which was to proceed with caution and to obey the direction of the federal leadership,” company lawyers said in court papers.

The blowout of the Macondo well off the coast of Louisiana in April 2010 killed 11 people aboard the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and set off the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. The accident sparked hundreds of lawsuits against BP, as well as Transocean, owner of the rig that burned and sank, and Halliburton, which provided cement services for the project.

First Phase

The first phase of the trial, which started in February, addressed actions by BP, Transocean and Halliburton leading up to the explosion in the Macondo well and the sinking of the Deepwater Horizon.

The second phase, which began today, is split into two parts, with this week considering allegations that BP’s failings caused the spill to last longer. The second part, beginning next week, will determine how much oil was spilled into the Gulf of Mexico.

The U.S. government contends BP’s well spewed 4.2 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico before it was capped almost three months later. BP estimates the flow at 2.45 million barrels. Both agree that their numbers would have been higher if 810,000 barrels hadn’t been captured by a siphoning device at the wellhead before it could spill into the Gulf.

Barr today called the government regulators’ approval of the spill response plan “irrelevant.”

“The government is not in the business of drilling wells. That’s BP’s business,” he said. “BP’s plan was nothing more than a plan to plan.” BP knew as early as 1991 that “it needed to do more” to prepare an oil spill response, he said.

$18 Billion Possible

If the company is found by Barbier to have acted with gross negligence in causing the explosion or extending the spill, it faces a maximum penalty of $18 billion under the Clean Water Act, using the government estimate, and a maximum of $10.5 billion, using the BP assessment. The maximum fines if Barbier rejects gross negligence would be $2.7 billion under the BP assessment and $4.6 billion using the government numbers.

Under the U.S. Clean Water Act, polluters face a penalty ranging from $1,100 to $4,300 for each barrel spilled, depending on a variety of factors, including whether the polluter acted in a grossly negligent or reckless manner in causing the spill.

The nature and extent of injuries to natural resources “may also turn in part on the quantity of oil released,” Justice Department lawyers said in a Sept. 5 filing. BP still faces unspecified billions of dollars in additional expenses to restore the damaged gulf coast environment, under U.S. law.

‘Fully Accountable’

“We will continue to present our case on behalf of the United States to ensure that those responsible for the April 2010 Deepwater Horizon disastrous oil spill are held fully accountable,” Wyn Hornbuckle, a Justice Department spokesman, said in a statement before trial.

Transocean and Halliburton, defendants in the first phase of the trial over the fault for the blowout, are aligned in this phase with the plaintiffs suing BP, including the states of Louisiana and Alabama. The two contractors contend that the well could have been capped as early as May 15, 2010, reducing by about 70 percent the amount of oil ultimately spilled.

“Transocean and Halliburton will prove that BP’s misrepresentations and omissions delayed the capping of the well, and that this fraud therefore is a superseding cause of any oil that spilled into the Gulf after the well would have been capped,” their lawyers said in a Sept. 18 filing.

Blowout Preventer

The co-defendants and plaintiffs claim BP was grossly negligent in its response to the spill. BP denies any negligence, much less the higher allegation of gross negligence.

The allegations revolve around a method BP used to try to cap the well, called Top Kill, which involved pumping drilling mud and other material into the Deepwater Horizon’s blowout preventer, which was still atop the well on the sea floor. Top Kill failed in late May 2010 and the well wasn’t capped until July.

BP rejected another proposed method, called BOP-on-BOP, which would have landed a second blowout preventer onto the lower portion of the failed Deepwater Horizon blowout preventer, because it would have precluded using an alternate solution if that effort failed, the company said.

The plaintiffs and co-defendants contend BP knew Top Kill wouldn’t work. “BP learned in May, but concealed from government decision makers, that based on BP’s own internal flow rate estimates, the Top Kill was unlikely to succeed,” their lawyers said in court papers.

Top Kill

After the attempt failed, “BP falsely claimed that the only plausible explanation for the Top Kill’s failure was the supposed rupture of pressure relief disks in the well,” they said. “No such rupture ever occurred. Based on that false assessment, BP recommended that the BOP-on-BOP option be abandoned.”

The well was finally capped on July 15, 2010, through the use of a device called a capping stack. The plaintiffs claim BP should have had this device available before the blowout.

The capping stack was a unique response to a unique event, BP has countered in court papers. The government has never required having a pre-built capping stack and no one in the oil industry has ever had one, BP said.

The source control part of this phase of the trial is scheduled to last one week. The segment on quantification of the spill is scheduled to take three weeks.

Barbier hasn’t indicated when he will decide on this phase, or on the issues of fault and gross negligence, which were tried in the first one.

Anadarko Petroleum Corp. is also a defendant in the segment determining the size of the spill. The U.S. has claimed that Anadarko, as an owner of a 25 percent share of the well, is liable for Clean Water Act fines, though Barbier ruled it can’t be held responsible for the incident or the response.

The case is In re Oil Spill by the Oil Rig Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010, 10-md-02179, U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Louisiana (New Orleans).

Copyright 2013 Bloomberg.

Join The Club

Join The Club