Diving deep below the ocean, saturation divers occupy a world few can imagine. Named for the physiological phenomenon where their bodies become “saturated” with dissolved nitrogen from prolonged dives, these professionals defy the usual constraints of the diving world.

While recreational divers may venture 30+ feet underwater and employ a method of slow ascent to prevent decompression sickness, the world of saturation diving is a different ball game. These professionals often work at staggering depths, sometimes reaching up to 1,000 feet. To safely decompress from such depths using traditional techniques would take days. Instead, saturation divers are transported to the ocean’s surface in pressurized diving bells. From there, they’re moved to specialized chambers for decompression. These chambers, where divers might rest on cots, catch a movie, or receive meals through pressurized compartments, become their temporary residence.

Economically, it wouldn’t make sense for companies to pay these divers for short bursts of work, followed by prolonged rest periods. Herein lies the extraordinary part of their job: they remain under pressure. Once a diver’s body reaches the saturation point, no additional nitrogen can be absorbed, regardless of the duration underwater. So, instead of multiple decompressions after each dive, they maintain the pressure—sometimes for up to 28 days.

This duration spent in hyperbaric chambers, mimicking the pressure of deep waters, is known as “the storage depth.” It’s only at the job’s end that they undergo the slow and crucial decompression process, eventually emerging to breathe freely in the open air. For every 100 feet they venture below, a saturation diver will spend about a day decompressing in this chamber.

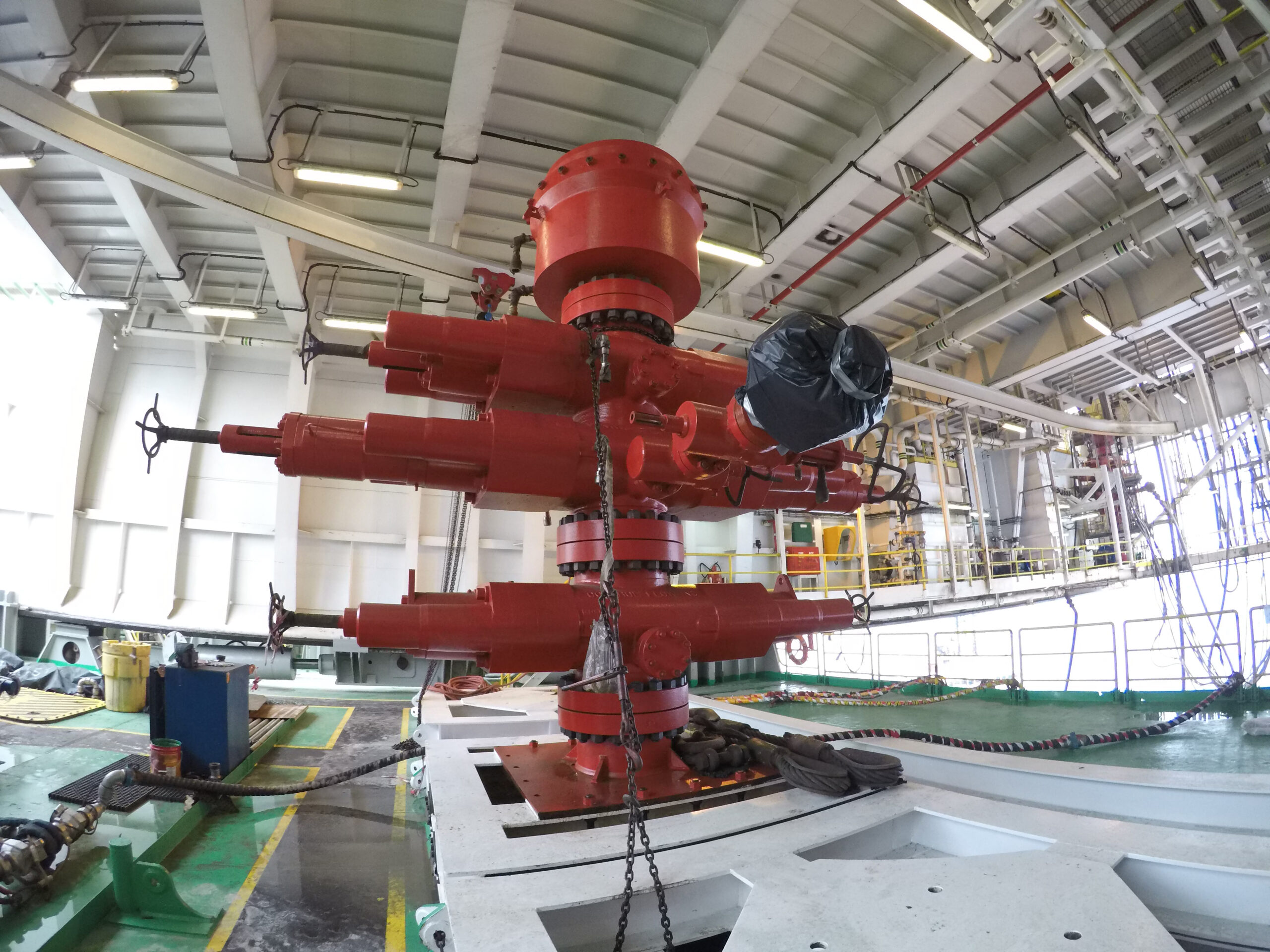

Saturation divers play an indispensable role in the offshore oil and gas industry, venturing deep into the ocean to ensure the structural integrity and functionality of underwater infrastructure. These divers perform a range of tasks from inspecting pipelines, rigs, and platforms, to conducting repairs, maintenance, and installation of equipment. Given the challenging and high-pressure environment, their expertise is crucial in safeguarding the smooth operation of offshore drilling and production activities. Their work not only bolsters the efficiency and safety of the industry’s underwater assets but also aids in preventing environmental hazards that could arise from equipment malfunctions.

Saturation diving is one of the most unique—and dangerous—offshore occupations.

Let’s dive in.

A Glimpse into History: The Birth of Saturation Diving

When a diver is underwater, the pressure increases by one atmosphere for every 33 feet of depth. Under this increased pressure, breathing compressed air means that more nitrogen is dissolved into the diver’s blood and tissues than at surface pressure. If the diver ascends to the surface too rapidly, the dissolved nitrogen forms tiny bubbles in the tissues of the body.

This phenomenon causes decompression sickness, commonly referred to as “the bends.” Decompression sickness can lead to joint and limb pain, numbness, dizziness, breathing difficulties, skin rashes, and even paralysis or unconsciousness. In severe cases, decompression sickness can lead to shock or death.

The concept of saturation diving emerged in the mid-20th century as a solution to the decompression risks posed by traditional deep-sea diving. In the 1960s, a breakthrough came with the realization that once tissues are saturated with inert gas (like nitrogen) at pressure, no further gas is absorbed, and the decompression time won’t increase regardless of the time spent underwater.

So, the concept of saturation diving was born. Divers could live in specially designed pressurized chambers for weeks, transported to work sites in pressurized diving bells. When their shift ended, they underwent one long, controlled decompression.

The offshore oil and gas industry was a significant benefactor. Saturation diving allowed longer work times at deep underwater sites, making it feasible to construct and repair the deep-sea infrastructure necessary for oil and gas extraction.

What Is It Like to Live Under Pressure?

Given its unique nature, many aspects of saturation diving are both intriguing and out of the ordinary:

Breathing Mixed Gases: Instead of breathing regular air, saturation divers often breathe a mixture of oxygen and helium, known as heliox. This mixture reduces the narcotic effects of nitrogen at depth. One amusing side effect is that helium can make the divers’ voices sound high-pitched, like a cartoon character.

Hot Water Suits: The deep-sea environment is incredibly cold. To counter this, saturation divers often wear hot water suits. These suits have water channels through which warm water circulates, keeping the diver warm during their work.

Hyperbaric Life Support: Living under pressure means all life necessities—like food, water, and waste management—need special considerations. For instance, food is sent into the chamber through an airlock system, and it needs to be packaged in a way that won’t be affected by the pressure.

Extended Isolation: Being in a small, pressurized chamber for weeks at a time can be mentally challenging. Divers are isolated from the outside world, with limited means of communication and entertainment. Maintaining good relationships with fellow divers is crucial in such close quarters.

Unique Health Monitoring: The human body reacts differently under prolonged pressure. Divers must be closely monitored for any signs of High-Pressure Nervous Syndrome (HPNS), decompression sickness, or oxygen toxicity. This constant health surveillance is crucial for the divers’ safety.

Depth and Time Limitations: The deeper the dive, the more helium the divers breathe, but there’s a limit to how deep humans can safely go, even with mixed gases. Current saturation diving operations may be conducted at depths of about 600 feet, although most are much shallower.

Saturation diving is a testament to human adaptability and the lengths we go to in pushing our boundaries.

The Risks of Saturation Diving

Living in a pressurized environment and working hundreds of feet underwater is just as dangerous as it sounds. There is no room for error; the following two incidents are proof of just that.

On November 5, 1983, a semi-submersible drilling rig called the Byford Dolphin was drilling in the Frigg gas field in the North Sea. Four divers were in a compression chamber system on the rig, connected by a trunk (a short passage) to a diving bell. They were at a pressure of 9 atmospheres, equivalent to a depth of nearly 300 feet below sea level.

Two dive tenders were on the outside of the chamber, assisting the divers. When one of the tenders opened the clamp to disconnect the diving bell, there was an explosive decompression. The chamber’s internal pressure rapidly equaled the atmospheric pressure outside in a fraction of a second.

The explosive force of the decompression was devastating. All four divers inside the chamber and one of the tenders outside were killed almost instantly. The rapid depressurization resulted in violent and deadly physical effects on the bodies, marking it as one of the most horrifying accidents in offshore history. An investigation into the accident revealed that the clamp had been prematurely opened—before the pressure in the chamber had equalized to the pressure inside the diving bell.

The Byford Dolphin tragedy had profound implications for the offshore and diving sectors. It highlighted the critical importance of rigorous safety protocols and thorough checks during decompression. The incident also underscored the need for comprehensive training for diving personnel and sparked debates on equipment design, urging the industry to prevent similar incidents in the future.

Another North Sea saturation diving incident had a miraculous outcome, spurring the creation of Last Breath, a BBC documentary that has been featured on Netflix. In September 2012, saturation diver Chris Lemons found himself in a life-threatening situation when he was dispatched to make alterations to an oil well situated about 127 miles east of Aberdeen, Scotland.

While Lemons was working underwater, a storm above the surface wreaked havoc, overriding the GPS of the dive support vessel he was tethered to. The vessel drifted away, severing the umbilical cable that was supplying him with breathing gas. Left with a mere five-minute oxygen supply in his reserve tank, his survival seemed bleak, especially as the storm had thrown the ship off course.

It took the crew over 15 minutes to regain control, locate, and retrieve what they believed was Lemons’ lifeless body. Astonishingly, after 33 of the 38 minutes without oxygen, Lemons was resuscitated. His survival after such a prolonged period without oxygen remains a topic of discussion among experts and has transformed his story into a compelling testimony of human resilience.

The Future of Saturation Diving

With the risks to consider, plus advancements in automation and offshore equipment, one may wonder whether (or when) human divers will be largely replaced by machines.

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) and Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) have made vast inroads in tasks that traditionally required human divers, especially in sectors like offshore oil and gas. Using machines like ROVs offers clear benefits. For one, the safety concern is paramount; machines are immune to threats like decompression sickness or oxygen toxicity that human divers face. Additionally, these machines can operate for extended durations and reach depths that are far beyond the safety limits for humans. On top of this, the advanced capabilities of some ROVs allow them to carry out tasks with precision that might be challenging for humans, especially in demanding underwater conditions.

However, writing off saturation diving entirely in the face of these advancements might be premature. Human divers possess a unique versatility, adapting quickly to unexpected situations in ways that machines are still learning to emulate. Some tasks are so intricate that they benefit from the nuances of human intuition, decision-making, and adaptability.

It’s also worth noting that much of the existing underwater infrastructure, particularly older installations, was designed with human intervention in mind. Retrofitting or adapting these for ROV-based maintenance or operations might present challenges that outweigh the benefits. We also can’t ignore that current technology has its limitations. There are specific underwater environments, especially those characterized by high turbulence, silt, or other challenges, where human divers might still hold an edge over machines.

As the landscape of saturation diving continues to evolve, offshore operators must put safety first to minimize the risks that divers and their support teams face. From training to equipment maintenance to storm surveillance, every aspect of diving operations must be handled with the utmost care.

###

Arnold & Itkin is known nationwide as a leader in maritime law. The firm has represented offshore workers and their families after the worst disasters, such as the Deepwater Horizon explosion and the loss of the El Faro. The firm’s trial attorneys have fought for life-changing results on behalf of clients in all walks of life, securing more than $15 billion in verdicts and settlements. When maritime workers’ lives are put on the line because the companies they work for emphasize profits and production over safety, Arnold & Itkin works tirelessly to see justice served. No matter what.

Unlock Exclusive Insights Today!

Join the gCaptain Club for curated content, insider opinions, and vibrant community discussions.

Join The Club

Join The Club