By Kendra Pierre-Louis

(Bloomberg) –The world’s oceans are simmering. Some 48% of the ocean experienced marine heat waves in August, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, adding to the hottest year for oceans since record-keeping began in 1991. The heat could be felt from the UK, where coastal waters were as much 9F (5C) warmer than usual, to Florida, where the Atlantic pushed into the high 90s F (around 35C).

“The most staggering thing over my career of 30 years as a researcher, is that the things I thought were coming in 50 or 100 years, they’re here now,” says Alistair Hobday, a biological oceanographer and a research scientist at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia’s national science agency. “Heat waves are one of those. And I think of heat waves as if they’re an alarm bell. Surely people listen to an alarm.”

Hobday has spent years analyzing data to understand climate change’s impact on oceans, including temperatures. His research has found that marine heat waves threaten global biodiversity, which in turn imperils everything from fisheries to food security and tourism. In 2018, Hobday co-authored a study in Nature Communications that identified a 54% increase in marine heat wave days between 1925 and 2016 due to climate change.

More recently, CSIRO and other research groups have started to develop ways to predict certain marine heat waves, the kind that result from the movement of ocean water versus changes in the atmosphere. “Where communities are prepared, impacts can be mitigated, at least partially,” Hobday wrote in the journal Nature this week. “This depends on knowing which regions are most likely to be affected.”

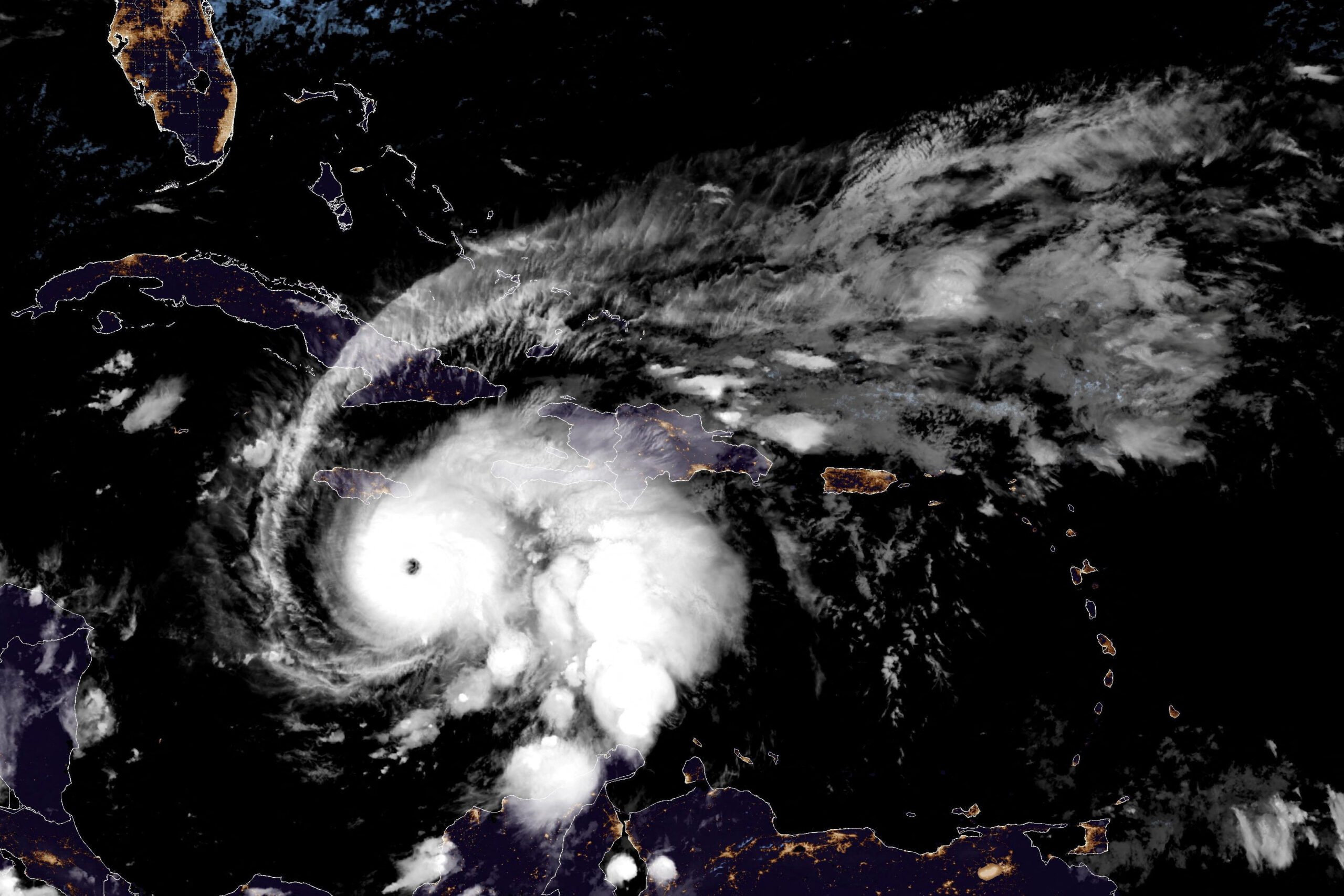

The urgency of the threat is also why Hobday has advocated for naming marine heat waves like hurricanes. Spain’s Seville is among few places with a process for naming heat waves on land, but people “don’t have a good sense of location in the ocean,” Hobday says. “Giving them a name also improves ocean literacy, and I think it helps build a connection to an event. Giving events a name helps them translate into the human experience.”

Bloomberg Green spoke to Hobday about how marine heat works and what impacts to watch for.

This conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

What is a heat wave in the ocean?

A marine heat wave lasts for more than five days, and [occurs when] temperatures are in the 10% most extreme ever seen for that location. It’s not an absolute threshold. In some parts of the world that will be two degrees above average, in some parts of the world, it will only be one degree above average. In some parts, it might be five degrees, depending on how much variability you get.

Heat waves are longer lasting in water because water retains heat for longer than air. And they can lead to mass mortality of animals. In the short term, if you’re a fish or a dolphin, you just swim somewhere else. But as the heat waves get longer and bigger, things like tuna and sharks won’t be able to swim fast enough to get to cool waters because as water warms up, it holds less oxygen. So as they need to swim faster, they’re finding it harder to breathe.

It sounds a little bit like someone who is adapted to sea level trying to run in high altitudes.

That’s a great analogy. A heat wave basically takes you from sea level to high altitude and says, “Away you go, start running your marathon.” It’s hard work.

What about the impact on species like coral?

They’ve only got a short window of time where they can survive these stressful events. As the heat wave goes on, everything that can’t move — kelp, coral, seagrass — goes locally extinct.

When you get warmer waters for a long period of time, we can also have disease outbreaks because diseases do better in warmer water. We also have harmful algal blooms that occur in longer heat waves, and they can make things like domoic acid and paralytic shellfish poisoning more prevalent. Humans can die from eating shellfish tainted with domoic acid; so can seabirds and seals. I’ve seen videos of them basically lying on the beach twitching right before they die. It looks like a pretty horrible way to go.

All of that leads to mass die-offs and the longer and bigger the heat wave goes, the more extreme the die-offs, the more the food web is affected. That leads to fisheries being closed [and] loss of industries. These marine heat waves are a look into our future and if you don’t like what that future looks like, get active.

Speaking of the future, increasingly researchers can predict marine heat waves?

There are a couple of groups around the world that do long-term forecasting of marine heat waves, and that’s looking two or three or even four months ahead of time to where we expect these events to occur. My group in Hobart is using both machine learning and ocean models — two methods — to have a look at where we expect heat waves to be three-or-so months ahead of time.

We can predict the big marine heat wave events where it’s due to ocean water moving around. The Blob [off of the Pacific Coast] was predictable. The Atlantic marine heat wave was predictable. The Caribbean marine heat wave was a combination of both ocean water moving around and a hot atmosphere. But we saw that there was going to be at least a strong event, it turned into an extreme one because it got cooked by the atmosphere

We’re still in the testing phase, but we’re very close to having them included like a weather forecast on the internet, a marine heat wave forecast.

What’s the benefit of this kind of long-range forecasting?

It will take away the element of surprise for businesses, which will help them navigate these risky events. Maine lobster, for example, might decide to set up different purchasing arrangements with the Canadian importers, because Canada and Maine lobster fisheries are a bit out of phase [lobster season, absent climate change, in Canada tends to start a bit earlier and end sooner than in Maine]. The heat wave means that they start to overlap each other, which leads to excess product in the market and prices going down. If you knew that was coming, you might manage your business differently.

If you’re doing a restoration project, like the mangroves or seagrass or kelp, maybe you halt that until after the heat wave.

For bushfires, if we know an area’s going to be burning, people are now taking protected fish species out of rivers in Australia, putting them into captivity for a period because after the bushfire, all the ash washes into the river and it will kill all the fish. For marine heat waves, we might take seagrass seeds from an area before the heat wave and make sure we’ve got those ready to put back into that particular area of restoration after the heat wave. If we have warning about the future, we can do a bunch of things differently.

As Australia heads into summer, what are you predicting for the Great Barrier Reef?

We’re predicting marine heat waves for the Great Barrier Reef this summer, which will be a real downer. It’s likely the Great Barrier Reef will bleach again this year. It gets me down. It’s an icon of Australia. It’s part of our national identity.

© 2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Editorial Standards · Corrections · About gCaptain

This article contains reporting from Bloomberg, published under license.

Join The Club

Join The Club