Maritime businesses are tempting targets for criminals; here’s what companies and mariners can do to harden operational security.

By David S. Lewis

In the military, operation security (“OPSEC” for a crisp, military-style abbreviation) isn’t just a buzzword: it’s a way of life. It refers to using a systematized process to assess, evaluate, and counter adversarial threats, including physical security, information security, cybersecurity, and other threat vectors.

In the private sector, however, far fewer workers and companies take day-to-day OPSEC as seriously as is warranted. Routines and patterns lull us into an atmosphere of complacency, and we spend little time assessing whether we are vulnerable to attack from malactors. As a result, attackers have the element of surprise on their side, and conversely, those put on the defense are without a plan for it.

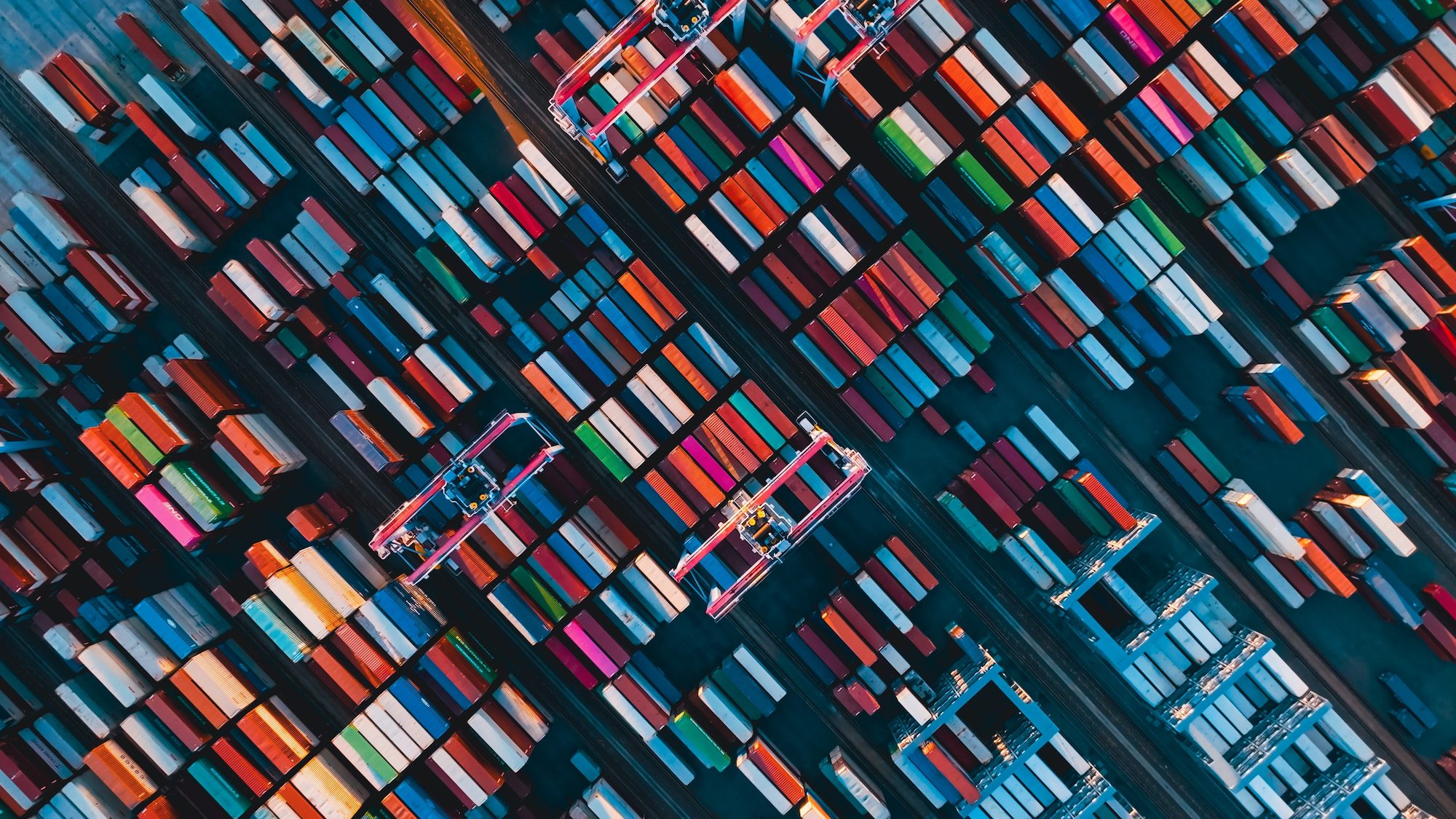

By the nature of our work, mariners are often de facto guardians of critical infrastructure, and are responsible for conveying billions of dollars’ worth of goods. We are often working in places that are new or unfamiliar, and port cities have historically been higher-value targets for both common criminals and political belligerents like terrorists. We might not like to admit it but our vessels, companies, and systems are vulnerable: when there’s only 20mm of steel between you and eternity, it pays to pay attention. When was the last time your company briefed you on the security aspects of your day-to-day job? And what can you do to protect yourself and your loved ones?

Fundamentals of security

At its core, OPSEC involves anticipation, preparation, and practice. To maintain effective operational security, we have to know what we’re securing. Critical information, such as sailing schedules, port security procedures, manifests and station bills, and standard operating procedures are just some of the data that can be used to effectively target an attack. And in today’s technology-driven world, many of us carry a warehouse’s worth of critical information around in our pockets.

Once we’ve identified the assets that could be targeted, we must then assess the threat level against them. That threat assessment should reflect the actual environment in which the operation is being conducted, and identify the likely sources of those threats. Become the would-be attacker, and probe your systems and practices. Where would you target? When? Consider the risk-reward ratio: what’s the easiest vulnerability to exploit for maximum impact?

Assume the malactor knows everything you know, and find ways to harden those weaker, more inviting parts of the system. In port, could someone with access (such as a worker) board your ship without permission? Do your watchstanders actually challenge those coming aboard, or just pass a glance over ID cards, assuming visitors with a badge are who they claim to be?

The same philosophy applies to your ship’s IT systems. If you wished to gain access to the network and weren’t a crew member, what would it take to get to a station with a USB drive? Even a request that seems innocent, such as to print off a document from a a computer station, can involve a significant security risk.) To gain a sensitive password and a moment at a workstation? As you sound your electronic security systems, be creative, because the adversary is. Last week whistleblower France Haugen testified to the US Congress that the social media giant was aware of individual and state actors, including known sponsors of terrorism, utilizing their service to conduct espionage against public and private entities. And it bears mentioning that as of 2020, all four of the largest shipping carriers (CMA CGM, Maersk, Mediterranean, and COSCO) have all suffered devastating cyber attacks in the last five years, with total losses likely over $300 million. The most costly cyberattacks on shipping companies usually target shore-based networks and facilities, but attacks on shipboard systems do happen, often gaining more attention despite having localized effects. These attacks can result in failures across an array of discrete systems, even impeding navigation.

Few mariners, particularly those operating in congested areas, don’t occasionally imagine the effects of an attack on shipboard systems.

“If someone was crazy enough to take control of one and wedge it in the river so no traffic could go up or down, that’s going to be a huge financial lick for the whole country,” said the owner of a ship services company operating a fleet on the lower Mississippi. “I mean, commerce would stop in the vast majority of the country.”

That company owner, who asked to remain anonymous, citing concerns for his business, said that in spite of occasionally having concerns about OPSEC, he didn’t have a formal structure for training or briefing his own crews, and said he relied on a “see something, say something” philosophy.

“The people making deliveries to us are common vendors we’re familiar with, so we don’t worry about them much because we know them,” he said. “If we see something, we’ll call the police department. Or if someone’s hanging out on the barge fleet that we know shouldn’t be there.”

He said that his first point of contact would be the police, or maybe the Coast Guard.

“We’ve had instances where we’ve seen people going around and taking pictures of different facilities, and then you call the police; or if they’re flying drones where they’re not supposed to be, things like that.

“But nothing that has got me petrified or anything.”

Social Media and Smartphones

Due to the immense and relatively recent power afforded social media, it deserves its own treatment in a primer on OPSEC. Without proper security settings and general OPSEC considerations, your mobile devices are little more than a well-organized beacon of critical and sensitive information. From a security perspective, mobile devices have the potential to be the largest vulnerability in the average user’s life: a source of endless information for a savvy attacker, and also an excellent information-gathering tool for them. Many of us have stopped noticing people pointing phones at our vessels, without considering how much our systems can be documented with a few high-definition snaps. The utility of these tools for a malactor is astonishing and dirt cheap: from sophisticated cameras to facial-recognition software, GPS tracking to free AIS apps, eavesdropping to stealing passwords, smartphones can provide significant operational data to anyone who is curious about the outside of our vessels.

Social media can also provide many windows into their interiors. While most sea carriers have rules for employees posting online, they are often vague and rarely refer to the operational security component of the policy. As a result, those policies can be ignored or adhered to carelessly by some sailors who don’t understand the security ramifications, and policing employees’ social media profiles is a huge task for employers. It’s one thing to find an employee talking trash about a supervisor; but perusing the metadata from a legitimate photo posted by a crewmember can reveal troves of location data, patterns about vessel movement, cargos, port of call, and more. User bios often contain links to the social media of the companies that employ them, and so with a vested interest in gaining access, an attacker can learn enough about the individual employee to construct complex “phishing” attacks in an attempt to gain crucial network information of the vessel or company.

At a minimum, employees and mariners should receive training on the dangers of indiscreet posting. They should be extraordinarily careful not to post anything to indicate sailing schedules, manifest information and cargo composition, command details, and ports of call. Photos taken shipboard should be carefully scrutinized for compromising information, even in the backgrounds of the image; saboteurs and criminals would seek to gain every possible advantage from any image, even those that seem innocuous. Mariners should also turn off location-sharing features on their smartphones, and ensure that they are disabling metadata for photos and videos before posting them.

“It’s a whole different ballgame at this point, and I don’t know how you would control for it, except by limiting social media,” said marine logistics expert George Adams in an interview, adding that he had personally chosen to abstain from social media in part because of the additional risk exposure. His company, Management Marine Service, Inc., has multiple government contracts; captains and crew working for him have standing orders to never post anything about their work.

Adams may be more sensitive to OPSEC than many mariners because his background is in business aviation, where confidentiality concerns were treated the same as everything else in aviation: they became part of the “checklist.”

“I was the director of aviation, so it was my role to ensure that confidentiality requirements were met. We would have a briefing on that before every flight,” and noted that the briefings would include information from State Department publications as well as noting any cultural differences or unique security challenges present in the specific location to which they were traveling.

After the September 11 terrorist attacks, the business aviation industry took on increased security measures, including stricter pre-flight checklists. Adams’ role at his company included drafting protocols for operational security. He said that the key to OPSEC systems was organizational participation.

“Effective strategies require buy-in from all crew and other workers. One way to increase buy-in is to involve them in the process, by having them identify issues and challenges and to help write the materials, which I did,” said Adams. “…I was a unicorn in that respect,” he added.

David S. Lewis is a licensed master mariner (Mar. Ref. 8430779) and a veteran of the U.S. Navy, where he worked in a shipboard security capacity after the attacks of September 11, 2001. He currently is a subcontractor for the Department of Homeland Security and also runs a sailing charter in New Orleans.

Join The Club

Join The Club