(1837-1861), Lithograph by N. Currier, U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph

– By Alasdair Roberts

(Bloomberg) — In the early years of the American republic, Sackets Harbor in upstate New York was one of the U.S. Navy’s most important ports, guarding access to the St. Lawrence River. In the War of 1812, Americans repulsed two British assaults there. As the war ended, they erected an odd memorial to their victories: the forlorn, uncompleted hulk of the battleship New Orleans.

It could still be seen rotting on its stocks 70 years later. If it had been launched, the New Orleans would have been one of the most powerful ships in the Navy. It was larger than Horatio Nelson’s HMS Victory. But when peace came, construction stopped and the New Orleans began its long decline.

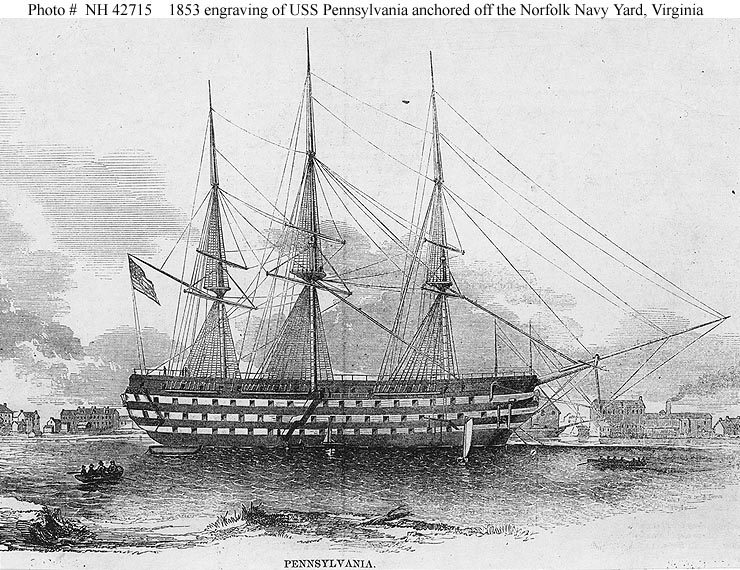

It wasn’t alone. From 1813 to 1816, Congress authorized the construction of 16 large battleships. In 1830, only one was on duty. Six were launched but quickly removed from service. Six others stood incomplete in naval yards. Frederick de Roos, a British officer visiting New York in 1826, was startled by the condition of the USS Ohio, put into storage immediately after launching in 1820. “A more splendid ship I never beheld,” he wrote. “She is already falling rapidly into decay.” In Philadelphia, de Roos marveled at the USS Pennsylvania, designed to be the largest fighting ship of any nation, whose hull had never touched water.

This was the ghost fleet. It was a product of the nation’s struggle, in the first decades of the 19th century, to reconcile its mercantile ambitions with its deep ambivalence about the expansion of a national-defense establishment.

Production of Empire

Americans were a trading people “traversing all the seas,” as Thomas Jefferson said, “with the rich production of their empire.” By 1830, the U.S. had the second-largest merchant fleet in the world. But the expansion of trade wasn’t easy without naval protection. This had been the lesson of the War of 1812, which was triggered by American frustration about British interference with its merchant fleet. It was a war for “free trade and sailors’ rights,” President Theodore Roosevelt later wrote. “Meaning by the former expression, freedom to trade wherever we chose without hindrance save from the power with whom we are trading.”

The naval buildup of 1813-1820 was supposed to provide the merchant fleet with the protection it badly needed. But enthusiasm for the expansion was short-lived. Instead, the government became obsessed with fiscal retrenchment. Andrew Jackson, elected to the presidency in 1828, said his aim was to eliminate the national debt entirely within his administration. Extinguishing the debt, Senator Thomas Hart Benton argued, would do more good for national security than “one hundred ships of the line, ready for battle.”

The U.S. was conducting an experiment: aiming to become a mercantile power, but not a naval one. By the mid-1830s, the limitations of this policy were clear. When the country almost went to war with France in 1834, trading interests were alarmed. “It would be madness to close our eyes to the truth,” the Philadelphia Gazette said. “Our trade and our navy must have been instantly swept from the ocean by the overwhelming superiority of the French marine.”

Once again, the U.S. became sensitive to its vulnerability to foreign navies. In 1838, the captain of the USS Independence was “mortified at his own weakness” as he negotiated for release of a merchantman seized by French warships. There were also reports of British warships interfering with American vessels.

One of the most vigorous advocates for a shift in policy was a young naval officer named Matthew Maury. “With a small commerce, a small navy was required,” Maury wrote in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1840. “But now, with a commerce full-fledged, spreading her wings on every sea, a larger Navy is loudly called for.”

A Growing Power

Unfortunately the U.S. was entering a deep depression, and the Treasury was draining rapidly. Still, the country began to take its first steps toward the expansion of naval power. The USS Pennsylvania was finally launched, and several other 1812- era battleships were restored to service. Experiments with new steam-powered frigates began, and a naval academy was established. A small expedition was commissioned to explore the Pacific coast, which was not yet U.S. territory.

By the late 1840s, the U.S. had the most powerful navy in its history. This wasn’t saying much: Britain and France still had vastly larger fleets. In 1846, the tonnage of British warships under construction was triple what the U.S. had afloat. Still, national policy had reached a critical juncture. The U.S. equivocated about naval power after the War of 1812, and the ghost fleet was the result. After 1840, it never would again.

Alasdair Roberts is a professor of law and public policy at Suffolk University Law School in Boston. His book “America’s First Great Depression: Economic Crisis and Political Disorder after the Panic of 1837” was published by Cornell University Press in May. The opinions expressed are his own.

Copyright 2012 Bloomberg.

Join The Club

Join The Club