Carr: Searching the Bottom of Long Island Sound

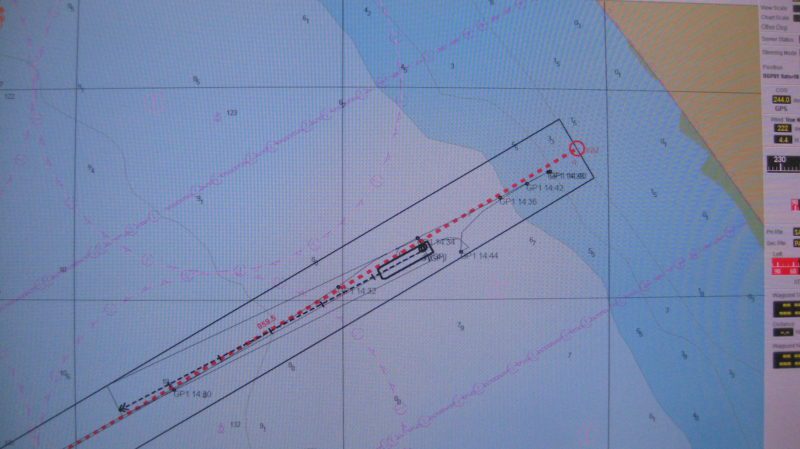

By Michael Carr – We were searching the bottom of Long Island Sound between Old Saybrook CT and Plum Island Long Island, for a 36 ft. powerboat. The boat sank...

Updated: February 28, 2019 (Originally published January 12, 2019)

By Michael Carr – He was hard aground on the Silver Strand Beach at Coronado Island CA. Well, not just himself, but also his 315-foot ship and 32 Soldier crew. They had plowed right up on the beach while making way at 1.5 knots. He could feel the LSV 3 going aground, and it felt awesome! It was a beautiful Sunday morning, the sun was just coming up, there was thin fog over San Diego, and all you could hear were seagulls and surf. Just amazing.

This event, running aground on an unimproved beach, would be a career-ending event for a Naval, Coast Guard, or Merchant Mariner, but for an Army Mariner this was an accomplishment to be thoroughly enjoyed. Running landing craft up on beaches is what they train to do, and is an act which takes more attention and precision than one might expect.

You cannot just point toward a beach and run up on it. That might lead to broaching in the surf, or grounding too soon if the depth is not calculated properly. Beaching with excessive speed prevents, or severely inhibits, retraction. And difficulty retracting leads again to broaching. Recovering from being broached on a beach is almost impossible. Energy from breaking surf just keeps pushing you sideways up the beach.

When you beach an Army landing craft it must be done keeping your vessel perpendicular to the incoming waves, not perpendicular to the beach. Waves and surf do not always impact a beach parallel to its shore. Because of differences and changes in depth, and the beach’s topography (Straight or curved or both?) waves refract and come in at differing angles. You must study the chart and peer at the beach through binoculars to assess the true nature of the surf.

This is often difficult from offshore, since you can only see the backside of the waves and surf, not the more revealing front side, which can only be seen when you stand on the beach itself. You must focus on what you can see from the backside, and visualize how these waves are actually breaking. Building this skill takes years, and requires going to various beaches, and watching waves, under differing conditions coming in & breaking. Most people go to beaches to relax, but many Army skippers go to the beach to study the waves. How would I land my LSV or LCU under these conditions? Could I do this at night?

Army landing craft are equipped with stern anchors. These anchors use steel cable, not chain, for rode and paid out as the landing craft approaches a beach. This is a tricky operation. You must drop the anchor when close to the beach, but not too close. There is limited wire on the spool for the stern anchor, so you need to plan the point at which to drop the anchor, ensuring there is sufficient cable to pay out so you can reach the beach.

Unlike dropping an anchor with chain, where you call out “Let Fall” and away goes the anchor and chain in free fall, a stern anchor is paid out from a drum, which has a maximum speed. Your vessel’s speed needs to match the speed at which the stern anchor’s cable is being spun off the drum.

This requires a coordinated effort by the stern anchor drum operator, usually the Chief Engineer, and the Deck Officer, most often the Vessel Master. Here is how the conversation usually goes:

“Bridge to Winch, drop the stern anchor and let me know when the anchor is on the bottom and how the cable is tending.”

“Bridge, this is winch, anchor is away and cable paying out at 12:00 o’clock” (Note: directly astern is 12:00 o’clock, with 3 o’clock being 90 degrees to port, and 9 o’clock being 90 degrees to starboard).

“How is cable tending now?”

“Cable is at one o’clock and tending down 45 degrees, moderate strain.”

Constant chatter back forth from bridge to stern anchor while driving forward is necessary. You cannot back down, far to risky since you could suck the stern anchor’s steel cable into the props or around a rudder. Forward speed needs to be adjusted, clutching engines in and out of gear.

“Both engines, Ahead dead slow”

“Both engines, all stop”

“Port engine, ahead slow”

“Port engine, stop”

Constant adjustment to speed and heading are required to keep your vessel maneuverable, and not losing steerage. Stay perpendicular to the incoming swells and surf. Slight port and starboard adjustments can be made using the bow thruster, but this must be done carefully, not pushing the bow too far off left or right.

Slow, steady, always forward.

You must hit the beach with sufficient speed to actually ground out and make enough contact to hold your position, but too much speed pushes you too far up on the beach, risking the possibility of not being able to retract.

You can tell when you make contact with the beach, your boat motion changes, there is no more rolling, and the bow imperceptivity rises. You can feel your speed slowing and then, you are stopped. At this point you call the stern anchor.

“Stern anchor, bridge. We are on the beach, take a strain on the stern anchor. Let me know if it is holding.”

It is important to know if the stern anchor is dug in and holding, or if it is just dragging across the bottom. It you have not provided sufficient scope, the anchor can drag and will provide no help in retracting. If the anchor does not hold you must monitor the stern cable and ensure it does not tend under the boat, and then retrieve the cable and anchor expeditiously when you retract, without allowing it to tend under your stern.

If it does hold, then it will help greatly when you retract, providing a force to pull you off the beach, helping to break bottom friction and guiding you back the way you came. However, when backing off after lying on a beach you must apply sufficient backing force from your engines to stir up the sand and break friction. As soon as you break friction you must immediately back off the power, otherwise you will slingshot backwards, and overrun your stern cable. Bad things happen when you come off a beach too fast.

But on the other hand, you cannot be timid when retracting. You must expeditiously back off the beach and turn your vessel around as soon as you are seaward of the surf zone. Turn when you have sea room and you are able to re-stow the stern anchor, and then head to sea.

You might beach for only a few minutes, or you might sit on a beach for hours or days. Conditions can change so there needs to be a continuous monitoring of winds, seas, & tides. Landing and retracting properly at the designated point on a beach is a true accomplishment, reflecting teamwork, seamanship and skill.

Back on the Silver Strand that quiet Sunday morning there were many smiling Soldiers on the LSV 3, they had executed a skill, which Soldiers work years to learn and perfect. Land your vessel on unimproved beach, discharge and/or load cargo, and retract flawlessly. And do this time after time. This is what the Army’s motto “Across the Beach” exemplifies.

Sign up for gCaptain’s newsletter and never miss an update

Subscribe to gCaptain Daily and stay informed with the latest global maritime and offshore news

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up