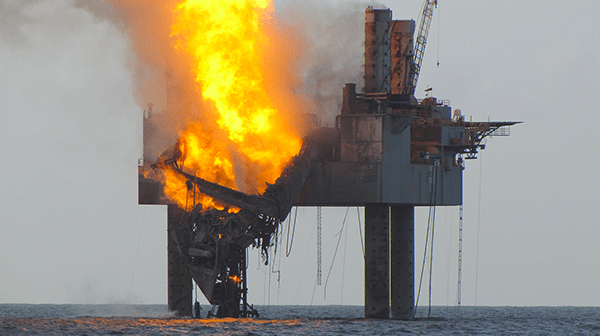

Image: BSEE

An anonymous gCaptain source gave us the second-hand run down of what transpired on board the Hercules 265 when at 0845 on July 23, well A-3 blew out at South Timbalier 220, forcing the evacuation of the rig, and leading to a catastrophic well fire 14 hours later.

The scenario

The rig crew had been conducting completion work on the sidetrack well to prepare it for production. A sidetrack well is a well that starts as part of a previously existing wellbore, but ends up getting diverted sideways through the existing casing and wellbore in order to allow the drill to enter a different formation.

Before the incident, the rig crew had “spotted a pill” at the perforation zone. Meaning, a special chemical mixture had been pumped down the drill string and into the well bore at the location of the perforation (the area where explosives were used to blast through the casing and cement in order to expose the hydrocarbon-bearing formation.)

The pill had was circulated with a lighter weight completion fluid and when it reached the perforation zone, the driller monitored the well for any changes. None were noticed.

After monitoring the well, the rig crew then began retrieving the drill string out of the wellbore, aka, tripping out of the hole.

While tripping out of the hole, the driller must be careful to not retrieve the pipe too quickly because the drill pipe can act like a giant syringe, depressurizing the wellbore and causing a kick, or an influx of gas or hydrocarbons into the well. In addition, the volume of space that is occupied by the drill string must be continuously pumped back into the well as the pipe is retrieved, otherwise the carefully balanced hydrostatic pressure at the bottom of the hole will be reduced, causing a kick or ingress of formation fluids.

Our source notes that “proper fill-ups” had been taken during the entire tripping process, which reflected a static, non-flowing well condition.

With 9 stands of 3 1/2″ drillpipe, plus the bottom hole assembly, hanging from the top drive, high density completion fluid began pouring out through the rotary table.

At that point in time, the driller had two stands raised above the rotary table which he then quickly lowered back down into the hole.

The driller then closed the diverter, which sealed off the area between the inside diameter of the rotary table and the outside diameter of the drill pipe, forcing the upwards-flowing gas and fluids to exit over the side of the rig via a large diverter manifold.

Once the top of the drill pipe was at deck level, the roughnecks were required to act fast and secure a TIW valve (very heavy duty ball valve) to the top of the drill string, effectively blanking it off.

Unfortunately, the blowout came too quickly, overpowering the diverter, and launching the pipe skyward into the derrick.

Considering the roughnecks were in the process of affixing the TIW valve to the drill pipe, it seems unlikely that the shear rams of the Blow Out Preventer (BOP) had been activated when the drillpipe flew up into the derrick because once the shear rams are activated, there would have been no need for a TIW valve.

Our source confirms however, that the driller did actuate the BOP, but with a negative result, possibly due to the lack of weight in the drill string. (With only 9 stands of pipe, plus BHA, there may not have been enough tension on the pipe to help the cutting surfaces of the BOP slice through the material)

With no other options left to control the well, the rig crew immediately evacuated.

How this may have occurred

Considering the driller had proper fillups during the entire tripping process, and the event happened so quickly, this situation seems a bit unusual. If the kick had happened far down the hole, the fillups would not have been consistent during the tripping process because as the gas migrated up the wellbore, the gas would have expanded, raising the level of the wellbore fluids.

That would have likely been noticeable.

Our source believes that part of the well’s steel casing liners may have failed near the top because had the gas bubble migrated outside the wellbore along the steel casing, and then entered the wellbore somewhere closer to surface, the blowout may not have been noticed until it was too late.

Without further details on the situation, it’s impossible to say exactly what happened, but our source adds that,

“But by no means was it the rig hands fault.”

Here’s what I think:

When the driller lowered the string to deck level after noticing that a kick was coming, he immediately closed the diverter and was likely in the process of closing the pipe rams (which would seal around the pipe, but not cut the pipe) when the gas bubble hit the surface and blew out the well. The roughnecks didn’t have time to stab in the TIW valve and for one reason or another, the blind shear rams failed to cut the pipe after the blowout occurred.

It will be interesting to get more information about the fill-ups that were taken during the tripping process, how often they were taken, and how closely the well was being monitored during the trip.

Read more: How a Jack-Up Rig Blowout Occurs

Unlock Exclusive Insights Today!

Join the gCaptain Club for curated content, insider opinions, and vibrant community discussions.

Join The Club

Join The Club