How Are Structures Built Underwater?

Despite being beautiful and useful, rivers, lakes, harbors, and oceans are not always the best places to build. Tools and construction materials work better when they are above water and...

Updated: February 28, 2019 (Originally published November 25, 2018)

By Michael Carr – “SWITCH ON!” the diver yelled into the speaker inside his Superlight 17 fiberglass diving helmet.

This command was received on the surface by the topside supervisor, who replied to the diver with the same words.

“SWITCH ON.” He then turned to the generator operator and repeated, “SWITCH ON.”

With this command, the generator operator, while wearing large rubber gloves, moved a large knife-switch to the closed position, and immediately 220 AMPS of electricity surged down large cables to a Broco cutting torch being held by the diver.

Immediately the generator’s RPMs reduced and you could tell by the sound it was under load.

What was happening below the surface was awe-inspiring. This surge of 220 AMPS of electricity arched across the gap between the generators grounding cable attached to the base of the cast iron lighthouse, and the tip of the Broco torch. (Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated 222 volts of electricity, not AMPS. Find out more on this in the U.S. Navy Underwater Cutting and Welding Manual or the AWS D3.6 Underwater Welding Code)

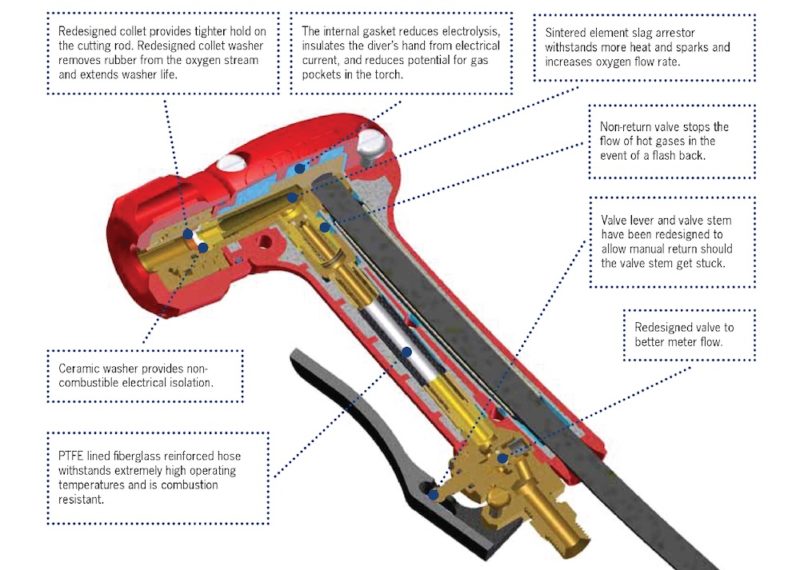

This massive arc of electricity ignited the magnesium rods inside the torch’s 18-inch long rod. Attached the torch’s handle was a rubber hose, which fed industrial oxygen from bottles on the boat.

When the diver squeezed the trigger on the Broco torches’ handle, high-pressure oxygen rushed through the magnesium rod, producing temperatures exceeding 10,000 degrees F.

Massive amounts of smoke, slag, and flames erupted as the diver pushed the Broco torch against the lighthouse’s base.

On the surface the diving supervisor knew what was happening, the unending clouds of smoke and debris erupted at the surface next to the Coast Guard 65-foot buoy tender supporting the diving operation.

“Hot shit,” the diver said to himself. “We are burning some metal today!”

He continued to push the burning rod into the lighthouse, rhythmically squeezing the oxygen trigger to increase the burning and blow out slag from the hole he was making into the lighthouse’s cast iron structure.

He continued to focus on this task until the burned rod was reduced to a length of just a few inches, and then he yelled into his helmet microphone:

“SWITCH OFF!”

“SWITCH OFF”, came back from the surface and the large Frankenstein-style knife switch was opened. Generator RPMs increased as the load was reduced.

“OK Red Diver?” came the call from topside to the diver.

“OK Red,” came back from the diver.

“Topside, this is Red Diver, one hole completed. Changing Rods.”

Onboard the Coast Guard 65-ft buoy tender a team of divers from the US Coast Guard Atlantic Strike Team were focusing on ensuring the air compressor, generator, oxygen tanks, and support gear were all working properly. Underwater cutting using a Broco torch, being fed by pure industrial oxygen is one of the most dangerous underwater evolutions. Only the use of explosives was more dangerous.

In particular it is crucial to keep the generators 220 Volt ground lead between the diver and the torch. Electricity takes the shortest route, and when it leaves the ground, looking for the Broco torch, it needs to find the torch tip before it finds the diver. With a torch burning at 10,000+ degrees, less than 2 feet from your face, your attention is uninterrupted and focused.

A single rod will burn for several minutes, and during this time the diver holds their position, while slowly and meticulously pushing the rod into and against what they are cutting, surrounded by smoke, flames, debris and noise.

Today this dive team was working on Wolf Trap Light, in Chesapeake Bay. Built in 1894 it was constructed with a cast iron and concrete base, several feet thick. The structure is sunk deep into the muddy Chesapeake Bay bottom, and its light powered by an underwater electrical cable coming from the shore.

When the cable reaches Wolf Trap light, it comes up the outside of the light structure, and enters through a porthole about 20 feet above the water. During winter months, when ice forms on the Chesapeake Bay, this cable often becomes damaged, and torn from the outside of the lighthouse by ice flows.

To protect the cable, Coast Guard engineers designed a heavy steel cover to go over the cable. This cover reaches down to the seabed and up to the cable’s porthole entrance. But how to attach the cover, ensuring massive ice flows do not wrench it off?

When consulted about this earlier in the year the Coast Guard Dive Team quickly responded:

“No problem, easy day,” the Dive Team leader said. “We will blow holes in the side of the lighthouse using our Broco torch, then insert threaded expandable fittings. We will seal the threaded fittings with underwater epoxy, and then we can bolt the cover directly to the lighthouse base. When do you want to start?”

At first the Coast Guard Engineers were surprised at the quick response. “Are you sure this will work, don’t you want more time to study possible options?” they asked.

“No,” said the Dive Team leader. “We got this, when do you want to start?”

And off they went, working the many Chesapeake Bay cast iron Lighthouses; Thimble Shoals, Point Lookout, Point No Point, Wolf Trap, Sharps Island, and others.

They started this operation, on Wolf Trap Light, early in the morning, and all day they burned holes in the side of the light, mixed epoxy, inserted threaded sleeves, and moved to the next hole.

“SWITCH ON.”

“SWITCH OFF.”

Slow and steady, as the boxes of magnesium broco torch rods slowly emptied.

By late afternoon all the holes, below and above the waterline, were ready. A block and tackle and the boat’s buoy crane were used to hoist the massive steel conduit so it could be bolted into place.

Pneumatic hammers drove the bolts into the sleeves, both above and below the waterline, and the cable was securely protected.

“OK”, said the Diver Supervisor. ”Well done, but there is one last task on our checklist.”

All the divers knew what he was referring to, and they began suiting up in their SCUBA gear. Set aside was the massive surface supplied diving gear, which had been used all day for the cutting operation. The generator was shut down, oxygen bottles secured. All was quiet on the boat now.

“We have one hour to get this done,” said the dive supervisor, so get as many as you can, but focus on the big ones!

They were going to collect oysters! Oysters grow around the base of these lighthouses, but are never harvested because oyster boats cannot get in near the lighthouse base. All day, as the divers blasted holes in the lighthouse base, they could see hundreds of huge oysters.

An hour of diving now produced bushels of large juicy oysters.

“Damn these look good,” all the divers said, “let’s get back to the station!” An hour transit brought them to the small Coast Guard Boat station behind Gywnns Island. As they pulled up to the dock the Stations Officer-in-Charge came out to meet them.

“How did it go?” he asked.

“Great!” replied the Dive Team leader, “The steel cover is on, your crew was great, and we have a tons of oysters!”

“Just what I expected!” said the BM1. “We have cold beer over by the boathouse!” And so the divers, boat crew, and station personnel all gathered under the shade of the boathouse, drank cold beer, sucked down fresh oysters, and told sea stories.

It was the best way to end a hard working day, sharing food and drink with fellow sailors.

Sign up for gCaptain’s newsletter and never miss an update

Subscribe to gCaptain Daily and stay informed with the latest global maritime and offshore news

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up