By Peter Apps

LONDON, May 26 (Reuters) – In late April, trucks with number plates from Russian-occupied Crimea descended on the southern Ukrainian city of Melitopol, emblazoned with the letter “Z”. According to local mayor Ivan Fedorov, the convoy – filmed and shown on social media platform Telegram – carried grain seized by Russian forces from silos around the town.

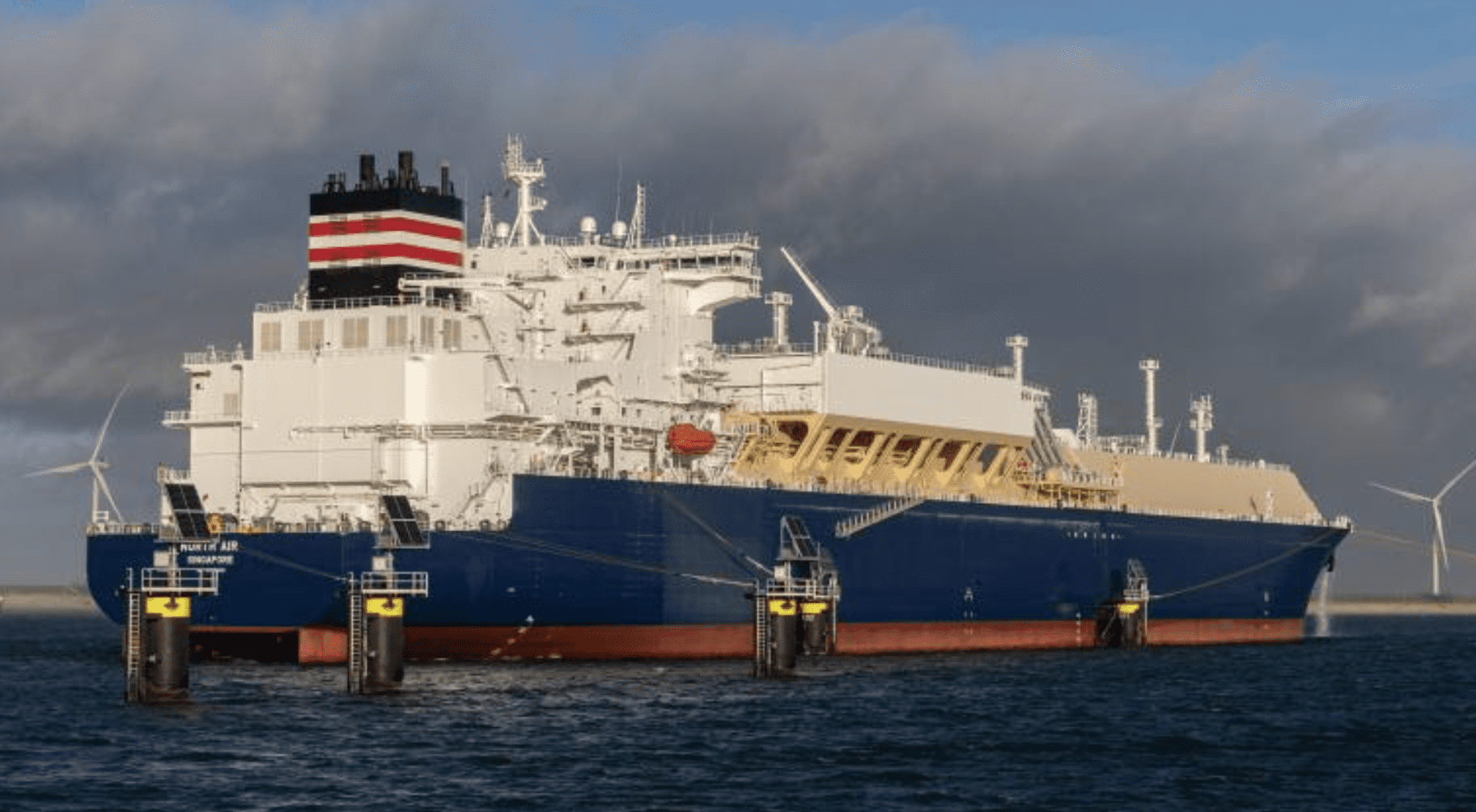

Exactly where it was then taken is unclear. Images from satellite firm Maxar of the Crimean port of Sevastopol, however, have shown two Russian bulk carriers – the Matros Pozynich and the Matros Koshska – loading alongside grain silos on May 18-19 before sailing, most likely to Russia’s ally Syria.

Ukrainian officials say both sets of images are proof of mass looting of grain reserves from areas seized by Russia since its Feb. 24 invasion, alongside what Ukrainian and Western officials say has also been deliberate targeting of Ukrainian agricultural infrastructure and a blockade of its ports that has produced a global food crisis.

Three months in, the war is not just brutal tank and artillery contests in the disputed Donbas regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. It has become a much larger economic and strategic confrontation, upending long-established worldwide supply lines and industries that have become battlegrounds in a way a globalized economy is struggling to deal with.

Last year, Ukraine fed around 400 million people worldwide, according to the World Food Programme, with Ukraine and Russia between them the main source of sustenance for much of the Middle East and Africa. Both shipped much of that food through Black Sea ports – and aside from the handful of Russian shipments to Syria, that has largely ceased.

With Ukraine’s main harvesting season now just around the corner, what happens in the coming months will have profound implications for households and the global economy. In Ukrainian and Russian-controlled areas alike, there is a frantic race to clear silos of at least 21 million tonnes of last season’s grain so the new crop can take its place.

FOOD CRISIS HARDENS RHETORIC

That may be a challenge. Ukraine normally exports 6 million tonnes of grain a month by sea, and is managing barely 1-1.5 million by rail. Harvesting of spring crops has already been sharply limited in the country’s war-torn east, while attacks, fuel shortages and the exodus of millions of Ukrainians will also hit production.

Rhetoric is hardening on all sides. At Davos on Tuesday, European Commission President Ursula von den Leyon called on Russia to unblock the Black Sea, echoing comments by U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken last week in which he accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of holding world food supplies “hostage”.

This week saw the Netherlands agree to provide U.S.-made Harpoon anti-ship missiles to Ukraine, with Western concerns over the growing food crisis an explicit justification for upgrading Kyiv’s ability to hit Russian vessels.

One suggested plan – being pushed by the Baltic states of Estonia and Lithuania, as well as by some former Ukrainian officials in the West – would see NATO warships enter the Black Sea to escort food cargoes from the Ukrainian port of Odesa, potentially putting them in direct confrontation with Russian forces enforcing a de facto blockade.

That prompted a furious reaction from Russian state media on Tuesday, warning that such action risked nuclear war.

Who finally retains access and control to those key Black Sea ports is of increasing importance – and will be vital to any final peace negotiations.

BLACK SEA SUPPLY LINES

Last month, Russia’s military said Moscow aimed to take control of Ukraine’s entire Black Sea coast from Donbas through to neighboring Moldova’s separatist Transnistria region. That would devastate Ukraine’s economy, although Russia currently lacks the military ability to do so quickly.

But Moscow’s forces are inching forward in the Donbas, while the Kremlin fast tracks Russian citizenship for areas it controls – including the key grain-producing regions around Melitopol and Kherson, the latter a major rail hub for the still government-controlled Odesa.

Ukraine and some of its allies, meanwhile say they want Russia swept from all the territory it has seized since 2014, which would include Crimea and Sevastopol, home of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. That might safeguard Ukraine’s exports in perpetuity – but it would also be viewed a strategic catastrophe by the Kremlin, likely producing new atomic threats.

For now, getting Ukrainian food supplies out through Poland and mainland European states requires transferring them from wider Soviet rail gauge wagons to those of the narrower width used by the rest of Europe. There is talk of shipping goods to Baltic ports in Latvia and Lithuania – but while that would avoid the need to leave the former Soviet rail system and transfer goods to new trucks, it requires support from Kremlin ally Belarus.

Russia, meanwhile, is successfully getting much of its grain onto the international export market, particularly to Africa, the Middle East and Asia – although as with its fuel exports, it is having to sell at a discount because of Western sanctions. That is not enough, however, to stop global fuel and food prices rocketing, with a potential further crunch later in the year.

Nor is that the only challenge. The massive Azovstal plant in Mariupol – now largely destroyed and captured by Russian forces – was one of the largest producers of noble gases such as xenon, argon and neon, the latter vital for the production of microprocessors chips. If Russia can restart production, that would put almost all of production of these gases in the hands of Moscow and Beijing, giving them yet another stranglehold.

Little surprise, therefore, that this week at Davos NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg was arguing that Western freedom and democracy were more important than globalized free-trade, urging Western nations to build new infrastructure and resiliency.

The coming winter will challenge that – particularly if much of Ukraine’s harvest has been lost, planting restricted, the Black Sea still blocked and Russian energy supplies to Europe curtailed before new renewable and nuclear sources come online. That may hit the world’s poorest hardest and divide the West – and however that plays out, it will shape the post-war world.

*** Peter Apps is a writer on international affairs, globalization, conflict and other issues. He is the founder and executive director of the Project for Study of the 21st Century; PS21, a non-national, non-partisan, non-ideological think tank. Paralyzed by a war-zone car crash in 2006, he also blogs about his disability and other topics. He was previously a reporter for Reuters and continues to be paid by Thomson Reuters. Since 2016, he has been a member of the British Army Reserve and the UK Labour Party. (Editing by Tomasz Janowski)

(c) Copyright Thomson Reuters 2022.

Sign up for our newsletter

Join The Club

Join The Club