, click for larger

(Bloomberg) — Mario Monti’s government is trying to attract as much as $18 billion in investment to Italy by relaxing a ban on offshore oil and natural-gas exploration imposed by Silvio Berlusconi after the 2010 Gulf of Mexico spill.

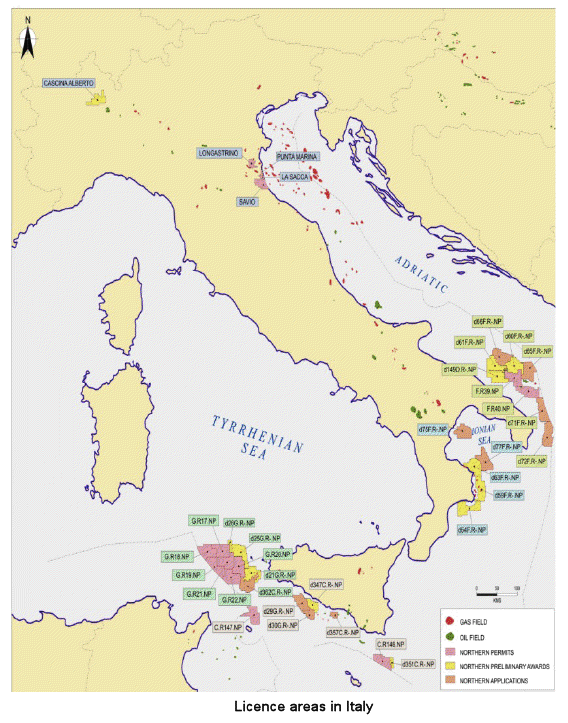

The premier, who must jump-start the economy to help stem Italy’s debt crisis, last month ruled that companies such as Eni SpA, Edison SpA and Royal Dutch Shell Plc can resume shallow- water projects within 12 kilometers (7 miles) of the coast they were forced to abandon in 2010. The decree needs Parliamentary approval and the lower house is set to debate it July 23.

Monti is brushing aside opposition from environmental lobbyists to get more crude and gas flowing to the energy-poor nation while helping Shell, Europe’s largest oil company, pay off its investment. Offshore output could double within a few years, attracting 15 billion euros ($18 billion) in spending, Economic Development Minister Corrado Passera said. It also may reduce Italy’s energy bill by 6 billion euros, he said.

“The Italian government is strongly committed to resume the domestic oil and gas production,” said Nicolo Sartori, an energy and defense analyst at Rome’s Institute for International Affairs. “The resumption of exploration activities won’t represent a game changer, but it will ease a situation of high dependence on imports and high prices.”

Spokesmen for Eni, Italy’s largest oil company, and Edison SpA declined to comment before the legislation is decided. A Shell spokesman wasn’t immediately available.

Italy imports about 90 percent of its domestic oil and gas demand and is fighting to regain investor confidence as the financial crisis threatens to cut off market funding to the euro area’s third-biggest economy.

Sicily Insolvent?

Monti yesterday had a meeting with Italian President Giorgio Napolitano to discuss Sicily’s financial position after expressing concern that the region might be insolvent.

Italian consumers burned 71.3 billion cubic meters of gas in 2011, ranking ahead of all European nations by that measure except for the U.K. and Germany, according to a BP Plc survey.

The decree would allow existing offshore projects to start again, without allowing new ones. It’s enmeshed in the Monti government’s broader legislation to spark economic growth, making it more difficult to be shot down by the chamber of deputies next week or later in the Senate, which must approve the decree by Aug. 25 or it will expire.

“It’s perfectly achievable,” said Brian O’Cathain, Chief Executive Officer of Petroceltic International Plc, which drills for hydrocarbons in Italy. “There’s an enormous gas and oil potential in Italy, and the current government is quite keen on developing its indigenous resources.”

Oil Output

The Mediterranean country’s 2010 oil output reached 5.7 million metric tons, the third-largest among European Union nations after the U.K. and Denmark, according to the International Energy Agency.

The ban was imposed by ex-Prime Minister Berlusconi’s center-right coalition in the summer of 2010. Removing some of its restrictions could bring in as many as 25,000 jobs to the country with a 10.1 percent unemployment rate, Passera has said.

The decree has been criticized by analysts for not going far enough in attracting investors because it doesn’t fix Italy’s complicated and sometimes arbitrary regulatory environment. It can take several years to get approval from local authorities before exploration can resume, said Roberto Ranieri, energy analyst at Caboto Sim SpA in Milan.

Environmental Opposition

The government is up against Italy’s environmental groups including Legambiente, which claims that the country’s offshore oil and gas supplies are too small to exploit and risk a disaster like when the Macondo well exploded in the Gulf, causing the largest U.S. offshore oil spill.

“The government is just doing a favor to individual oil companies,” Stefano Ciafani, Legambiente’s vice chairman, said in a phone interview. “The country doesn’t need it.”

Italy’s reaction to the spill at BP Macondo well was “totally disproportionate,” Petroceltic’s O’Cathain said. “Up until June 2010 the Italian state was encouraging direct foreign investment in oil and gas. It wasn’t reasonable to suddenly cancel all the ongoing projects and have those investors incur serious losses.”

– Ladka Bauerova and Chiara Vasarri, Copyright 2012 Bloomberg

Join The Club

Join The Club