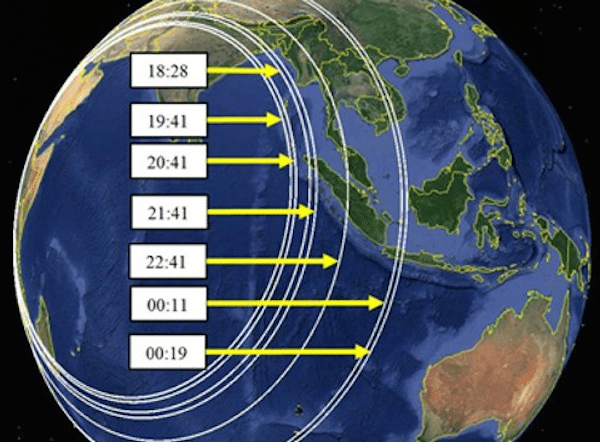

There were 7 “handshakes” between the ground station and the aircraft after the loss of primary radar data. The location rings, shown here, are calculated from the recorded “burst timing offset”. Source: Inmarsat/Boeing /Google

By Stuart Grudgings

KUALA LUMPUR, May 27 (Reuters) – Malaysia’s government and British satellite firm Inmarsat on Tuesday released data used to determine the path of missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370, responding to a clamour from passengers’ relatives for greater transparency.

The data from satellite communications with the plane, which runs to 47 pages in a report prepared by Inmarsat, features hourly “handshakes” – or network log-on confirmations – after the aircraft disappeared from civilian radar screens on March 8.

Families of passengers are hoping that opening up the data to analysis by a wider range of experts can help verify the plane’s last location, nearly three months after the Boeing 777 with 239 passengers and crew disappeared.

In-Depth: Considerations on defining the MH370 search area

The data’s release had become a rallying cry for many of the families, who have accused the Malaysian government of holding back information.

“When we first asked for the data it was more than two months ago. I never dreamed it would be such an obstacle to overcome,” Sarah Bajc, the American partner of a passenger, told Reuters from Beijing.

Based on Inmarsat’s and other investigators’ analysis of the data, the aircraft is believed to have gone down in the Indian Ocean off western Australia.

Malaysian investigators suspect someone shut off MH370’s data links making the plane impossible to track, but investigators have so far turned up nothing suspicious about the crew or passengers.

In the hours after the aircraft disappeared, an Inmarsat satellite picked up a handful of handshake “pings”, indicating the plane continued flying for hours after leaving radar and helping narrow the search to an area of the Indian Ocean.

The dense technical data released on Tuesday details satellite communications from before MH370’s take-off on a Saturday morning at 12:41 a.m. local time (1641 GMT) to a final, “partial handshake” transmitted by the plane at 8:19 a.m. (0019 GMT). The data includes a final transmission from the plane 8 seconds later, after which there was no further response.

The data also featured two “telephony calls” which an Inmarsat spokesman said were made by Malaysia Airlines from the ground, at 1839 GMT and 2313 GMT and which went unanswered by the plane. The spokesman said the existence of the two attempted calls was already in the public domain before Tuesday’s data release.

Malaysian officials were not immediately available to answer questions on the data.

A spokesman for Inmarsat said the company had released all the data it had associated with the flight.

“These 47 pages represent all the data communication logs we have in relation for MH370 and that last flight,” he said.

Bajc said experts on flight tracking who have been advising the families would now be able to analyse the data to see if the search area could be refined and determine if Inmarsat and other officials had missed anything.

But she complained that the report released on Tuesday was missing data removed to improve readability, as well as comparable records from previous flights on MH370’s route that the families had requested.

“Why couldn’t they have submitted that?” she said. “It only makes sense if they are hiding something.”

Calculations based on the pings and the plane’s speed showed the jetliner likely went down in the remote ocean 7 to 8 hours after its normal communications were apparently cut off as it headed to Beijing on its routine flight. The time of the last satellite contact was consistent with the plane’s fuel capacity.

The search in an area around 1,550 km (960 miles) northwest of Perth, Australia was further narrowed on the basis of acoustic signals believed to have come from the aircraft’s “black box” data recorders before their batteries ran out.

After the most extensive search in aviation history failed to turn up any trace of the plane, however, officials have said that it could take a year to search the 60,000 sq km (23,000 sq mile) area where it could have come down.

Malaysia, China and Australia said in mid-May they had agreed to re-examine all data related to the missing plane to better determine the search area as the hunt enters a new, deep-sea phase.

Malaysia is also leading an official international investigation under United Nations rules into the causes of the baffling incident. (Reporting by Stuart Grudgings; additional reporting by Sarah Young; Editing by Christopher Cushing)

© 2014 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved.

Join The Club

Join The Club