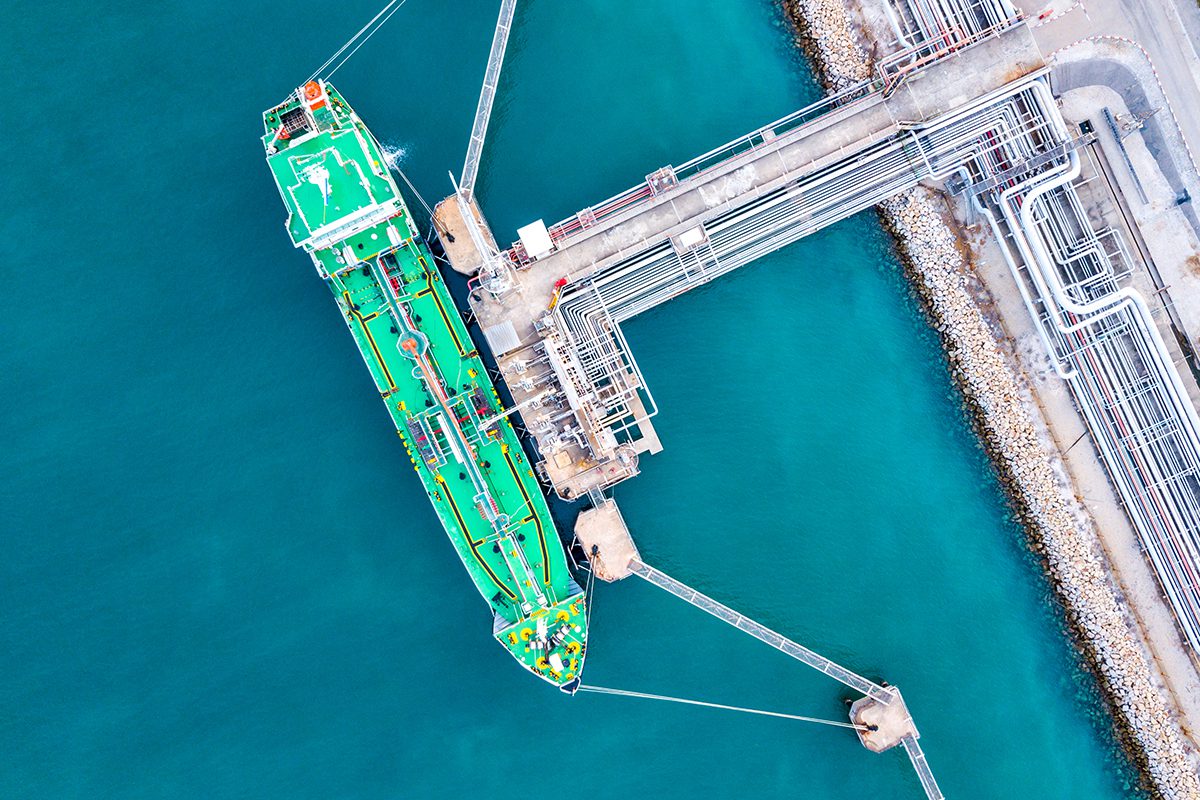

File photo shows the Horizon Spirit at the Port of Los Angeles. Photo: American Maritime Partnership

Salvatore R. Mercogliano, Ph.D. – June 5, 2020 marks the centennial of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, commonly referred to as the Jones Act. Earlier this year, I wrote an article on the passage of the act and its important to history, but with this anniversary, many opponents to the law are aiming to see its repeal and demise.

As one of the three legs on which the modern American deep-draft merchant marine resides upon – the others being the requirement for government cargo preference and the Department of Defense funded Maritime Security Program (MSP) – a loss of the Jones Act would mean the reflagging and removal of the crews from 99 of the 185 ships remaining in the fleet.

The reasons advocated for repeal are many, but they can be boiled to one salient issue: COSTS. Opponents to the Jones Act argue that American-built, American-crewed, American-owned, and American-flagged is more expensive than their foreign counterparts. To which, most normal people would respond, is that not true of nearly all other industries? And you would be largely correct. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, American ships have cost more to build and operate than their foreign counterparts. Even at the height of American industrialization and steel manufacturing, the rising standard of wage in the United States, and labor reforms made costs higher. Today, while crews on foreign flagged ships are pushing nearly 12 months on board, American crews have the backing of the US to ensure that they are largely maintaining their rotations.

If one looks at the British merchant marine, which was the largest in the world at the dawn of the twentieth century, they utilized crews from their empire to lower costs and they decreased, but did not eliminate, subsidies for all their ships. They only did this after they were the major force upon the seas. Let’s look at one of the arguments against the Jones Act.

In November 2019, Rust Buckets: How the Jones Act Undermines U.S. Shipbuilding and National Security – the author gave away the ending with the title – was published by the CATO Institute. The paper kicks it off with a study by the OECD on what the repeal would mean for the increased US economic output; they place it at $135 billion. This is what opponents do, they focus on the economics and do not discuss the national security implications.

The focus is exclusively on Section 27 of the act and state that this is the Jones Act; and that is incorrect. The entire Merchant Marine Act of 1920 was created as a comprehensive national sealift strategy. Over time, elements of it have been undermined and co-opted. The act still provides protection for American mariners – both offshore and coastal – and that is also part of the Jones Act. The genesis of the act in 1920 was to deal with the large war-built fleet of the US Shipping Board and specifically address the shortages the nation faced when it entered World War One. Specifically, it wanted to prevent an occurrence where the US would be dependent upon foreign shipping in the future – this is exactly what the opponents of the Jones Act propose by the way. But have no worries, many of them have assured me that there will never be another war in the future – “Peace in our Time?”

The paper goes on to say, “Claims that the Jones Act is a national security asset have generally gone unchallenged.” Really? There have been groups and individuals fighting the Jones Act since I started sailing in the late 1980s. He argues that the law’s restrictions make it difficult to “foster a merchant marine and shipbuilding and repair capability that can be harnessed by the United States in time of war.” There is no denying that shipbuilding capacity and the number of ships being built in the US has declined. But why?

Well first, this is an international phenomenon. Although we are at an all-time high in number of ships and tonnage, 94% of all ships are built in China, Republic of Korea, Japan, and the Philippines. The name in shipping right now is consolidation, and in those countries, yards are merging into larger ones that are “Too Big to Fail.” This means, with COVID-19 hitting, those nations are dumping money into them to prevent them from going under and undercutting each other to get more shares of the industry. If the US was not a global power, it would not matter too much where its ships are built or crewed, but with military stationed in over 150 countries world-wide and a presence in all the oceans, is it wise for the US to surrender its commercial fleet to its economic rivals.

The example that is used is the scenario of the Persian Gulf War. The statistic that, “of the 281 Ready Reserve Force (RRF) and commercial ships chartered by the Military Sealift Command during the conflict, a mere eight were Jones Act-eligible.” Well, that is wrong! He identifies the ships but fails to mention all the other ships that meet this standard. Note, he cited Jones Act-eligible. Well, eight out of the thirteen Maritime Prepositioning Ships meet that criteria; all the ships chartered from Lykes Lines also met those requirements; but that does not fit the narrative, so it is omitted. This is a long running description that should have been debunked by the Department of Defense, Military Sealift Command, the Maritime Administration or the US Transportation Command, but it continues.

One of the reasons for this is the Defense Department invested in converting and constructing new ships for its surge sealift fleet. As they focused on this, they allowed the construction and differential subsidies that kept many ships of the international trading fleet – but were built in US yards and could engage in coastal trade – to lapse as they assumed their own surge fleet could handle future sealift operations. However, they did not factor in the sustainment, which relied on the commercial merchant marine, the shuttle ships for the US Navy replenishment vessels, or the galvanizing of opposition to the Jones Act.

The report also highlights the limited ship availability and notes the use of Ponce in the sealift effort. To paraphrase the report, since only one ship was needed in the operation from the Jones Act fleet, why have the Jones Act. A recent Center for Strategic Budgetary Assessments report highlighted the critical shortage in container capacity, roll-on/roll-off space, and most importantly fuel. Operation Desert Shield/Storm was a limited war in the perspective of the United States. It was endorsed by the United Nations and therefore it had large coalition support, meaning that the US could tap into shipping of other nations. This was not the case in Vietnam for the US from 1965-73 or the British in the Falklands in 1982. In both those cases, the nations utilized their domestic fleets to support their war effort. For America, that was until it could break out ships from the reserve fleet and develop new methods of cargo handling.

Not to leave the issue completely with no hope, the author proposed three solutions. First, the piece advocated for a civilian Merchant Marine Reserve; a concept that I endorsed in an earlier piece in gCaptain. This would organize the licensed merchant mariners, but their proposal fails to identify where these mariners will train or get experience and upgrade their licenses if the Jones Act fleet is foreign flagged? Second, he is fine with subsidizing the training of mariners, but not ships, shipyards, or operators. Finally, he advocates, well let me quote him directly, “policymakers should consider allowing foreign mariners to crew chartered auxiliary commercial sealift ships.”

It is that last idea that brings us back to the why the Jones Act was passed a century ago. In April 1917, when the US declared war against Germany it had suffered economic hardship. The divergence of the British and German merchant fleets from American trade crippled the economy and led to recession and panic. The Shipping Act of 1916 aimed to promote American shipbuilding and the maritime sector. As American ships shifted from the cabotage trade (this was pre-Jones Act) they went into international shipping to fill the void left went foreign ships deserted the trade. It was those ships that Germany attacked in early 1917 that led to American entry after ten ships were sunk and 64 mariners killed.

As a show of force, the US agreed to hastily scramble together a land force and ship them to France. A total of 14 ships were chartered or commandeered from the American merchant marine – one in international trade, two in the Caribbean, and eleven were operating along the US coast. The ships delivered the Army’s First Infantry Division to France, and one of its officers exclaimed in Paris, “Lafayette We Are Here!” The Navy commander of the convoy, Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves, had some issues with merchant ships on the voyage across.

The merchant officers of the transports were, on the whole, a highly efficient and capable body of men. Of the crews, little good can be said. These men are mostly the sweepings of the docks…men of all nationalities were shipped…in one case a member of the crew of the Momus of German extraction, openly threatened the safety of the ship. The crews of these transports at all times formed a serious menace to the safety of the convoy.

While Gleaves statement may be part hyperbole, it does raise concern to a policy that would vest the national security of American sealift in the hands of foreign seamen. At the end of the war, while America shipped most of the 6 million tons of cargo, it could only muster 45% of the transport space needed to ship the two-million-person expeditionary force to France. After the war, using their leverage, the British refused to release their fleet to return the Americans home. The Canadian military learned this lesson in 2000 when they had to retake a cargo ship that refused to dock and offload a large portion of the Canadian Army’s equipment; the subject of a great podcast by CIMSEC.

In World War Two, Jones Act ships provided the underway replenishment for the fleet carriers during the critical year of 1942. At the battle of Midway, the former SS Seatrain New York, converted into USS Kittyhawk, delivered Marines and their aircraft to the island just before the Japanese attack on June 4, 1942. Vessels drawn from the merchant fleet, including many built under the Jones Act, made up the invasion fleets at Guadalcanal and North Africa later that year. It was American merchant marine that provided the link between the Arsenal of Democracy to the battlefront, across contested seas.

Is there a significant issue with the American merchant marine today…YES! But the problem does not rely with the Jones Act, but what has come before it. How has the American merchant marine gone from being not only the largest in the world, but from carrying nearly 2/3 the world’s cargo at the end of the Second World War to only a fraction of a percent of its exports and imports.

For this, I will quote Deadliest Catch’s (by the way, all those ships are Jones Act too) Mike Rowe during his National Maritime Day 2020 comments, “You guys need better PR [public relations].” I agree with Mike Rowe! At the end of the Second World War, all the service branches – Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps – had official histories written. The Navy’s is 15 volumes and the Army’s is a whopping 79 books. The War Shipping Administration, that oversaw the merchant marine, history totals 81. Not volumes, but pages. If you wrote a paragraph about each of the 733 ships sunk it would be longer, let alone the over 9,500 mariners who died.

So, the American merchant marine comes out of its greatest achievement with almost no recognition. Next, the United States initiated programs that ensured that its merchant marine would not remain on top. In 1946, it passed the Ships’ Sale Act to restock the world’s merchant fleets, including the Japanese and Germans with American ships. Economically, what a dumb move when the US was supreme, but politically, it was the maritime version of the Marshall Plan.

Before the war the US used the Panamanian registry to get around Congressional neutrality laws to ensure that Great Britain would not fall. After the war, the use of the registry as a cheaper alternative started a trend, that the US magnified with the creation of the Liberian registry. Internally in the United States, several initiatives took hold that impacted the coastal trade and the Jones Act fleet. The introduction of the interstate highway system and pipelines in the late 1950s eliminated a great deal of demand for coastal shipping. The advent of commercial airliners took passengers off the rails and freed the space for cargo.

All of these decreased the need for Jones Act shipping. Add to this the decision in the 1980s to stop constructing in Navy shipyards, and the curtailment and eventually demise of construction and operational differential subsidies for the international fleet, meant private shipyards focused on government contracts. Plus, many of those international carriers were also involved in coastal trade. When you track the decline of American shipping, these inflection points are all apparent, but it is too easy to just blame the Jones Act, since this is one of only three protections remaining.

The question that is never answered by those who oppose the Jones Act is what happens if you do repeal it. Yes, transportation costs will drop, but will Americans see benefits? First, there will the issue with foreign crews. While foreign mariners arrive in US ports every day, this will be expanded to coastal ships that frequent smaller ports and remain pier side longer. There is the issue of US labor laws – will foreign mariners work for a fraction of the cost of Americans or will that be prohibited? If they are, what does that say about the use of foreign labor in other aspects of American industry at reduced wages. If not, what is the benefit. Plus, those mariners will be signed on board for 6 to 12 months and issues with crew changes are plaguing the shipping world today.

Where will these ships be built? With China building 40 percent of the world total, is it hard to imagine that they would not want to make inroads into the United States. If it is not China, then shipyards and repair facilities would be close to them. As ships will not be required to be repaired in American shipyards, that work would go offshore, leading to the closing of more yards and repair facilities; thereby impacting the US Navy.

Finally, there is the issue of national security. The Jones Act was passed as a result of a conflict erupting in Southeast Europe that drew in the regional powers and expanded to pull in the United States. Is it far flung to imagine an incident in Southeast Asia that precipitates a war between the major shipping nations of the world today, leaving the United States in the same situation it found itself in before the Jones Act? American trade would be piling up on the docks, no material being imported, but in this scenario, there is no coastal or Jones Act fleet to draw upon, or shipyards in action due to a program started a few years prior.

The United States would find itself with a Navy that could not support its fleet because of the lack of tankers to supply oilers. It would have newly trained mariners graduating from the maritime academies, but it would lack the mid-level and senior deck and engine personnel because there were no ships for them to work on and get practical experience. The surge sealift fleet would be in further disrepair due to the lack of shipyards for service and shortages in trained mariners, meaning the Army, Air Force, and even elements of the Marine Corps would be stuck in the continental United States.

Yes, the Jones Act means it is more expensive to ship goods. Is it unfair for those in Hawaii, Alaska, and Puerto Rico? Yes, but there are solutions short of repeal? The Maritime Security Program funded by the Department of Defense provides 60 ships with a $5 million stipend per ship per year to offset costs; equal to $300 million a year. Expand the MSP to the Jones Act; zero out corporate tax rates for the handful of US shipping companies; waive federal income tax for mariners allowing companies to lower their payrolls; provide tax credits for shippers who shift their cargo off road and rail onto coastal shipping; begin a public relations program to promote the merchant marine; have the Department of Defense look at auxiliary ships for sealift capitalization and logistic support that have commercial capabilities which would lower their costs and eliminate design for commercial contractors; and most importantly, use some of that Shark Tank innovation and capital in America to bankroll new shipping firms and methods of delivery.

The United States has always been on the forefront of the maritime industry, from super tankers and the cruise industry, to containerization. It can do it again but repealing the Jones Act is an act of uncertainty that may spell short-term benefits with long-term consequences.

Salvatore R. Mercogliano is an associate professor of History at Campbell University in Buies Creek, North Carolina and teaches courses in World Maritime History and Maritime Security.

Editorial Standards · Corrections · About gCaptain

Join The Club

Join The Club