By Brian Platt

Aug 7, 2025 (Bloomberg) –The Canadian government is looking hard at developing a remote northern port on Hudson Bay as a conduit for exporting natural gas, potash, canola and other commodities as the country tries to reduce its economic dependence on the US.

Energy Minister Tim Hodgson said he sees “tremendous potential” for turning the port of Churchill, Manitoba, into a much larger export hub, opening new trade routes to Europe and other markets. The minister said he has seen multiple pitches for projects to move goods through the location, which is at almost the same latitude as Oslo, Norway.

“I believe there is an opportunity to make Churchill a far more strategic port,” Hodgson said in an interview with Bloomberg News. “If you look at what the Russians are doing, they ship for most of the year from their Arctic ports.”

The idea of a northern port enjoys the enthusiastic backing of politicians from Canada’s resource-rich western region, including Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe, whose provinces are major exporters of oil, gas and agricultural commodities.

Some observers are skeptical about Churchill as a viable shipping route. Turning it into a port capable of handling a wide variety of bulk goods would take years and cost billions of dollars, for a route that’s locked by ice much of the year.

But Hodgson is bullish on it. The government is in the midst of procuring a new fleet of icebreakers for the Canadian Coast Guard. With those ships, “you’re not talking about a four-month shipping season,” he said. “You could have a lane open for probably most of the year.”

Churchill’s port was first used as an outlet for grain exports in the early 1930s, and is the continent’s only deepwater port with direct access to both the Arctic Ocean and a rail line connecting south. The port has always been constrained by winter ice, and grain shipments through it plummeted when the Canadian Wheat Board lost its sales monopoly in 2012.

For products from western Canada, Hudson Bay is the closest route to Europe, Hodgson said. “It provides an alternative for all of the potash, canola, grain. If you have roads and you have more port facilities and more usage, more investment in the rail, all of a sudden Churchill starts to become pretty viable.”

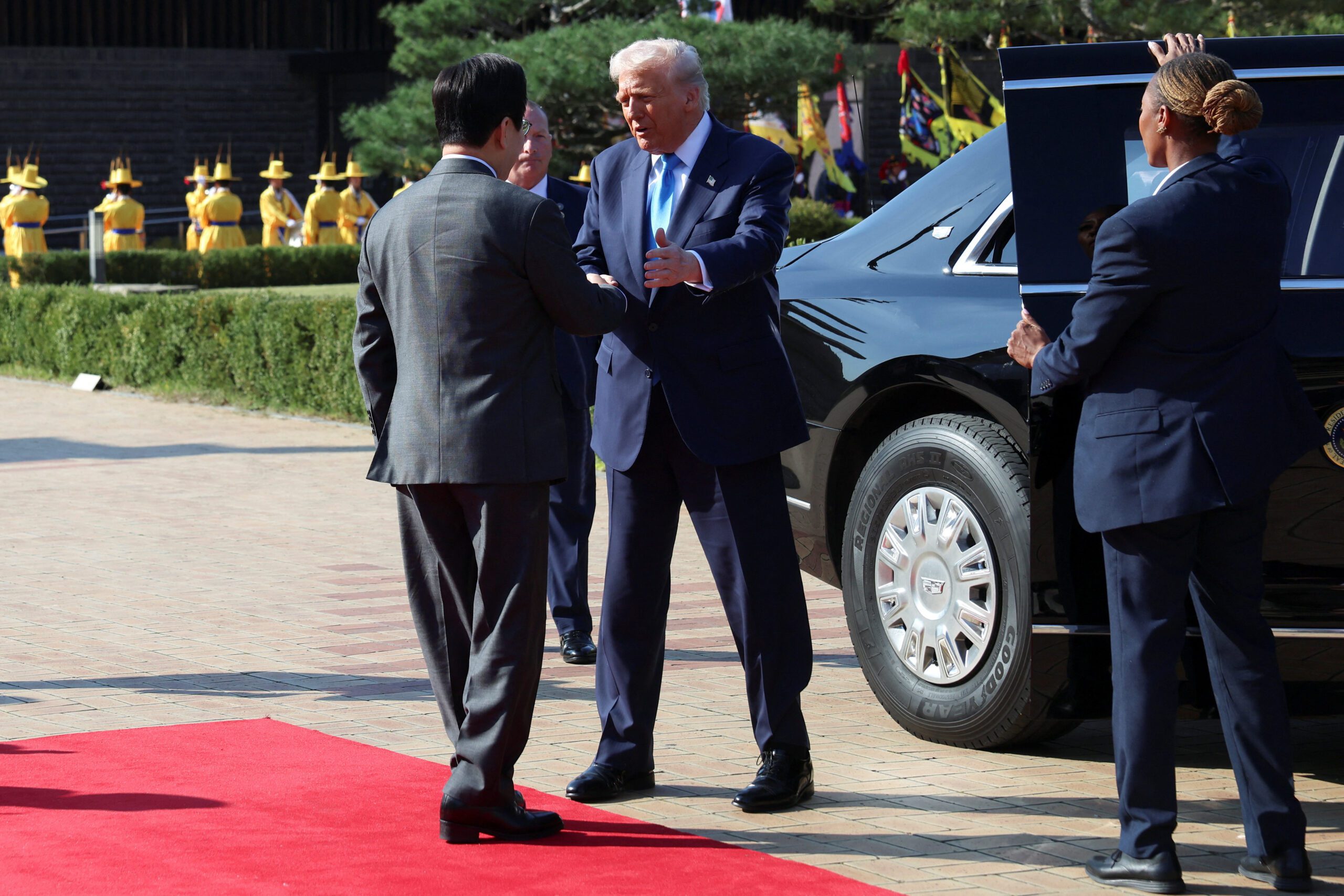

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government is preparing to accelerate approval of major infrastructure projects, largely as a response to the trade war started by US President Donald Trump. About three-quarters of Canada’s goods exports went to the US last year, and one of Carney’s top priorities is to bring that percentage down.

The government passed legislation in June to designate specific projects as being in the national interest, with the goal of approving them within two years. The projects will be prioritized based on criteria including whether they boost Canada’s economic security and advance the interests of Indigenous communities.

It’s the job of Hodgson, a former banker who worked with Carney at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and the Bank of Canada, to help turn those proposals into real deals.

“I have seen one where there’s a proponent on natural gas that would build an all-weather road beside the pipeline,” Hodgson said. He emphasized the effect this could have on the Indigenous communities in northern Manitoba, many of which are accessible only by plane.

“If you have an all-weather road up from southern Manitoba to Churchill, you fundamentally change the economics of all the critical minerals throughout,” he said. “You also fundamentally change the cost of living of every community right along the line.”

He pointed to the support of Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew, who is himself Indigenous, as especially crucial for getting projects built to Churchill.

“I have seen a level of coordination between the provincial government in Manitoba, the First Nations and Metis peoples in Manitoba and certain proponents that looks very promising. Probably more so than any other,” he said.

Some are highly doubtful the economics will ever make sense for Churchill.

“Are we forgetting that we’ve been trying this for a hundred years?” said Heather Exner-Pirot, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute who specializes in northern and Indigenous resource development.

She said proposals for Churchill are almost always generated from governments or First Nations groups, and she’s skeptical there are private sector shippers serious about using the port. Insurers are unlikely to sign off on an extended shipping season any time soon, and year-round ice-breaking would probably run into trouble with Inuit land titles and environmental considerations, she said.

“I just can’t believe that it’s easier to do it through the Arctic in the winter than to go over land,” Exner-Pirot said, arguing the return on investment would be much higher going to the west coast or using existing east coast ports.

Still, there are new considerations at play as Carney’s government searches for fresh trade routes.

Churchill has seen a modest revival in the past decade. In 2018, the port and the connecting rail line were purchased by Arctic Gateway Group, which is owned by a partnership of 41 Indigenous groups and communities in the region. The rail line now has four weekly trips — two freight trains and two passenger trains — and the port has expanded its storage facilities for critical minerals.

With Trump’s tariff agenda, “what we offer becomes so much more important to help us with our national agenda, which is to diversify our trade away from the US and help us become a global energy superpower,” said Chris Avery, chief executive officer of the Arctic Gateway Group.

Avery said the port aims to ship 20,000 tons of zinc concentrate this year, and he expects some grain shipments before the ice returns. Ships taking supplies to the far north also use the facility.

Avery said he hasn’t yet met with Hodgson, but agrees that year-round shipping from the port is feasible with icebreakers. The current shipping season is about four months, but he’s working with University of Manitoba researchers to try to convince insurers that it’s closer to six months now.

Asked whether oil exports could ever be an option through the port, Avery said he’ll always listen to proposals from the private sector, but added that “nothing has come forward specifically around that.”

There are other proposals for shipping through Hudson Bay, including one group pitching a liquefied natural gas export facility further south on the coast. Avery said he could only speak to the opportunity represented by the existing assets in Churchill.

“The rail line is in better condition than it has been for the past 30 years,” he said, noting the company is also modernizing the basic port facilities, such as the wharf decks.

“This whole set of infrastructure is ready to serve the country,” he said. “We just really fully need to leverage it.”

© 2025 Bloomberg L.P.

Join The Club

Join The Club