Wojciech Wrzesien / Shutterstock

By Liam Denning (Bloomberg Opinion) — Energy dominance sure does seem to come with a hefty dose of self-flagellation.

The latest bit of America’s energy sector to feel the over-the-shoulder lash is the liquefied natural gas-export business. On Friday, LNG joined the list of goods that China will hit with tariffs in retaliation for U.S. ones. This is problematic when you consider China has taken 13 percent of U.S. LNG exports (and more like a quarter last winter), according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

As I wrote here about U.S. oil, a tariff imposed by one of the world’s largest importers of fuel will act as an effective tax on exporters. China buys U.S. LNG on the spot market, so its demand is very sensitive to the spread between benchmark U.S. natural gas prices and Asian prices. That spread has to absorb the cost of converting U.S. gas into a liquid (typically a 15 percent premium) and shipping it across the world (about $2 per million BTU via the Panama Canal, according to BNEF’s LNG Shipping Calculator).

Using futures prices for Henry Hub natural gas and the Japan-Korea Marker (JKM) as proxies, here’s what happens to the theoretical netback, or margin, of an exporter on the U.S. Gulf Coast selling LNG to Shanghai if a 25 percent tariff is imposed:

The really fun thing about the LNG trade, though, is that, like with most other trades, everything is connected. So apart from the LNG sector, these tariffs could really cause problems for a bigger business up the pipe: the Permian basin’s oil producers.

How so? A side-effect of the surge in Permian oil output is a similar surge in associated gas that comes up alongside it. As long as oil prices encourage more fracking for oil, the gas essentially comes for free. This is a problem in west Texas because, short of coming up with an ingenious method allowing local residents to breathe the stuff, there isn’t enough demand there to take it all. Hence, gas priced in Waha, Texas, trades at a discount of almost 80 cents per million BTU, or 28 percent, to the Henry Hub benchmark.

Read Also: Chinese Tariffs on LNG, Oil May Hit U.S. Bid for Energy Dominance

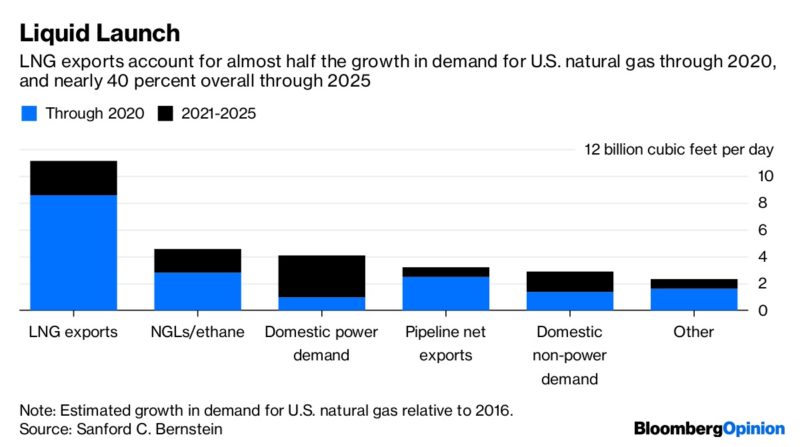

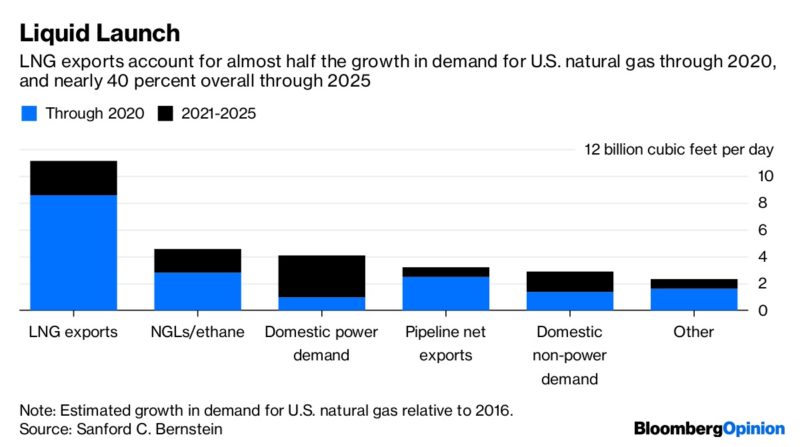

Just as lifting the crude-oil export ban helped alleviate a similar problem in oil a couple of years ago, so the ability to get gas to the Gulf Coast and ship it worldwide is a vital escape valve here. In an analysis published in May, Sanford C. Bernstein estimated that rising associated gas production – the vast majority of it from the Permian basin – would be enough to meet most of the increase in domestic U.S. demand and exports through 2025. And given that U.S. gas demand is barely growing – in part because it is in a knife fight with renewable energy in markets such as Texas and California – exports are key:

Notice that the growth in LNG exports drops off after 2020. That’s because, after the initial wave of new export capacity has opened up, there’s a gap because new projects haven’t yet received a final investment decision. Given that it takes three to four years to build a new terminal, those decisions need to be made soon if exports are to grow appreciably in the early 2020s.

Guess what could really bother an energy executive contemplating taking the plunge on a multi-billion-dollar investment in a facility built for the sole purpose of international trade? And guess what could really bother a potential trade partner thinking about maybe signing a 20-year contract with said facility?

Tariffs aren’t likely to derail U.S. LNG exports in the near term, as cargoes can be switched elsewhere to a degree. But if this trade war is extended, then the combination of lower margins, likely lower utilization of terminals and the shadow hanging over trade policy in general is a strong deterrent to anyone thinking of financing or contracting with new U.S. capacity. China is, after all, expected to account for almost half the growth in global LNG demand over the next five years, and a fifth through 2030.

In weighing on U.S. competitiveness, tariffs would also encourage rival producers to invest in new capacity. “If Qatar had any doubts about expanding, they won’t now,” says Marianne Kah, a former chief economist of ConocoPhillips, now on the advisory board of the Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy.

We are currently witnessing a temporary slowdown in oil-production growth from the Permian basin due to inadequate oil pipeline capacity. But that could drag on far longer if there’s no place for excess gas to go. The old option of flaring it and providing a Texan light show for astronauts is no longer tenable.

Tariffs, born of a policy of dominance, may ultimately stymie that for America’s gas producers. Just remember many of them also happen to pump out another product for which, similarly, dreams of dominance could backfire.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal’s Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times’ Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

© 2018 Bloomberg L.P

Join The Club

Join The Club