Piracy Reporting Centre: Singapore Straits Emerge as Piracy Hotspot

Global piracy and armed robbery incidents against ships have risen sharply in the first quarter of 2025, with a notable 35% increase compared to the same period last year. The...

By gCaptain Staff

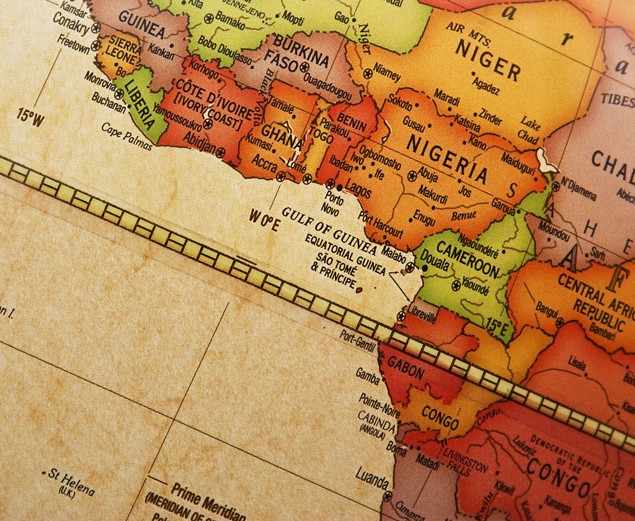

US interests in the Gulf of Guinea region including maritime shipping, safety of American citizens, and energy resources are becoming increasingly affected by piracy and maritime crime, an issue that continues to expand in both rate of attacks and scope.

Ties between pirates and transnational criminal and terrorist organizations indicate both a likelihood of more sophisticated attacks and funding of transnational criminal and terrorist endeavors.

Background

Nigeria is reemerging as the epicenter of maritime crime. Data from the Office of US Naval Intelligence indicates 64 incidents of hijackings, kidnappings, unauthorized boardings or vessel attacks have occurred in the Gulf of Guinea from January until August 2013. According to International Maritime Bureau figures, the Gulf of Guinea has overtaken Somalia as the world’s hotspot for piracy.

Further, the threat is shifting both in terms of targets and scope. Gulf of Guinea piracy traces its roots to the oil boom of the 1970s, reflecting simple economic opportunism. Docked ships or those at anchor were robbed and bunkered, as oil theft is commonly known in Nigeria. By the early 2000s, piracy became politically motivated, stemming from inequitable distribution of Nigeria’s petroleum wealth. The most powerful militant group that emerged was the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND).

From 2000 to 2005, Nigeria’s waters were more pirate-prone than those off Somalia. Intensified naval patrols and a 2009 government amnesty offered to Delta militants resulted in a decline in reported attacks – from a high of 42 in 2007 to 10 in 2011. Yet the period from 2011 to present has witnessed a surge in piracy as Nigerian gangs have expanded their reach to regional waters and received backing from transnational organizations. Unlike the Somali piracy model, in which entire ships and crews are held pending ransom negotiations, Gulf of Guinea attacks are more likely to take valuable (ie Western nationality) crew members, personal possessions and cargo, then abandon the ship and other crew due to lack of a safe port for holding the vessels. Crude oil is often transported from the hijacked vessel to a supply ship waiting to transfer the product to the black market.

The recent attack off Togo on M/V Liberty Grace, a US-flagged bulk carrier with 22 personnel onboard (including two US Merchant Marine Academy cadets), highlights the increasingly brazen acts and the shift from previously targeting only ships involved in the oil industry. This broadened scope and reach indicates growing capabilities and coordination of pirates. It also marks the first US-flagged vessel targeted in at least a year.

International piracy figures – underreported due to concerns for hostages, insurance and ransom payments – show a dramatic rise of kidnappings, with 30 crew kidnapped in the first half of 2013, as compared with 3 in 2012.

Strategic Interests

The West Africa nations of Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Angola, and Gabon are a major source for oil, cocoa and metals. Nigeria is a top producer of crude oil, with an estimated output of 2 million barrels per day of high-quality light, sweet crude. Nearly 33% of Nigerian oil exports head to the US, comprising approximately 10% of US oil imports. The US is Nigeria’s largest export partner, accounting for nearly 17%.

A study by advocacy group Oceans Beyond Piracy estimated piracy in the Gulf of Guinea cost the world economy between $740 million and $950 million last year and the cost is expected to rise in 2013. A report from Yaounde-II University in Cameroon suggests the figures may be much higher, at $2 billion. Further, insurance companies have noted the danger of the region and are raising rates significantly for ships transiting the region.

Piracy links in Western Africa may have broader implications for global security. Unlike Somali pirates, the Nigerian gangs are increasingly connected to transnational networks. Bunkering of hijacked vessels is now feeding into Lebanese and Eastern European criminal interests, who reportedly arrange black market sales of stolen crude and refined cargos.

Shipping industry guidelines recognize that recent attacks appear have had significant planning, with ships transporting valuable products targeted in well-coordinated and executed operations. There is growing concern that finances obtained through piracy fund terrorist activity conducted throughout Africa by Islamist extremist groups, particularly those operating in the Sahel desert region, such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar Al Dine and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa. There are indications of ties between Nigeria-based Boko Haram and AQIM, raising concerns on terrorism.

Further, gangs and the corruption within the government that facilitates the black market trading serve as a destabilizing factor for Nigeria.

As Africa’s most populous nation and one of the world’s largest oil producers, the Nigerian economy is driven by the oil sector. Nigeria acts as an important regional security stabilizer due to its economic stature and contributions to regional and global peacekeeping. Already at a delicate balance due to ethnic and religious tensions, further destabilization in Nigeria could have a catalyst impact for the region.

Regional Response

Unlike the international response to Horn of Africa piracy, responses to attacks in the Gulf of Guinea are far more limited. Maritime and shipping companies are often left to negotiate for release of their employees through undisclosed ransom payments. Regional inter-governmental response is limited primarily to security meetings. A June 24-25 summit in Yaounde, Cameroon saw representatives from the Economic Community of Western African States, the Economic Community of Central African States and the Gulf of Guinea Commission draft a code of conduct. This attempt to address piracy has been signed by 22 states.

A central problem of piracy stems from both a lack of commitment to prosecute criminal actors and a lack of regional maritime security capacity. Nigeria is the sole nation possessing either aerial surveillance or patrol craft capable of interdiction at sea, yet has difficulty employing assets in a coordinated manner to impact piracy. At any given time, it is estimated that up to 75% of its fleet is not operational.

Regionally, naval capacity is poor. Further, a key component of success against Somali pirates, armed Private Security Teams (PST), has been hampered by national laws preventing armed guards aboard ships operating in the region’s territorial waters.

Next Steps

Through Africa Command, the US military conducts joint training exercises with West African navies to “enhance regional and maritime security and safety by assisting African nations in developing proficiencies in areas such as maritime interdiction operations, search and rescue operations, counterterrorism, and overfishing of African waters.” Joint training often occurs aboard US Navy ships and through Africa Partnership Station. Increased training with regional navies – more akin to coast guards – will improve counter-piracy skills and maritime security capabilities. Greater steps must be taken by the international community to address piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, as regional capacity to stop it does not exist.

Further, after reviewing lax port security measures, the US government, through its Embassy in Lagos, has cautioned the Nigerian government to improve its ports security system within 90 days (August deadline) or face the stoppage of sail of vessels to Nigeria. This highlights the multitude of security problems in the area that must be resolved through a ‘whole of government’ approach.

1 Per U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence.

2 U.S. Energy Information Administration; CIA World Factbook. “Nigeria”

3 According to IISS Military Balance for 2007 the Nigerian Navy’s operational forces included one MEKO 360 class frigate, NNS Aradu; one Vosper corvette, Enymiri (F 83); two modified Italian Lerici class coastal minesweepers (commissioned in 1987 and 1988); three French Combattante fast missile craft; and four Balsam ocean patrol craft (ex buoy tenders). All vessels are listed as having their serviceability in doubt. www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/nigeria/navy.htm

Sign up for gCaptain’s newsletter and never miss an update

Subscribe to gCaptain Daily and stay informed with the latest global maritime and offshore news

Stay informed with the latest maritime and offshore news, delivered daily straight to your inbox

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up