For your Sunday morning reading we bring you a top post from the gCaptain archives. Enjoy!

How Do Mariners Pay For Training?

By Leonard Lambert

Since the inception of STCW ‘95 on February 1st of 2002, the training and certification of mariners has become more streamlined. The heart of the certification process is multiple training schools spanning the country which offer specific classes catered to each mariner’s needs, from AB to unlimited tonnage Master. Schools now provide USCG approved comprehensive programs that increase efficiency to the licensing and documentation process. Mariners have resources that only a few years ago were not available to them. These training schools offer valuable solutions to the dynamic regulations of the USCG licensing process and the education programs fulfill all the required training a mariner needs to obtain that final goal…a license and Merchant Mariner’s Document (MMD).

Increased regulatory training has led to higher training costs. Mariners who are completing large portions of training; including class time, practical assessments, sea time, formal tests, simulator training and group presentations find the cost of obtaining a Coast Guard unlimited tonnage deck officer’s license staggering.

“Out of pocket” up front financing by an individual mariner can be so expensive, mariners struggle to make payments while supporting families, working and having any money or time left over. For example, Basic Shiphandling costs $2895.00 (Maritime Professional Training, Ft. Lauderdale Class Schedule 2009). It is a 5 day course and only one of about 20 classes consuming approximately six months to complete the upgrade from AB to a licensed mate and receive the STCW “Officer in charge of a Navigational Watch.”

Tuition alone for an officer’s license can total up to $20,000. That does not include the “soft cost” living expenses mariners must continue to maintain while training and not working. Lower tonnage, inland water master and mate licenses and MMD’s are not quite as expensive or time consuming, but they still require money, time and dedication. Mariners seeking an entry level Ordinary Seaman (OS) or Able Bodied Seaman (AB) will find it even less expensive and time consuming. The big ticket prices are for the upgrade to an officer. So, the inevitable question is: How does a mariner pay for training?

There are multiple avenues to gain financing for these endeavors. The most important point is: The mariner (student) MUST have the correct expectation for exactly what a company, labor union, finance company, or the U.S. government will do regarding financial aid and, in return, what is required of the mariner to fulfill the end of that bargain. I cannot stress this enough: Misunderstood expectations will lead to frustration, expense and ultimate failure for both the mariner and employer.

Working for a Company

If you are a mariner, licensed or unlicensed, that works directly for a shipping company without union representation, the first line of financing is through that company. Mariners could undergo a “probationary” period of employment (it is a trial period to see if there is a good fit for a career). This pre-requisite needs to be cleared in advance, if the mariner needs the costly training. Every day of credit onboard a vessel or with a company matters, probationary or not, and it is the mariner’s duty to fulfill the requirements the company has set forth for financing. For example, a U.S. tanker company has a policy that before it pays for any mariner’s training, the mariner MUST complete one year of employment.

Companies can also mandate that the mariner pay for all the classes up front and then reimburse only after the mariner has successfully completed ALL CLASSES. That means that there better be some serious planning involved if the mariner is not going to see a dime of money from the company until the program is completed and the license in hand. Multiple financial aid avenues must be employed to reach that end goal of re-imbursement and a letter of intent from the employer agreeing to employ the mariner after successful completion of the training should be in place. This style of financing is rare given the heavy cost to the mariner. Most companies have become privy to this and changed their policy so mariners can be reimbursed as they take each class or block of classes. Companies will require copies of those certificates and will have class enrollment sent to them to monitor the mariner’s progress.

Beware that companies may only reimburse up to a certain percentage of the cost. Meaning, the mariner could have to pay for room and board, travel to and from the school, study guides and software and a percentage of the tuition. Again, this is very important for the mariner to figure out with their company before taking on a commitment like this. Clear expectations set ahead of time will lead to successful completion with minimal cost. When I finally received my 3rd mate’s license, the total cost was $25,000. I paid, out of my own pocket, only $6,000. The rest was paid by unions, companies and government organizations. None of which I had to pay back.

Currently, many companies have the mariner sign a letter or “contract of commitment” for a specified period of employment to follow the completion of training and the issuance of the mariner’s new license. Companies want to see a return on their investment by locking the mariner into a career within the company. It is one way to foster good people to stay on vessels and it is a great move for mariners looking for a steady job with upward promotions. The more the company will pay the more return they could want. If a company is not giving the monetary benefits equal to the time commitment, the mariner must try to re-negotiate a better deal. Find out what other companies are doing to strengthen the argument; it can’t hurt to try to improve the financial situation.

Unfortunately, training benefits offered through a company program can be strictly performance based or require other qualifications be met. For example, a U.S. shipping company “awards” its officers and crew a training program that is based on performance levels. Each level has a fixed amount of tuition reimbursement the company will offer. So, the better a mariner does on the vessel, the more training benefits received.

Some companies provide training in-house for their employees. In house training is especially relevant if the vessels require specialized training like tankers or U.S. government vessels. As a company employee, make sure this in-house training is approved by the Coast Guard for a license or MMD. This should be printed on the training certificate itself, and the training facility should be listed on the Coast Guard’s approval Website http://www.uscg.mil/nmc/mmic_appcourses.asp .

A company may have established contracts with certain schools to provide the Coast Guard training, so the mariner might have no choice on the school or its location. It is very likely that a company has their vessel in one area of the world and the company office or headquarters in another meaning the mariner might have a perfectly fine training school in his/her hometown or near their vessel, but must travel to a school designated by the company that is close to neither. As a mariner and an employee, know the schools the company has relationships with before entering into the training commitment. There are many variables involved, as all companies and vessels are different.

Working for a Union

The maritime unions provide shipping companies with licensed officers and unlicensed crew. Maritime unions provide training to their members through their own training schools across the country. These schools are of great benefit to the members who are advancing. Like companies, unions will have prerequisites for allowing members to attend classes at their school. The members, who take advantage of this training could get room, board and travel to and from the school. Some unions will pay their members a daily student rate while they are at school. Training is a very large benefit that unions have for their members. The training matrix differs from union to union and it is the member’s responsibility to get the correct information from the union so the expectation is met. The basic question remains the same: How much time is needed to qualify for training? Like companies’ employment contracts, some unions can also require a certain amount of time spent in the union after the training has been completed. If you are a union member, enroll as soon as you qualify for schooling. The time spent at that union’s school can also count toward seniority in the union or pension credit.

An example of unions schools are the Paul Haul Center for Maritime Training and Education located in Piney Point, Maryland, which is the training center for the Seafarer’s International Union (SIU). The International Organization of Masters, Mates and Pilots union (IOMMP) has a training school in Linthicum Heights, Maryland called the Maritime Institute of Technology and Graduate Studies (MITAGS) and The Pacific Maritime Institute in Seattle, Washington. For licensed engineers and deck officers in the Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (MEBA) the Calhoon M.E.B.A Engineering School located in Easton, Maryland is their training school. The American Maritime Officer’s Union (AMO) has the S.T.A.R. Center located in Dania Beach, Florida and Toledo, Ohio. These are a few of the schools owned and operated by maritime unions and they are major proponents of maritime training in the U.S.

These schools are open to all students, so as a union member, the mariner might be sitting next to someone from a company or another union who is just trying to get the classes needed on a schedule that fits. If there is room in the classes, the school will fill them with students, regardless of where they came from or who they work for. This can be difficult for a union member, as the classes can fill up with non-union students based on the demand.

If a union member needs to take classes from schools other than the union training facility (i.e. specialized military, tank ship or government training) or due to schedule conflicts at the school, unions can categorize this as “offsite” training. This training can be covered at a full or reduced rate, or at a per diem rate, depending on the union. It is important for the union member to find out what is covered and what is not covered so the expectation is set before the mariner takes the “offsite” training. Discuss these topics with your union training representative to ensure no surprises.

Some union members have permanent jobs with shipping companies. These mariners have the benefit of combining union training with company training. Any classes needed for those mariners that are not paid for by their union, can be picked up by the company’s training fund upon company approval.

There are a number of other maritime training schools which are not affiliated with unions. Each school has training classes available and they are located all over the country. If a mariner has a choice in schools, the Coast Guard Website has a list of all the schools in the country and what each one is specifically approved to teach.

Financial Aid

If neither company nor union funds are at a mariner’s disposal, do not fret. There are state and federal programs in place to pay for training. These programs provide opportunities for citizens to be trained and placed in good paying jobs. In my opinion, there is no better component of the American workforce that fits into this category than the U.S. Merchant Marines. The length, cost, and difficulty of training needed to advance are immense. If these programs can help American workers to obtain the goal of getting a license or MMD and into a job, the programs are a success and will continue.

The challenge in obtaining any federal grants for training can be broken down into 3 simple categories:

1. The current job you are in is shrinking or becoming obsolete. When International farm-raised salmon flooded the U.S. market, Alaskan fisherman felt an economic stranglehold as the price of fish plummeted. In response to the increasing number of unemployed fisherman in Alaska, a state and federal program was created. It paid for fisherman to receive their STCW, Coast Guard officer’s license or MMD and placed them in jobs throughout the U.S. Merchant Marine. It has been a great success and still continues to fund students who need training for a better job. Similar industries have suffered this kind of downturn and can qualify for state and federal re-training funds. Programs like Washington State’s Worksource is an example of a employment resource that helps citizens who quality to be trained and licensed in different occupations. I personally received $3,500.00 to put towards my tuition. These state programs are usually available through the labor/employment development departments.

2. The new job you want requires training/licensing to get. The Coast Guard mandates that every mariner complete certain training for whatever position they want. A mariner cannot get a job on a ship without fulfilling certain training requirements and those requirements are available on the CG Website.

3. After completing the training, there are jobs available in your new field. Because the training requirements are mandatory and lengthy, the employment rate for mariners is quite good and can be proven on most maritime employment Websites.

The key to getting state and federal money is research. Mariners must research what employment training programs are available to them by city, state, county and country and what specific requirements mariners need to fulfill to obtain the money. This can be done through employment programs such as unemployment insurance, employment education departments, maritime school’s administration and maritime academies.

Resources are also available through scholarships from corporations, family heritage, businesses and unions, all of which have pre-requisites for the mariner to complete. For example, the scholarships may only apply to certain schools, or the money might have a time limit the mariner must complete the training or the money gets recycled back to the next candidate. Be clear on all guidelines regarding free money once it is gone it is extremely hard to get back. These employment programs have strict rules which the mariner has to follow.

This type of financing can bridge a gap between a mariner finishing the training, or running out of money, becoming frustrated and quitting the program. Major maritime schools have financial aid available through accredited programs like Stafford assisted and unassisted student loans and Freddie Mac/Fannie Mae lines of credit.

Finally, if the mariner does have to pay out of pocket for any training, make sure all avenues have been tried. Leave no stone unturned when obtaining financing. This can be in the form of family loans; hit up that rich aunt or uncle of yours. Tell them your plan, how you are going to execute it, and the payment process. Most likely, that is how they got rich themselves: had a plan and executed it.

As a last resort, lines of credit from a traditional bank on real estate, autos, or any asset can be used. I recommend this form of credit (credit cards) as a LAST and FINAL resort. But if this is the only way to complete the process, here are some guidelines. Plan ahead for debt management; know how much the entire process will cost including living expenses and have a schedule that reflects realistic costs (if it is not feasible to take all training at once, break it into sections). Set up payment plans immediately following receipt of your new license or MMD and pay as much as you can afford quickly.

If a mariner pays any money out of pocket for training, there is a tax deduction benefit included. Talk to schools and tax advisors about the benefits mariners receive for travel, food, tuition, books, etc. that can qualify for these very important tax deductions. As training becomes more expensive, take the time to pursue all options available. It is the mariners themselves who will benefit the most from researching all available means of financing and it will greatly reduce the hardship of obtaining a Coast Guard Deck Officer’s License. I know it did for me.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leonard Lambert is the author of THE NEW HAWSEPIPE, published by Cornell Maritime Press.

Leonard Lambert is the author of THE NEW HAWSEPIPE, published by Cornell Maritime Press.

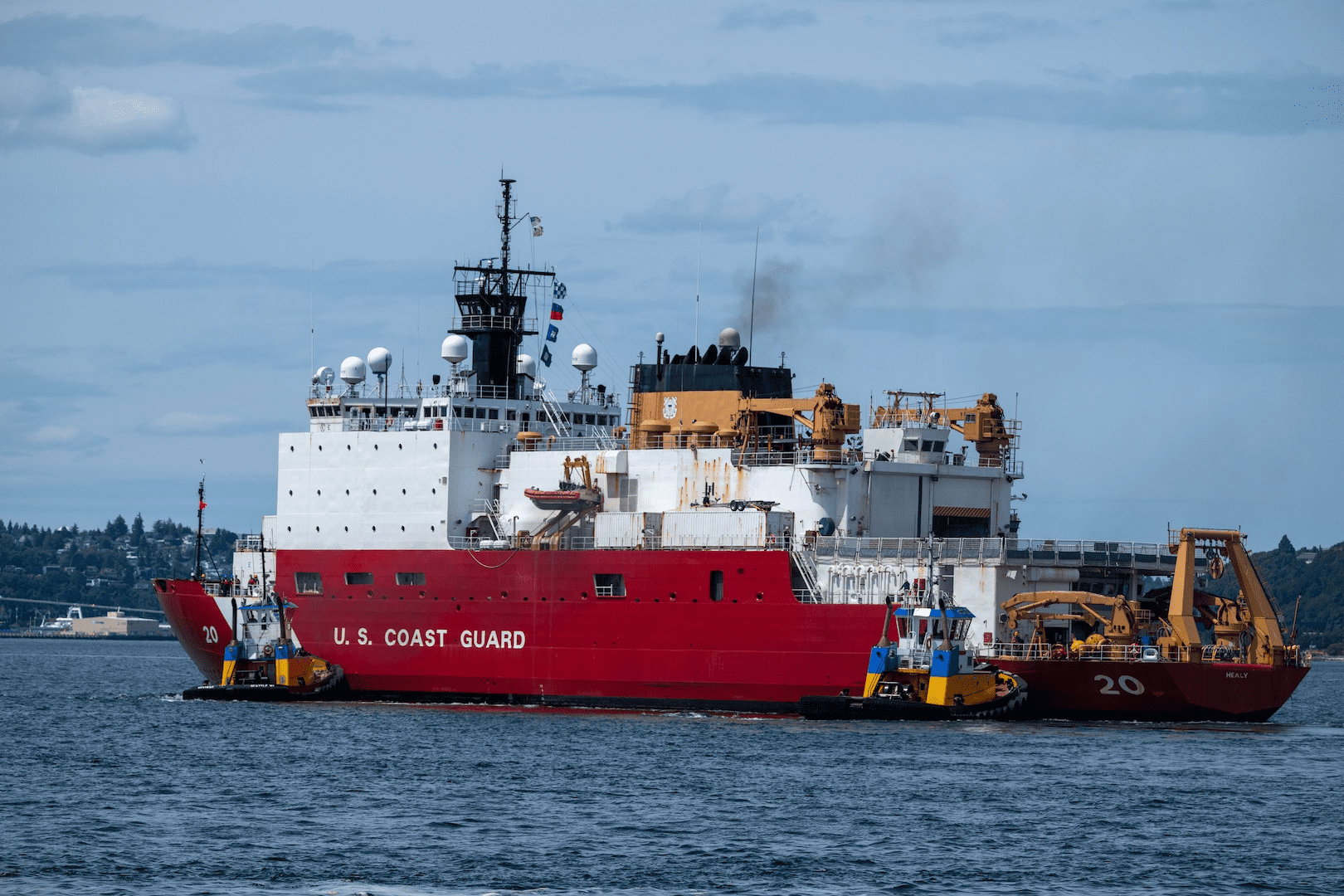

He is a Coast Guard veteran who served aboard the USCGC Polar Sea and USCGC Mallow as a navigator (Quartermaster). He has worked as an Able Bodied Seaman (AB) and a licensed mate and master. For the last 5 years he has sailed for the Masters Mates and Pilots union. He received his BA from the University of Washington in communications and was one of the first hawsepipers in Seattle to complete the upgrade to 3rd mate unlimited under the “new rules” of STCW ’95. He is a Coast Guard certified and experienced instructor for maritime schools in the Puget Sound area.

www.thenewhawsepipe.com

Join The Club

Join The Club

Leonard Lambert is the author of

Leonard Lambert is the author of