By Paul Burkhardt

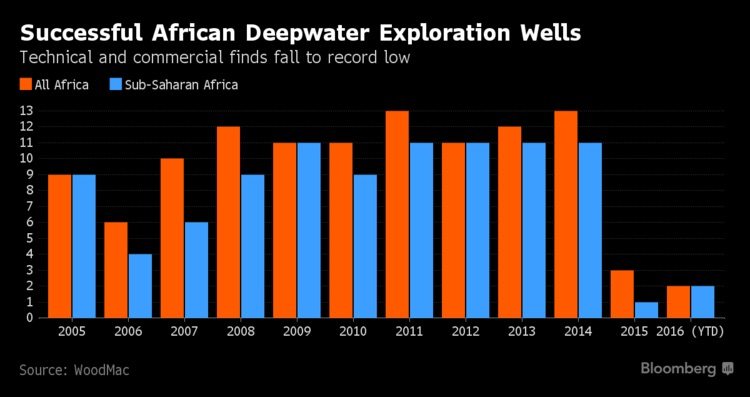

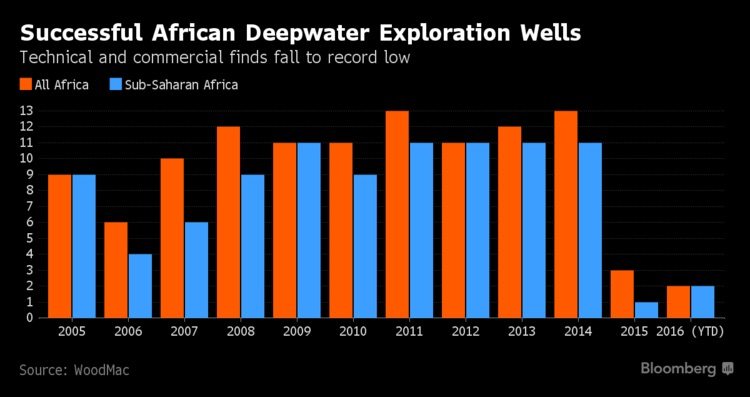

(Bloomberg) — Drillers burned by a two-year slump in crude prices are slowing exploration of deep-water prospects off the coast of Africa, undermining a key driver of growth on the continent.

In the 25 years since 1982, African oil output doubled to more than 10 million barrels a day. Now, with prices sitting below $50 a barrel, international drillers have cut their plans for capital expenditure in the next five years by $100 billion, according to a Nov. 2 report by Wood Mackenzie Ltd. The change could drop the region’s oil production 46 percent by 2030, the report said.

Hardest hit: Nigeria and Angola, countries that are already struggling economically and depend on oil for almost all their foreign income. To revive deep-water exploration on the continent, crude prices would have to rise to $60 to $70 a barrel, according to Keith Myers, managing director of the consulting firm Richmond Energy Partners.

“Africa suffered the most of any region in terms of the decline in frontier exploration,” Myers said in an e-mail. Deep-water exploration was “the driver for production growth in the region.”

In September, the number of offshore oil and gas rigs in Africa fell to just nine, down from a high of 48 in November 2014, according to Baker Hughes Inc. data. That’s the lowest level in more than a decade. Overall, the number of rigs on the continent dropped to a five-year low of 77.

“We’re being more disciplined,” said Oliver Quinn, director of Africa and global new ventures at Ophir Energy Plc, speaking at the Africa Oil Week conference in Cape Town this month. The London-based explorer has plans to drill three to five frontier wells over the next two years, split between Africa and Asia, according to Quinn.

“We don’t want to go out and spend capital that we can’t replenish to do exploration,” he said.

Nigeria, the continent’s biggest oil producer and most populous nation, is dependent on the fuel for more than 90 percent of its foreign income. The country, facing ongoing violence in its crude-producing Niger Delta region, saw inflation accelerate to an 11-year high in October as revenues from oil tumbled and import costs for consumer goods and machinery rose.

Angola, which depends on oil for almost all its exports, said in July it was generating “barely enough” revenue to pay off its debt.

Exxon Mobil Corp., Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Total SA are among the biggest players in Nigeria, where deep-water fields have so far escaped the militant attacks that curbed output in the Niger Delta. The biggest deep-water producers in Angola include BP Plc, Exxon and Chevron Corp., which canceled an ultra-deep water semi-submersible rig with Maersk Drilling Services A/s at the end of March.

Shallower Water

Tullow Oil Plc has turned away from deep water, even as the Africa-focused explorer prepares to renew its hunt for new discoveries on the continent. The company is more focused on “shallower water” prospects, said Tullow Chief Executive Officer Aidan Heavey.

In relation to exploration, “a dollar spent today is probably the same as $3 spent a couple of years ago,” Heavey said in an interview in Cape Town.

Over the past decade, sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 42 percent of global deep water frontier drilling, according to Richmond Energy Partners. That kind of exploration is key to sustaining output in the longer term, Myers said. With the lower price of crude, however, global companies are increasingly looking for easier access to their product.

Brent, the global benchmark, is down 41 percent in the past two years. The contract for January settlement was little changed at $46.55 a barrel on the London-based ICE Futures Europe exchange at 11:02 a.m. on Friday.

As an example, Houston-based Noble Energy Inc., which has assets off the coast of Equatorial Guinea, this year will focus two-thirds of its $1.5 billion in spending on U.S. shale. Companies have to “justify investment in new deep water projects,” said Susan Cunningham, executive vice president of exploration and new ventures at Noble, in an interview in Cape Town this month.

“We’re not going to be doing much in deep water” for the next two years, she said.

Battered by falling oil prices, some African governments have been slow to trim the share of profits they take from deep-water projects, deterring investment.

“Deep water can still work but you need to make sure that the fiscal terms in the country you are operating will generate a return in the current commodity price environment,” said Geoff Callow, investor relations manager at Ophir Energy. “Some governments are adjusting terms and they are seeing investment and others are being slower to adjust and are consequently finding it harder to attract investment.”

© 2016 Bloomberg L.P

Tags:

Updated: February 5, 2026 (Originally published November 18, 2016)

Editorial Standards · Corrections · About gCaptain

This article contains reporting from Bloomberg, published under license.

Join The Club

Join The Club