Catastrophe In The Heart Of The Sea

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by gCaptain in 2016 and is being republished now because it’s lessons are timeless and possibly more relevant in 2022 as today’s ships...

Updated: April 17, 2023 (Originally published December 16, 2011)

What fundamentally hasn’t changed in the 100 years since the Titanic?

What fundamentally hasn’t changed in the 100 years since the Titanic?

One hundred years ago today Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast Ireland was putting the final touches on a ship that would hold the title of the world’s largest passenger liner but her glory would be brief. On 15 April of the following year, 1912, she would claim a more ominous title as the world’s most infamous ship. Her name was the RMS Titanic.

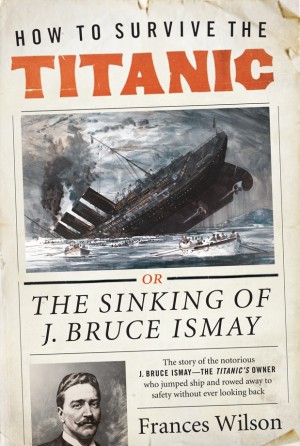

Scores of books have been written chronicling the disaster but few take the time to understand the men behind the tragedy. In a new book titled HOW TO SURVIVE THE TITANIC, Award-winning historian Frances Wilson

delivers a gripping account of the incident. By investigating the ship’s collision and sinking through the prism of the demolished life and lost honor of the ship’s owner, J. Bruce Ismay, Wilson brings a bright new perspective to the event raising provocative moral questions about cowardice and heroism, memory and identity, survival and guilt—questions that revolve around Ismay’s loss of honor and identity as his monolithic venture —a ship “The Unsinkable” — was swallowed by the sea and subsumed in infamy forever.

The book is more than a gripping tale of survival, it’s also a window into the role ship managers and shipping tycoons play in the instigation of maritime tragedies. The consolidation of major shipping and energy companies in recent years have created mega-conglomerates like Transocean and BP, companies in which CEO’s are responsible for the management of increasing risks and operational complexity.

While modern technology and regulations have made sweeping changes to the operation and safety of ships since the Titanic, as told by Wilson, the fundamental cause of disaster is the human element. The character, motivations and personality of CEO’s play an important role in safety at sea. This, unfortunately, has not changed.

The fundamental element of human nature and corporate decision-making on ship safety is just as relevant today as it was 100 years ago.

To help us understand the role of Ismay, the ship’s master Captain Smith and other executives responsible for the Titanic’s sinking, gCaptain sat down with Frances Wilson for the following exclusive interview:

John Konrad: What were the personality or cultural differences that caused Capt Smith to stay and Ismay to leave?

Frances Wilson: The crucial difference, as far as Ismay was concerned, was one of role. Smith was the Captain and therefore expected to go down with the ship, while Ismay, as chairman of the White Star Line, was in an ambiguous position when it came to survival. He was neither a member of the crew (with a duty to die) nor a regular passenger (he had not paid for his ticket). The subsequent inquiries into the disaster suggested that Ismay was a ‘Super Captain’ and should therefore have sacrificed his life, but he argued that he had no authority over Captain Smith, that he was simply on board the Titanic to report back faults in her design and possible improvements. Ismay left the ship, I believe, because he fell through all the important categories, but also because he had no identification with those men on board who were lighting up their last cigarettes and preparing to die. Ismay saw himself as a man who belonged to no particular group, and therefore as someone who could act according to personal will rather than social expectation.

John Konrad: If there had been enough lifeboats for every man, woman and child would Capt. Smith still gone down with the ship?

Frances Wilson: I think so. Smith seems to have collapsed more or less the moment he realized the Titanic was doomed. He had no desire to go on and live with the responsibility of the tragedy.

John Konrad: In your research what new information most disturbed you?

Frances Wilson: Without doubt, Ismay’s letters to Marian Thayer in the immediate aftermath of the wreck. They shine a bright light into a dark corner: this is the voice of a man trying to bare the unbareable. Most striking is the urgency of his desire to talk – Ismay, a man who has never wanted to talk to anyone, writes again and again that wishes he could talk to her in person, and that only she could understand what he is going through. Otherwise the letters repeat that the wreck had nothing to do with him, that he can’t function any more and that he feels bitter about his treatment at the hands of the press and the Inquiries. What transpires is Ismay’s sense that no one is suffering as much as he is: that other survivors are treated with generosity and pity, while he – who lost his ship as well as his reputation and has been blamed for the whole thing – receives no sympathy at all.

John Konrad: Besides Smith and Ismay who is most accountable for the disaster?

Frances Wilson: The Titanic’s designer. Thomas Andrews. Because Andrews went down with the ship he was seen as a hero rather than as accountable.

John Konrad: Today mariners complain that technology allows ship owners to micro-manage operations from afar. Did Ismay’s presence contribute to the outcome? If so… would the titanic still have sunk if he wasn’t aboard at the time?

Frances Wilson: The conclusion drawn by the US Inquiry was that Ismay’s presence on the ship had an ‘unconscious’ effect on Captain Smith. It’s an interesting term to use, given the birth of psychoanalysis at the time. What the inquiry was suggesting is that while it could not be proven that Ismay had ordered the Captain to keep up the ship’s speed prior to the accident, or to continue ‘Slow Ahead’ after the damage had been done, with his employer on board the Captain would have instinctively acted in accord with Ismay’s wishes. But my guess is that Titanic would have sunk even without Ismay on board, because of Smith’s insistence that ‘nothing but God could sink these ships’. Smith was becoming careless; six months earlier he had been responsible for a serious accident while he was commander of the Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic. The fact that the Olympic stayed afloat with a fifteen-foot hole in her hull confirmed to Smith that these ships were unsinkable.

John Konrad: What was Ismay’s greatest fault?

Frances Wilson: Ismay’s greatest failing was his inability to communicate. He hid his acute shyness behind a cold, charmless, domineering exterior which made him appear machine-like. Had he been able to use words to any effect in the US and British Inquiries he would not have come across as a more sympathetic figure to the press and the public. Instead he seemed inhuman in his clinical responses, indifferent to the catastrophe he had been a part of. What interested me was how he communicated with himself, how he lived with what Joseph Conrad called ‘the acute consciousness of lost honour’ without the use of language to help him through.

John Konrad: What lessons from the titanic (or Ismay) are still pertinent to executives today?

Frances Wilson: Do not put your faith in bigness.

Sign up for gCaptain’s newsletter and never miss an update

Subscribe to gCaptain Daily and stay informed with the latest global maritime and offshore news

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up