Was The World’s ‘Northern-Most Island’ Erased From Charts?

by Kevin Hamilton (University of Hawaii) In 2021, an expedition off the icy northern Greenland coast spotted what appeared to be a previously uncharted island. It was small and gravelly,...

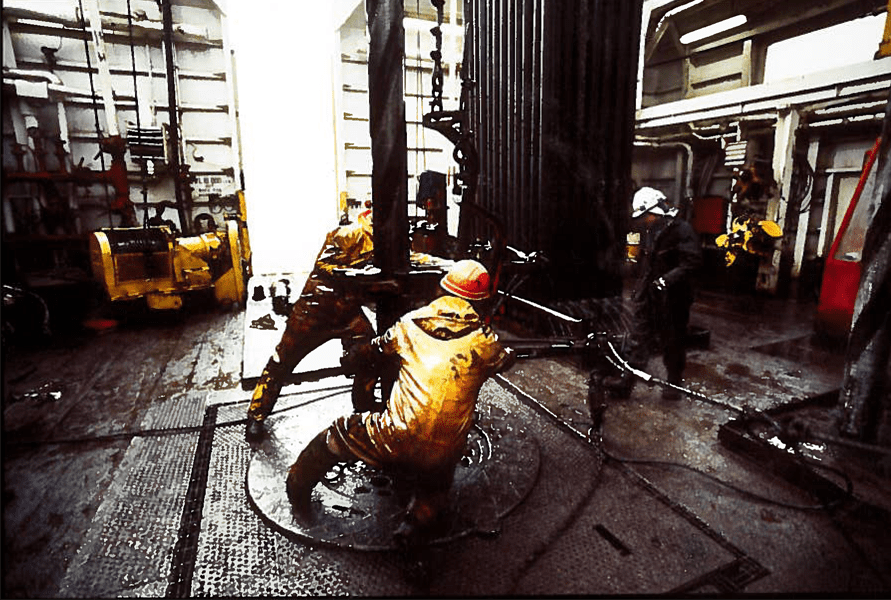

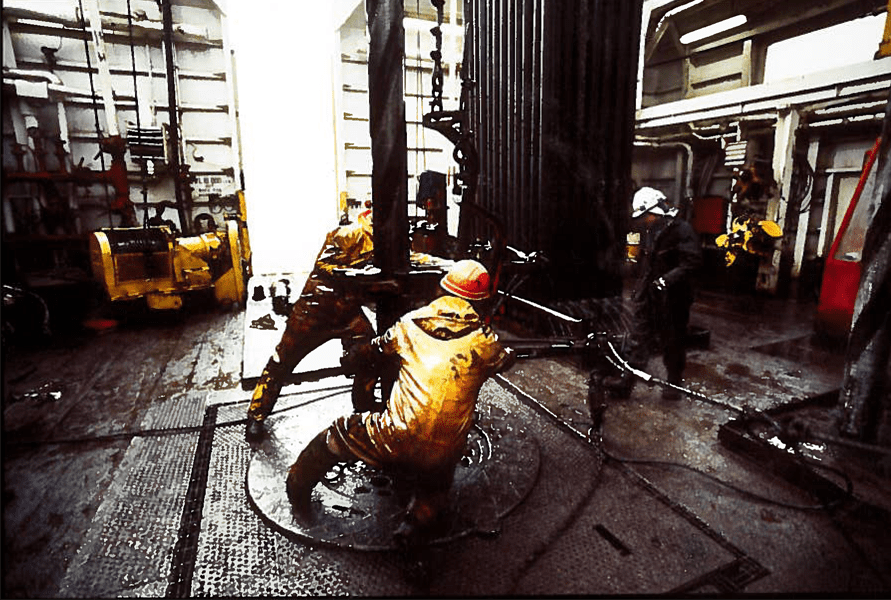

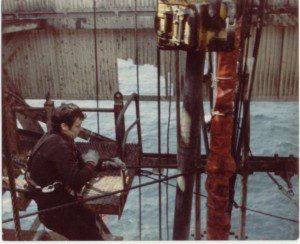

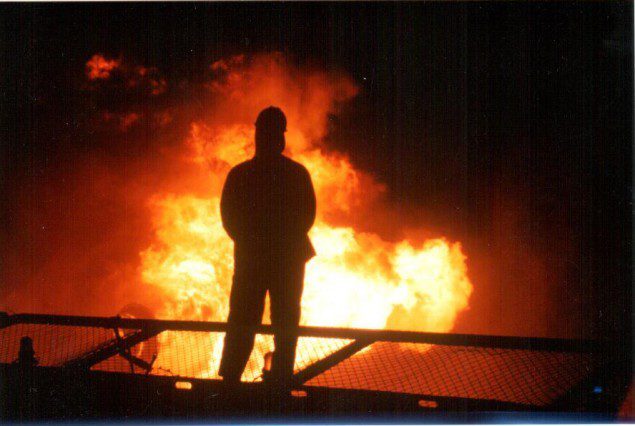

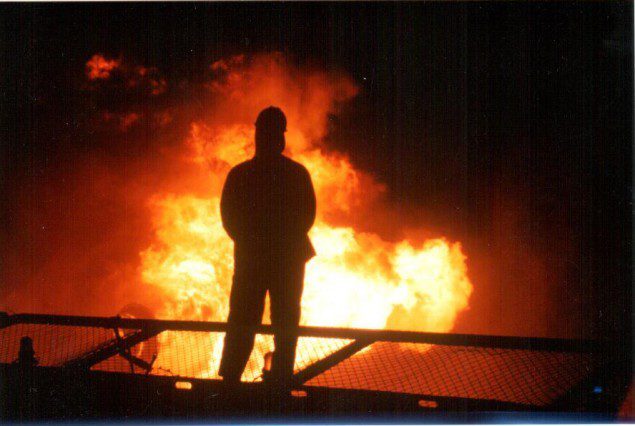

Breaking out the BHA, image: Stena Drilling

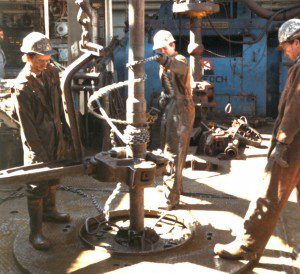

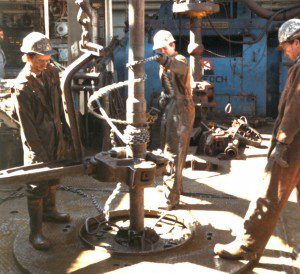

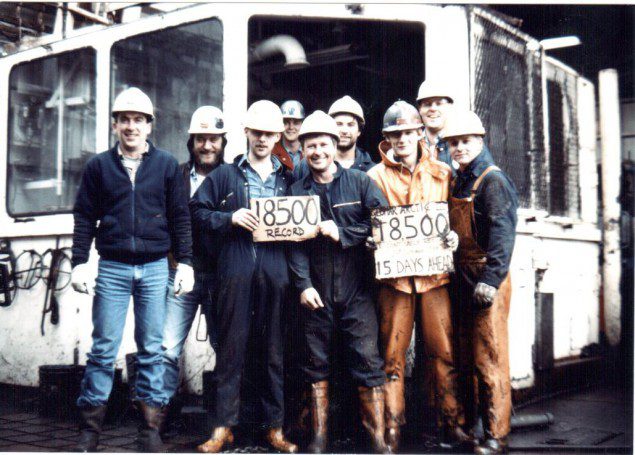

In the days when physical manual work was an every day occurrence

– by George Cheyne, Senior Toolpusher, Stena Carron

It was a crisp December morning back in 1978 that I boarded my ï¬rst-ever plane to take me to Norway where I was to join my ï¬rst drilling rig, at 21½ years old this was my ï¬rst time away from home, other than the annual seaside trips to the Broch as a youngster. I had signed up with an agency in a desperate effort to join those working on the rigs, seeing my mates with their sports cars and beautiful seat covers made me jealous. The call came through one afternoon from a polite lady at the agency asking if I would stand in for a person who was sick, and would be required to spend Christmas and New Year offshore.

I jumped at the chance and duly accepted her offer. I had to be at Dyce airport the following day at the ungodly hour of 6am, half way through the night for a 21 year old. I was told that my coveralls, boots and hard hat would be waiting for me at the airport. At the time I held neither an offshore medical nor a survival certiï¬cate, or RGIT as it was commonly known. The promised attire had never turned up at the airport, how could that polite lady from the agency have forgotten?

Arrival at the rig was by launch boat. The rig had just arrived at a fjord close to Bergen after some heavy weather damage. Armed with my kit bag, I had to jump off the boat onto the rig’s pontoon and make my way up the column ladder to the top deck and followed the rest of the men into the accommodation. I was led into an ofï¬ ce resembling a make shift hospital, no welcome onboard, no induction. The only thing passed to me was a small ticket from the Medic showing me where my lifeboat was.

The Medic was a person that everyone knew and he apparently seemed to be in charge in a sort of way that Medics do. Oh yes, the Medic was the lawmaker alright, he controlled the movie inventory, the bond, bunk allocations and would report to the Superintendent or Offshore Installation Manager as some were called. Those who spent their life in the drilling side preferred being addressed as the Rig Superintendent, others apparently who spent their lives at sea were given the posher accolade of OIM and had little time for drilling sorts who were always covered in mud, swore profusely and generally broke a lot of stuff.

The Medic then ushered me through to another ofï¬ce. Above the door a sign read ‘Rig Superintendent’. Nerves started to build up as I’d heard about these Superintendents at home in the pubs, they were classed as a higher authority than God and possessed unmatched skills in reducing other humans to quivering wrecks. As I was shown in, the Medic said some words to the Superintendent who was sitting at his desk with his feet up reading the latest Mississippi Times, an abrupt being who offered little in the way of small talk said in a deep southern American drawl “git yer coveralls on an git to work.” No eye contact was offered and no other words were exchanged.

Coveralls?

I had none. What was I to do, I couldn’t tell the Superintendent for fear of being executed on the spot. So I did the only thing I could do and that was to report back to the Medic and seek solace. He might feel sorry for me and get me sorted out. How wrong I was, after several expletives complaining about agency hands never having their own gear I was marched through to the engine room ofï¬ce to meet the Chief Engineer who I was to be reporting to as Motorman for the next two weeks.

Now, the Chief Engineer while also blessed with an abrupt and condescending manner was a learned gent who had spent all his years at sea on boats prior to joining the drilling rigs. If, during onversations with the man, the word boat ever slipped out one would get a scowl from over his spectacles and a stern reminder that he worked on ships – boats were for ï¬shermen.

His grumpy attitude gave me the impression that he was jealous that an unqualiï¬ed individual such as the Rig Superintendent was able to command the rig with such respect and that as a Chief Engineer he was only called to task when things broke. The Chief Engineer was always complaining about his workload or making derogatory remarks about the drill floor, or of not having enough hours in a day to get his work done. I don’t know what kind of clock the Chief used but everyone else had 12 hours in their day. Moans about being under paid were more often than not brought up during conversations with the Chief Engineer, of course times have moved on and these utterances are rarely heard today…

Next in line to the engineering throne was the Second Engineer, usually an individual who would go to great lengths to throw a spanner in the works to show the Chief in a bad light. The Second Engineer, unlike the Chief, was more human like, approachable and spent an inordinate amount of time in the coffee shop. Obviously his clock worked ï¬ne since he could perform all of his duties before the ï¬rst smoko which afforded him time to read the endless supply of newspapers that came his way. He worked night shift and loved it, always managed to stay clean and avoided any journeys to the drill floor, as fraternizing with drillers would not be good for his image.

Reporting to the Second Engineer was the Motorman. This was to be my job, engine room duties and stress doll stand-in for the Chief Engineer. It was to be a short tenure in the engineering department.

It’s not that I wanted to work on the drill floor, I was encouraged to do so by the engineers that I idolized. I had been on the drill floor several times fixing tuggers and oil checks but all those wires n stuff hanging from the sky and the screaming from a small white house in the corner by an angry individual they called the Driller didn’t appeal to me. A few more trips passed and my peers continued to encourage me to take up employment on the drill floor. More money could be made, of course you would lose a finger or two along the way but what the hell there was five on each hand. Rapid promotion was always available to anyone who dared take up the challenge as at least one or two souls would get ‘run off’ each trip. The term ‘run off’ meant just that – you could be run off the rig for no apparent reason. If the driller didn’t like your face, you spoke out of turn or taking a minute too long for meal breaks were all legitimate reasons to get yourself run off.

However after about 9 months in the engine room I took up the challenge of working in the drilling department, after all I had been encouraged to go there for some reason, perhaps the engineering group just wanted rid of me, I’ll never know. A slot came up when one of the Roughnecks decided to call it a day and I was promptly sent for. The only floor experience I had was watching the drill crew ‘tripping pipe’ the night before. A fantastic sight, a bit like the formula one teams in the pit lane, every person had a job that was timed to perfection. The Driller was in charge and he was blessed with the amazing ability to shout as loud as he could all shift, while tripping pipe his vocabulary was limited to ‘slips!’ and ‘make em bite!’ as loud as he could. Hmmm one day I may be able to do that…

Next morning the big day had arrived. I had been promoted to Roughneck without having touched a set of tongs or had the slightest incline of what was going on (no change there….). I was escorted up to the floor by the other Roughnecks and told we were fishing and that it would be a wet trip. I looked up at the sky but could see no evidence of rain nor any signs of fishing tackle but then again these guys were seasoned Roughnecks and I knew that they would be winding me up since I was the green hand on the crew. I stood and watched the off-going crew trip a few stands and was promptly given a set of tongs to hold while one of the guys instructed me in how to ‘make em bite’. As every Roughneck will testify, handling rig tongs for the first time must be quite comical for the onlooker. As I tried to make them fit around the pipe and make them bite at the correct time I ended up on my backside with a set of tongs swinging above my head out of control, all I could hear was the growl from the Driller behind me calling me a ‘worm’. That’s what we got called if we didn’t perform. At times we were all worms together, sometimes just one of us could be the worm and sometimes we called each other worms. Of course we Roughnecks had an equally slanderous name for our Drillers but Ed won’t let me print it. The Driller was God on the drill floor, anything he commanded us to do we had to do, there were never any niceties nor small talk with the Driller. We tried to stay out of his sight most times but he always wanted to know whatwe were doing, which was strange because in between scrubbing the rig floor we would be scrubbing and after that was finished we would get more scrubbing to do.

As we tripped pipe out of the hole I was given lessons on what was going on. As we fished for whatever we were fishing for (not real fishing but fishing down the well for some form of debris) and tricks passed on by my peers on how to make handling rig tongs and slips look like a piece of cake. Smoko (coffee break) came. I was privileged to be the first to go and had to hurry back as the others had to have their break and be back in time for the Bottom Hole Assembly (BHA). No sooner had I arrived in the tea shack than I was being called back by the Driller. This was normal, we were given few breaks and when we did they were more often than not cut short. I ran back up the stairs two steps at a time still eating my hard earned tabnab (small fancy piece or sandwich). As we worked our way closer to the BHA I was starting to get very hungry and looking forward to lunch, which I hoped would at least give me time to digest and enjoy. This was not to be since the BHA was nearing surface none of us was allowed to leave. The Assistant Drilller, who was ‘the Drillers Spy’, appeared with three silver trays of food and one by one we could step behind the drawworks and eat on the run.

As my first shift drew to an end I was feeling tired and weary, wet and cold and longing for a nice long hot shower and bed as I was absolutely wiped out. The showers were a communal affair (where was the soap holder, best not to know the answer that was given) and the toilet cubicle doors had long since broken off. The rooms were four man cabins with two from each shift sleeping in them at the same time in bunks that had no curtains, there was no panelling or décor in the cabins, but at least you could hear the mud pumps running. Oh how I wanted to go home.

After shift and showered up we would all meet in the rec room. Movies would be selected and one person would be in charge of the projector. DVDs had not been invented, nor was TV available offshore. Computers were a thing only NASA used and mobile phones were a fantasy dream of the future. A standard length movie would be three reels long and a blockbuster would stretch to four. The first reel would be loaded and the movie played to the whole crew, who despite a hard days work always found the time to socialise after work. This created a different kind of atmosphere than the one on shift as even the Driller and his assistant would crack a joke or two and even force a smile (they were real people after all). The first part of the film over and the reel had to be rewound and put back in the box before the next reel was loaded; this afforded everyone a chance to get some ice cream, tea etc and generally prompted some sort of banter amongst the crew. There was a strong camaraderie back then, we worked hard, were treated mean and socialised hard on and off the rig. There was a lot of fun in between but when we worked it was often extremely miserable, only made bearable by the leave period and the wages.

There were many incidents, a lot of them never taken too seriously. A broken finger did not guarantee you a chopper home. A broken finger would get a splint and a headache pill from the Medic. He would decide if you were fit for work or be placed on light duties. There were no investigations conducted, no reporting card system, no stop the job authority and the crew safety meetings were ‘steered’ by the Toolpusher. Each crew had their own safety record and competition between crews was fierce. Some crews had years of LTA free days where others had only days. If you were unfortunate enough to be on a crew with a high number of days then you’d better not have an accident for fear of losing your place, or your job.

Now, the Toolpusher was an individual who had served his time as a Driller, had drilled holes in the ground all over the world, could tell the Driller what to do and take no prisoners in doing so. There was nothing we had done that he hadn’t and he displayed an air of God-like authority. His gloves were always new, unlike ours which had to be reused and had to last for two weeks, one pack of 10 pairs for 14 days didn’t work out for some reason. The Toolpusher made our Driller, who spat and growled at us at every opportunity, look like Peter Pan. The Toolpusher was one to be avoided at all costs. To get caught out by the Toolpusher was not good, you had to perform to perfection in every way in his presence. Making eye contact with him was not recommended. Of course there were those whose attitudes changed when the Toolpusher appeared, suddenly they became energetic, knowledgeable and started using their initiative when he was around working very hard to impress him and perhaps befriend him. You could spot them a mile off and a soon as the Toolpusher was out of sight would revert back to their previous state of getting away with what they could.

As I eventually mastered roughnecking on the drill floor I started to get familiar with other aspects of drilling like being on shaker watch. Watching cuttings and drilling mud pour over the shakers for hours on end, how interesting. The shaker room, or shakers, as it was called wasn’t really a room. Three vibrating shakers making a lot of noise and a grating floor which allowed you to look directly into the sea below afforded no comforts whatsoever during the colder days. It would be many years before a heater for a Roughnecks comfort reached the North Sea. The only respite was the call from the Driller over the phone ‘connection’, abruptly said; I had to leg it up the stairs to assist the other Roughnecks make a drilling connection. In those days running down or up a stairs was encouraged as sauntering along was considered to be time wasting, handrails were used to get down the stairs quickly.

The most respite a Roughneck could get in wooden derrick days was when down-hole logging was going on. Sometimes this would last for weeks and afforded us time to paint and do maintenance at a more leisurely pace. Even our breaks were more relaxed and sometimes we got 20 minute meal times. But the Toolpusher or the Driller was ever watchful and made a point of looking at their watches as a gesture that perhaps we should return to work. Of course if we ignored this body language then that was it, an opportunity for him to get angry. ‘Ya all needs to git ya ass to the floor’ he blurted. I looked around for the rest of the ‘ya all’ but there was only me and the strange thing was when a group of people were being addressed it was ‘All ya all’. I couldn’t figure this one out despite having gone to school.

Republished with permission from Stena Drilling Flowline Magazine

Join the gCaptain Club for curated content, insider opinions, and vibrant community discussions.

Join the 105,924 members that receive our newsletter.

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Access exclusive insights, engage in vibrant discussions, and gain perspectives from our CEO.

Sign Up

Maritime and offshore news trusted by our 105,924 members delivered daily straight to your inbox.

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up