Gunvor to Ship North Sea Crude to Asia After Bull Play Wraps Up

(Bloomberg) — Gunvor Group will send a supertanker loaded with North Sea Forties crude to Asia after the trading house amassed a large volume of benchmark oil in a month-long...

A commercial freight train carries a load of shipping containers at the Port of Savannah, Georgia, U.S. October 17, 2021. REUTERS/Octavio Jones

While inbound container growth appears to be flattening for now, the long-term outlook spells trouble for U.S. ports.

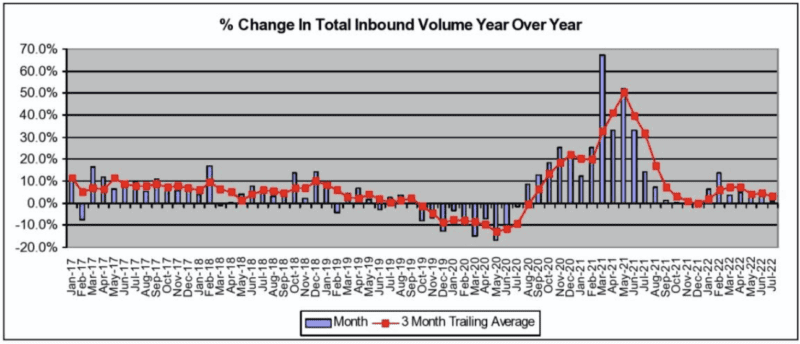

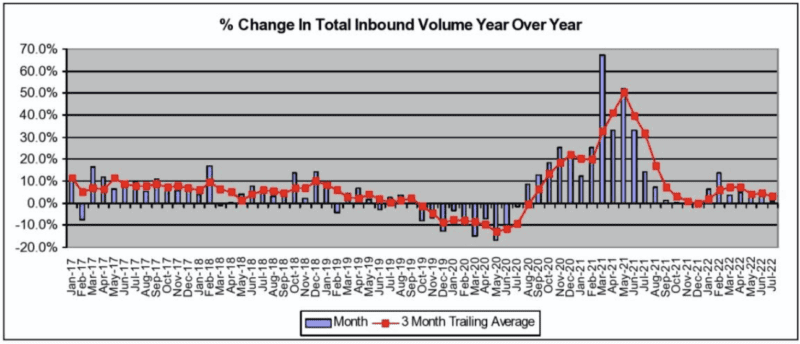

Liner industry veteran John McCown, founder of Blue Alpha Capital, is out with his July report on the top ten U.S. ports, showing another month of gains in July even as U.S. consumers’ pandemic-fueled spending is starting to cool.

McCown’s report shows the ten largest ports in the United States registered a 0.7% increase in inbound container volumes in July compared to the same month last year.

There’s been much debate about when the U.S. import growth would flatten or turn negative. The time appears to be now.

McCown’s report shows year over year gains have fallen considerably since last August following many months of double digit growth. This flattening was inevitable, considering ports are already operating at or near capacity. Looking towards the rest of the year, growth is expected to remain flat or likely turn negative during some months. This can be attributed to more difficult comparisons to last year and wider port congestion, McCown says in his report.

Speaking of congestion, McCown points out that the situation has changed more in its composition rather than total impact. While West Coast ports, particularly in Southern California, have made some progress in reducing backlogs, congestion has spread elsewhere, with places like New York, Savannah and Houston seeing high numbers of ships waiting for berths. Even smaller ports are seeing record volumes.

According to McCown, the West Coast represented two-thirds of containerships waiting for berths in January, but it now represents less than on-third as congestion has shifted eastward as ports there struggle under the weight of heightened imports (and empties, in some cases).

McCown has been talking about this West to East cargo shift for months now. Shippers and ocean carriers facing long wait times on the West Coast have shifted cargoes and capacity to East and Gulf coast ports in hopes of finding greener pastures. Meanwhile, the possiblity of challenges resulting from ongoing labor talks between West Coast dockworkers represented by the ILWU and port employers has further contributed to this shift.

“This whack-a-mole effect where relief of waiting times on the West Coast resulting from deployment changes led to moving some of that congestion to East/Gulf Coast ports is yet another example of network effects within container shipping systems that have been evident throughout the pandemic,” McCown writes.

Bigger picture… the fact that containerships are now waiting on all three U.S. coasts, particulary now during a period a flat growth, is a “tangible reminder” that many U.S. ports are operating at or near capacity and not equipped to handle foreseable future growth.

Even if the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for inbound containers comes in at a conservative 2.8%, as estimated by DNV (which is half of the 5.6% CAGR witnessed from 1995-2026), the number of inbound containers to U.S. ports will be twice as much in 25 years and four times as much in 50 years, according to McCown.

“The present U.S. port system is not in the position to accommodate the geometric growth in container volume that is on the foreseable horizon. To handle that growth, something more than just marginal improvements to capacity are needed,” McCown writes. “Among other things, new container terminals and even entirely new container ports will be needed to efficiently handle container volume over the ensuing decades. This will require significant infrastructure investment… Without meaningful steps taken, such disruption will be more episodic in the future as volume grows over time.”

According to McCown’s calculations, disruptions related to congestion is costing the U.S. economy $82 billion annually in additional container shipping costs, based on Q2 2022 numbers. While infrastructure investments may be costly, the cost of doing nothing is likely to be much, much greater.

The full report can be found here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/inbound-containers-up-07-july-john-d-mccown/

Join the gCaptain Club for curated content, insider opinions, and vibrant community discussions.

Join the 107,105 members that receive our newsletter.

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Access exclusive insights, engage in vibrant discussions, and gain perspectives from our CEO.

Sign Up

Maritime and offshore news trusted by our 107,105 members delivered daily straight to your inbox.

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Sign Up